Overview

The Spanish-American War was a conflict in 1898 between Spain and the United States. It was the result of American intervention in the ongoing Cuban War of Independence. American attacks on Spain's Pacific possessions led to U.S. involvement in the Philippine Revolution and ultimately to the Philippine-American War.

Background

Revolts against Spanish rule had been endemic for decades in Cuba and were closely watched by Americans. With the abolition of slavery in 1886, former slaves joined the ranks of farmers and the urban working class, many wealthy Cubans lost their property, and the number of sugar mills declined. Only companies and the most powerful plantation owners remained in business, and during this period, U.S. financial capital began flowing into the country. Although it remained Spanish territory politically, Cuba started to depend on the United States economically. Coincidentally, around the same time, Cuba saw the rise of labor movements.

Following his second deportation to Spain in 1878, revolutionary José Martí moved to the United States in 1881. There he mobilized the support of the Cuban exile community, especially in southern Florida. He aimed for a revolution and independence from Spain, but also lobbied against the U.S. annexation of Cuba, which some American and Cuban politicians desired.

By 1897–1898, American public opinion grew angrier at reports of Spanish atrocities in Cuba. After the mysterious sinking of the American battleship Maine in Havana harbor, political pressures from the Democratic Party pushed the administration of Republican President William McKinley into a war he had wished to avoid. Compromise proved impossible, resulting in the United States sending an ultimatum to Spain that demanded it immediately surrender control of Cuba, which the Spanish rejected. First Madrid, then Washington, formally declared war.

The War

Although the main issue was Cuban independence, the 10-week war was fought in both the Caribbean and the Pacific. American naval power proved decisive, allowing U.S. expeditionary forces to disembark in Cuba against a Spanish garrison already reeling from nationwide insurgent attacks and wasted by yellow fever.

The Spanish-American War was swift and decisive. During the war's three-month duration, not a single American reverse of any importance occurred. A week after the declaration of war, Commodore George Dewey of the six-warship Asiatic Squadron (then based at Hong Kong) steamed his fleet to the Philippines. Dewey caught the entire Spanish armada at anchor in Manila Bay and destroyed it without losing an American life.

Cuban, Philippine, and American forces obtained the surrender of Santiago de Cuba and Manila as a result of their numerical superiority in most of the battles and despite the good performance of some Spanish infantry units and spirited defenses in places such as San Juan Hill. Madrid sued for peace after two obsolete Spanish squadrons were sunk in Santiago de Cuba and Manila Bay. A third more modern fleet was recalled home to protect the Spanish coasts.

The Treaty of Paris

The result of the war was the 1898 Treaty of Paris, negotiated on terms favorable to the United States. It allowed temporary American control of Cuba and indefinite colonial authority over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines following their purchase from Spain. The defeat and collapse of the Spanish Empire was a profound shock to Spain's national psyche, and provoked a movement of thoroughgoing philosophical and artistic reevaluation of Spanish society known as the "Generation of '98." The victor gained several island possessions spanning the globe, which caused a rancorous new debate over the wisdom of expansionism.

Legacy of the War

The war marked American entry into world affairs. Before the Spanish-American War, the United States was characterized by isolationism, an approach to foreign policy that asserts that a nation's interests are best served by keeping the affairs of other countries at a distance. Since the Spanish-American War, the United States has had a significant hand in various conflicts around the world, and has entered many treaties and agreements. The Panic of 1893 was over by this point, and the United States entered a long and prosperous period of economic and population growth and technological innovation that lasted through the 1920s. The war redefined national identity, served as a solution of sorts to the social divisions plaguing the American mind, and provided a model for all future news reporting.

The war also effectively ended the Spanish Empire. Spain had been declining as an imperial power since the early nineteenth century as a result of Napoleon's invasion. The loss of Cuba caused a national trauma because of the affinity of peninsular Spaniards with Cuba, which was seen as another province of Spain rather than as a colony. Spain retained only a handful of overseas holdings: Spanish West Africa, Spanish Guinea, Spanish Sahara, Spanish Morocco, and the Canary Islands.

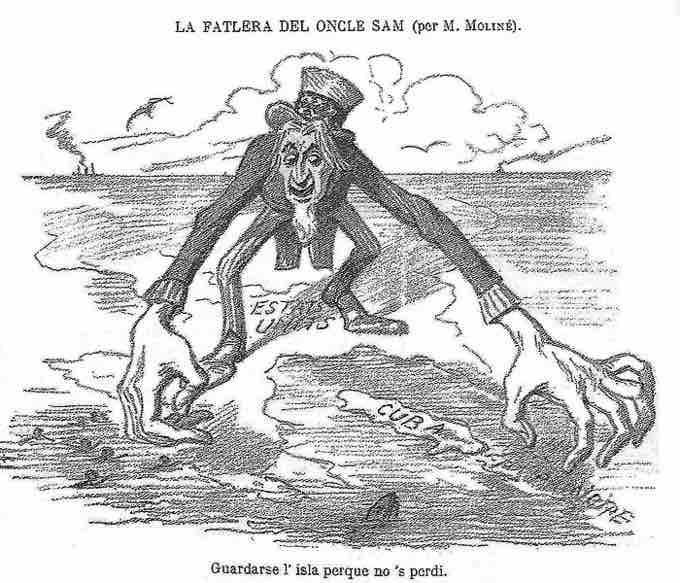

"La Fatlera del Oncle Sam"

A Catalan satirical drawing, published in La Campana de Gràcia (1896), criticizing U.S. behavior regarding Cuba.