Overview

The Watergate scandal encompasses a series of clandestine, and often illegal, activities undertaken by members of the Republican Nixon administration. Those activities included bugging the offices of political opponents and people of whom Nixon or his officials were suspicious. Nixon and his close aides also ordered harassment of activist groups and political figures, using the FBI, CIA, and the IRS to further their cause.

Despite attempts at secrecy, the activities were exposed after five men were caught breaking into Democratic party headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. on June 17, 1972. The Washington Post picked up on the story and, with tips from an FBI informant, gradually exposed the link between the burglary and the Nixon administration. Nixon downplayed the scandal as mere politics, calling news articles biased and misleading. As a series of revelations made it clear that Nixon aides had committed crimes in attempts to sabotage the Democrats and others, senior aides such as White House Counsel John Dean and Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman faced prosecution.

Facts About the Case

In January of 1972, G. Gordon Liddy, general counsel to the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP), presented a campaign intelligence plan to CRP's Acting Chairman Jeb Stuart Magruder, Attorney General John Mitchell, and Presidential Counsel John Dean, that involved extensive illegal activities against the Democratic Party. Liddy was put in charge of the operation, assisted by former CIA Agent E. Howard Hunt and CRP Security Coordinator James McCord. John Mitchell resigned as Attorney General to become chairman of CRP.

After two attempts to break into the Watergate Complex failed, on May 17, Liddy's team placed wiretaps on the telephones of Lawrence O'Brien, the Chairman of the Democratic Convention, and R. Spencer Oliver, Jr., the Chairman of the Executive Director of Democratic States. When Magruder and Mitchell read transcripts from the wiretaps, they deemed the information inadequate and ordered another break-in.

Watergate Arrests

Shortly after 1:00 am on June 17, 1972, Frank Wills, a security guard at the Watergate Complex, noticed tape covering the latch on several doors in the complex, allowing the doors to close but remain unlocked. He removed the tape and thought little of it. He returned an hour later and, having discovered that someone had retaped the locks, called the police.

Five men were discovered and arrested inside the Democratic National Convention's office. Virgilio González, Bernard Barker, James W. McCord, Jr., Eugenio Martínez, and Frank Sturgis were charged with attempted burglary and attempted interception of telephone and other communications. On September 15, a grand jury indicted them, as well as Hunt and Liddy, for conspiracy, burglary, and violation of federal wiretapping laws. The five burglars who broke into the office were tried by Judge John Sirica and convicted on January 30, 1973.

Breaking of the Watergate Story

Hearing of the incident at the Watergate complex, the Washington Post started publishing a series of articles probing the link between the burglary and the Nixon administration. Reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward relied on an informant, famously known as "Deep Throat" (later revealed to be deputy director of the FBI, William Mark Felt), to link the burglars to the Nixon administration.

On September 29, 1972, it was revealed that John Mitchell, while serving as Attorney General, controlled a secret Republican fund used to finance intelligence-gathering against the Democrats. On October 10, the FBI reported that the Watergate break-in was only part of a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage on behalf of the Nixon reelection committee. Despite these revelations, Nixon's campaign was never seriously jeopardized, and on November 7, the President was re-elected in one of the biggest landslide victories in American political history.

The connection between the break-in and the reelection committee continued to be highlighted by media coverage—in particular by The Washington Post, TIME, and The New York Times. The coverage dramatically increased publicity and consequent political repercussions. Relying heavily upon anonymous sources, Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered information suggesting knowledge of the break-in and attempts to cover it up, leading deep into the Justice Department, the FBI, the CIA, and the White House.

Watergate Apartment Complex, Washington D.C.

Despite his substantial lead in the polls, President Nixon was paranoid enough on the cusp of the 1972 election to authorize a burglary of Democratic National Committee Headquarters at the Watergate Apartment Complex on May 28th and June 17th.

Nixon's Impeachment and Resignation

As the investigation unfolded, the depths to which Nixon and his advisers had sunk became clear. Some twenty-five of Nixon’s aides were indicted for criminal activity. In July of 1973, White House aide Alexander Butterfield testified that Nixon had a secret taping system that recorded his conversations and phone calls in the Oval Office. The President’s most intimate conversations had been caught on tape, and they were subpoenaed by the Senate. Nixon refused to hand the tapes over and cited executive privilege, the right of the president to refuse certain subpoenas. On October 20, 1973, in an event that became known as the Saturday Night Massacre, Nixon ordered Attorney General Richardson to fire the prosecutor of the case, Archibald Cox. Richardson refused and resigned, as did Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus when confronted with the same order. Control of the Justice Department then fell to Solicitor General Robert Bork, who complied with Nixon’s order. In December, the House Judiciary Committee began its own investigation to determine whether there was enough evidence of wrongdoing to impeach the president.

The public was enraged by Nixon’s actions, as it seemed the president had placed himself above the law. Telegrams flooded the White House, and the House of Representatives began to discuss impeachment. At first, though Nixon lost much popular support, even from his own party, he rejected accusations of wrongdoing and vowed to stay in office. At the end of its hearings, in July 1974, the House Judiciary Committee voted to impeach. Before the full House could vote, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered Nixon to release the actual tapes of his conversations; one of the released tapes revealed that Nixon had in fact been told about White House involvement in the Watergate break-in shortly after it occurred. In a speech on August 5, 1974, Nixon, pleading a poor memory, accepted blame for the Watergate scandal. Warned by other Republicans that he would be found guilty by the Senate and removed from office, he resigned the presidency on August 8.

Nixon’s resignation, which took effect the next day, did not make the Watergate scandal vanish. Instead, it fed a growing suspicion of government felt by many. The events of Vietnam had already showed that the government could not be trusted to protect the interests of the people or tell them the truth. For many, Watergate confirmed these beliefs, and the suffix “-gate” attached to a word has since come to mean a political scandal.

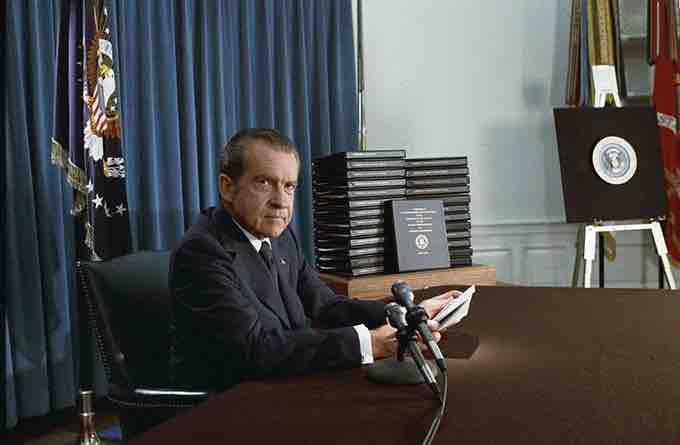

Nixon and Transcripts

President Nixon, with edited transcripts of Nixon White House Tape conversations during broadcast of his address to the Nation (April 29, 1974).