Background

The issue of personal character was paramount in the 1884 presidential campaign. Former Speaker of the House James G. Blaine had been prevented from getting the Republican presidential nomination during the previous two elections because of the stigma of the "Mulligan letters." In 1876, a Boston bookkeeper named James Mulligan had located some letters showing that Blaine had sold his influence in Congress to various businesses. One such letter ended with the phrase, "burn this letter," from which a popular chant of the Democrats arose: "Burn, burn, burn this letter!" In just one deal, Blaine had received $110,150 (more than $1.5 million in 2010 dollars) from the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad for securing a federal land grant, among other things. Democrats and anti-Blaine Republicans made unrestrained attacks on his integrity as a result.

New York Governor Grover Cleveland, on the other hand, was known as "Grover the Good" for his personal integrity. In the space of the three previous years, he successively had become the mayor of Buffalo and then the governor of the state of New York, cleaning up large amounts of Tammany Hall's corrupt political machinery.

It came as a tremendous shock when, on July 21, the Buffalo Evening Telegraph reported that Cleveland had fathered a child out of wedlock, that the child had gone to an orphanage, and that the mother had been driven into an asylum. Cleveland's campaign decided that candor was the best approach to this scandal: They admitted that Cleveland had formed an "illicit connection" with the mother and that a child had been born and given the Cleveland surname. They also noted that there was no proof that Cleveland was the father, and claimed that, by assuming responsibility and finding a home for the child, he was merely doing his duty. Finally, they showed that the mother had not been forced into an asylum. Her whereabouts were unknown.

Cleveland Gains Support

The Democrats held their convention in Chicago the following month and nominated Governor Grover Cleveland of New York. Cleveland's time on the national scene was brief, but Democrats hoped that his reputation as a reformer and an opponent of corruption would attract Republicans dissatisfied with Blaine and his reputation for scandal. They were correct, as reform-minded Mugwump Republicans denounced Blaine as corrupt and flocked to Cleveland. The Mugwumps, including such men as Carl Schurz and Henry Ward Beecher, were more concerned with morality than with party politics, and felt Cleveland was a kindred soul who would promote civil service reform and fight for efficiency in government. However, even as the Democrats gained support from the Mugwumps, they lost some blue-collar workers to the Greenback-Labor party, led by Benjamin F. Butler, Blaine's antagonist from their early days in the House.

After the election, the term "Mugwump" survived for more than a decade as an epithet for a party bolter in American politics. Many Mugwumps became Democrats or remained Independents; most continued to support reform well into the twentieth century.

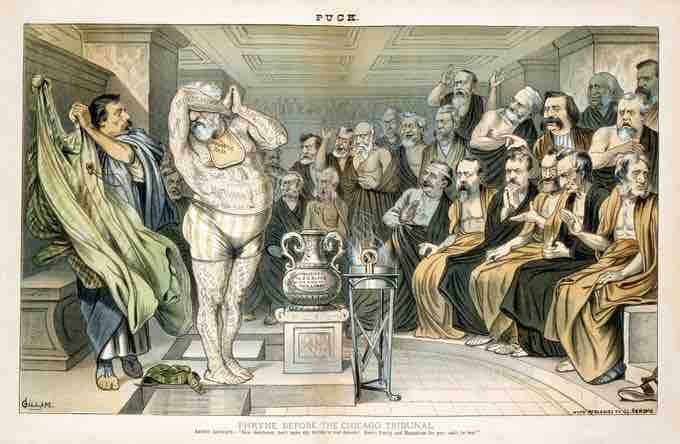

Bernard Gilliam's "Phryne before the Chicago Tribunal"

This 1884 cartoon in Puck magazine ridicules Blaine as the tattooed man, with many indelible scandals. The cartoon image is a parody of Phryne before the Areopagus, an 1861 painting by French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme.

The Election

Both candidates believed that the states of New York, New Jersey, Indiana, and Connecticut would determine the election. In New York, Blaine received less support than he anticipated when Arthur and Conkling, still powerful in the New York Republican party, failed to actively campaign for him. Blaine hoped that he would have more support from Irish Americans than Republicans typically did. While the Irish were mainly a Democratic constituency in the nineteenth century, Blaine's mother was Irish Catholic, and he believed his career-long opposition to the British government would resonate with the Irish. Blaine's hope for Irish defections to the Republican standard were dashed late in the campaign when one of his supporters, Samuel D. Burchard, gave a speech denouncing the Democrats as the party of "Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion." The Democrats spread the word of this insult in the days before the election, and Cleveland narrowly won all four of the swing states, including New York by slightly more than 1,000 votes. While the popular vote total was close, with Cleveland winning by just one-quarter of a percent, the electoral votes gave Cleveland a majority of 219 to 182.

Cleveland's Presidency

Soon after taking office, President Grover Cleveland was faced with filling all of the government jobs for which the president had the power of appointment. These jobs were typically filled under the spoils system, but Cleveland announced that he would not fire any Republican who was doing his job well. Nor would he appoint anyone solely on the basis of party service. Cleveland also used his appointment powers to reduce the number of federal employees, as many departments had become bloated with political timeservers.

Later in his term, Cleveland replaced more of the partisan Republican officeholders with Democrats. While some of his decisions were influenced by party concerns, more of Cleveland's appointments were decided by merit alone. Cleveland also reformed other parts of the government. In 1887, he signed an act creating the Interstate Commerce Commission. He also modernized the navy and canceled construction contracts that had resulted in inferior ships. Cleveland angered railroad investors by ordering an investigation of western lands they held by government grant.

Cleveland and Tariff Reform

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the "McKinley Tariff," was an act of the U.S. Congress framed by Representative William McKinley that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost fifty percent, an act designed to protect domestic industries from foreign competition. Protectionism, a tactic supported by Republicans, was fiercely debated by politicians and condemned by Democrats.

The tariff was not well received by Americans, who suffered a steep increase in the cost of products. In the 1890 election, Republicans House seats went from 166 to only 88. McKinley, the act's framer and defender, was then assassinated. In the 1892 presidential election, Harrison was soundly defeated by Grover Cleveland, and the Senate, House, and presidency were all under Democratic control. Lawmakers immediately started drafting new tariff legislation.

Cleveland's opinion on the tariff was that of most Democrats: The tariff ought to be reduced. American tariffs had been high since the Civil War, and by the 1880s, the tariff brought in so much revenue that the government was running a surplus. After reversing the Harrison administration's silver policy, Cleveland sought next to reverse the effects of the McKinley tariff. What would become the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act was introduced by West Virginian Representative William L. Wilson in December 1893. After lengthy debate, the bill passed the House by a considerable margin. The bill proposed moderate downward revisions in the tariff, especially on raw materials. The shortfall in revenue was to be made up by an income tax of 2 percent on income above $4,000, ($103,000 U.S. dollars in present terms).

The bill was next considered in the Senate, where opposition was stronger. Cleveland faced opposition from key Democrats, led by Arthur Pue Gorman of Maryland, who insisted on more protection for their states' industries than the Wilson bill allowed. Some voted partly out of a personal enmity toward Cleveland. By the time the bill passed the Senate, it had more than 600 amendments attached that nullified most of the reforms. The Sugar Trust in particular lobbied for changes that favored change at the expense of the consumer. Cleveland was outraged with the final bill, and denounced it as a disgraceful product of the control of the Senate by trusts and business interests. Even so, he believed it was an improvement over the McKinley tariff and allowed it to become law without his signature.