The Cripple Creek Miners' Strike of 1894 was a five-month strike by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) in Cripple Creek, Colorado. It resulted in a victory for the union. It is notable for being the only time in U.S. history when a state militia was called out in support of striking workers. The strike was characterized by firefights and the use of dynamite, and ended after a standoff between the Colorado State Militia and a private force working for owners of the mines. In the years after the strike, the WFM's popularity and power increased significantly throughout the region.

Background

At the end of the nineteenth century, Cripple Creek, with a population of about 15,000, was the second-largest town in Colorado. Along with the towns of Altman, Anaconda, Arequa, Goldfield, Elkton, Independence, and Victor, Cripple Creek lay in a deep valley about 20 miles from Colorado Springs on the southwest side of Pikes Peak. Surface gold was discovered in the area in 1891, and within three years, more than 150 mines were operating there. In 1893, the economic downturn, known as the Panic of 1893, caused the price of silver to crash. Gold prices, however, remained high, and gold was in fact desperately needed to replenish federal reserves. The influx of silver miners into the gold mines caused a lowering of wages. Mine owners demanded longer hours for less pay, and assigned miners to riskier work.

In January 1894, Cripple Creek mine owners J.J. Hagerman, David Moffat, and Eben Smith, who together employed one-third of the area's miners, announced a lengthening of the work day to ten hours (from eight), with no change to the daily wage of $3.00 per day. When workers protested, the owners agreed to employ the miners for 8 hours a day, but at a wage of only $2.50.

Not long before this dispute, miners at Cripple Creek had formed the Free Coinage Union. Once the new changes went into effect, they affiliated with the Western Federation of Miners, and became Local 19. On February 1, 1894, the mine owners began implementing the 10-hour day. Union president John Calderwood issued a notice a week later demanding that the mine owners reinstate the eight-hour day at the $3.00 wage.

The Strike

When the owners did not respond, the nascent union struck on February 7. Portland, Pikes Peak, Gold Dollar, and a few smaller mines immediately agreed to the eight-hour day and remained open, but larger mines held out.

The strike had an immediate effect. By the end of February, every smelter in Colorado was either closed or running part time. At the beginning of March, the Gold King and Granite mines gave in and resumed the eight-hour day. Mine owners still holding out for the 10-hour day soon attempted to reopen their mines. On March 14, they obtained a court injunction ordering the miners not to interfere with the operation of their mines, and brought in a small number of strikebreakers. The WFM initially attempted to persuade these men to join the union and strike, but when they were unsuccessful, the union resorted to threats and violence, succeeding in keeping the many non-union miners away.

The conflict escalated, as the mine owners recruited ex-police and ex-firefighters to form a private army, and miners resorted to dynamite and armed conflict. In a development unparalleled in American labor history, Colorado Governor Davis H. Waite declared the mine owners' force of 1,200 deputies to be illegal and ordered the group disbanded on May 28. However, this army of deputies, organized by Sheriff Bowers, eventually got out of control, and state militia was again called in—this time to protect the miners and civilians of the town, and threatening to declare martial law. The deputies finally disbanded on June 11. The Waite agreement, providing for the resumption of the $3.00-per-day wage and the eight-hour day, became operative the same day, and the miners returned to work. Union president Calderwood and 300 other miners were arrested and charged with a variety of crimes. Only four miners were convicted of any charges, and they were quickly pardoned by the sympathetic populist governor.

The Cripple Creek strike was a major victory for the miners' union. The Western Federation of Miners used the success of the strike to organize almost every worker in the Cripple Creek region—including waitresses, laundry workers, bartenders, and newsboys—into 54 local unions. The WFM flourished in the Cripple Creek area for almost a decade, even helping to elect most county officials, including the new sheriff.

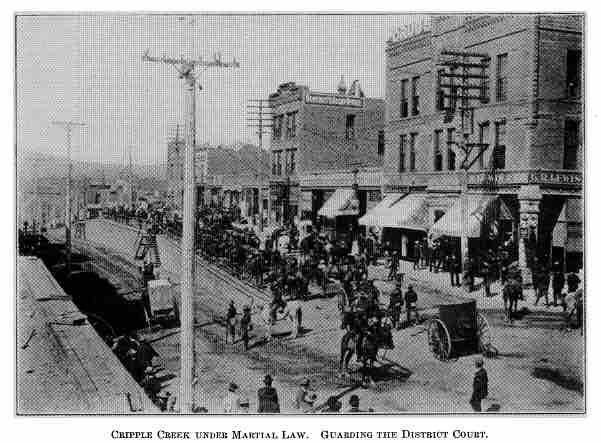

"Cripple Creek Under Martial Law"

This photo shows Cripple Creek under martial law in 1894.