President Nixon's his most significant accomplishments were arguably in the field of foreign policy. Nixon formed what became known as the Nixon Doctrine, an approach to the Cold War in which the United States would continue to assist its allies but would not assume the responsibility of defending the entire non-communist world. Within this, his biggest achievements were in diplomacy with China and the Soviet Union.

The Nixon Doctrine

The Nixon Doctrine (also known as the Guam Doctrine) was first issued by Nixon in a press conference in Guam on July 25, 1969. Nixon stated that while the United States would continue to offer military and other support to its allies, it would henceforth expect its allies to take the lead in their own military defense, and that, in lieu of direct military action, the U.S. would also provide economic aid and military supplies. Nixon laid out the Doctrine's tenants in an address to the nation on November 3, 1969:

- First, the United States would keep all of its treaty commitments.

- Second, they would provide a shield if a nuclear power threatened the freedom of an allied nation or a nation "whose survival we consider vital to our security."

- Third, in cases involving other types of aggression, the U.S. would furnish military and economic assistance when requested in accordance with its treaty commitments; however, the nation directly threatened would assume the primary responsibility of providing the manpower for its own defense.

During Nixon's presidency, an end to direct military involvement in the Vietnam War was demanded by a majority of Americans: a poll in May showed 56% of the public believed sending troops to Vietnam was a mistake. Public opinion favored withdrawal from Vietnam, even if it meant abandonment of its treaties and a communist takeover of South Vietnam. U.S. retreat from a strategy of military intervention on behalf of Cold War allies was also driven by financial concerns and the growing expense of maintaining the war.

The Nixon administration also applied the Nixon Doctrine to conflicts in the Persian Gulf region, giving military aid to Iran and Saudi Arabia. According to author Michael Klare, application of the Nixon Doctrine "opened the floodgates" of U.S. military aid to allies in the Persian Gulf, setting the stage for the Carter Doctrine in 1980.

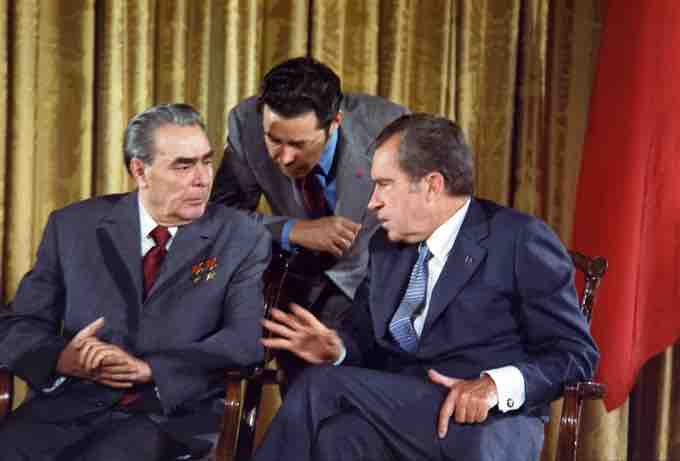

Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev and President Nixon (with a translator), 1973

Nixon met with Soviet leader Brezhnev during the latter's visit to the United States in 1973.

Vietnam

The Paris Peace Accords

The Paris Peace Accords of 1973 intended to establish peace in Vietnam and end the Vietnam War. They ended direct U.S. military involvement and temporarily stopped the fighting between North and South Vietnam. The governments of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), and the United States, as well as the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) that represented indigenous South Vietnamese revolutionaries, signed the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam on January 27, 1973. The agreement was not ratified by the U.S. Senate. In March of 1973, Nixon implied that the United States would intervene militarily if the communist side violated the ceasefire; however on June 4, 1973, the U.S. Senate passed the Case-Church Amendment to prohibit such intervention.

Renewed Conflict and the Fall of South Vietnam

After the withdrawal of American forces, it was not long before renewed conflict ignited between North Vietnam and South Vietnam. The Vietcong resumed offensive operations when dry season began, and by January of 1974 it had recaptured the territory it lost during the previous dry season. After two clashes that left 55 South Vietnamese soldiers dead, President Thiệu announced on January 4, 1974, that the war had restarted and that the Paris Peace Accord was no longer in effect. There had been over 25,000 South Vietnamese casualties during the ceasefire period.

On April 30, 1975, North Vietnamese troops overcame all resistance and took Saigon. Following the North Vietnamese takeover of South Vietnam, a reunited Vietnam subsequently invaded the Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia) during the Cambodian-Vietnamese War and fought the Third Indochina War, or the Sino-Vietnamese War, against a Chinese invasion. Amidst the violence in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand, more than 3 million people fled the region, eventually finding their way to the United States, Canada, Australia, and France after being refused by many Asian countries.

Effects of the War on the U.S.

Between 1965 and 1975, the United States spent 686 billion, resulting in a large federal budget deficit. More than 3 million Americans served in the Vietnam War; by war's end, 58,220 American soldiers had been killed, more than 150,000 had been wounded, and at least 21,000 had been permanently disabled. In 1977, United States President Jimmy Carter granted a full, complete, and unconditional pardon to all Vietnam-era draft dodgers. Large death tolls amongst American soldiers, including many under the age of 21, combined with large numbers of desertions and draft dodging led to drastic changes in the U.S. military, including the end of conscription. In addition to human losses and financial deficit, U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War demonstrated to many in the U.S. that there were limitations to its overseas military engagements.

Latin America

The Nixon administration pursued American's strategic interests in conflicts in Latin America. Nixon had been a firm supporter of Kennedy in the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Upon taking office, Nixon increased covert operations against communist Cuba and its president, Fidel Castro. These activities worried the Soviets and Cubans, who feared Nixon might attack Cuba, in violation of the 1962 agreement which had ended the missile crisis. Meanwhile, U.S. intelligence revealed that the Soviet Union was expanding their base at the Cuban port of Cienfuegos in October of 1970. A minor confrontation ensued, which was concluded with an understanding that the Soviets would not use Cienfuegos for submarines bearing ballistic missiles. The final round of diplomatic notes, reaffirming the 1962 accord, were exchanged in November.

In September of 1970, the election of Marxist candidate Salvador Allende as President of Chile led Nixon to order that Allende not be allowed to take office. Edward Korry, U.S. Ambassador to Chile, told Nixon that he saw no alternative to Allende, and Nixon ruled out American intervention, though he remained willing to assist opponents of Allende who might come forward. The military regrouped under General Augusto Pinochet, who overthrew Allende in 1973 with the backing of the United States. During the coup, the deposed president died under disputed circumstances. There have been allegations of CIA involvement in the coup, incited by declassified transcripts of conversations between Nixon and his National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger.

The Middle East

The Nixon administration strongly supported Israel, an American ally in the Middle East, although the support was not unconditional. Nixon believed that Israel should make peace with its Palestinian Arab neighbors and that the United States should encourage this. The president believed that—except during the Suez Crisis—the U.S. had failed to put sufficient pressure on Israel to do its part in the conflict resolution process. Nixon believed that the U.S. should use it massive military aid contributions to Israel as leverage in bringing all parties to the negotiating table. However, the Arab-Israeli conflict was not a major focus of Nixon's attention during his first term—for one thing, he felt that no matter what he did, American Jews would oppose his reelection, and much of his efforts during his first term were geared toward ensuring his reelection.

In October of 1973, an Arab coalition led by Egypt and Syria attacked Israel, beginning the Yom Kippur War. Israel suffered initial losses but had cut deep into foreign territory by the time the U.S. and Soviet Union had negotiated a truce. After taking no action at the beginning of the war, Nixon cut through inter-departmental squabbles and bureaucracy to initiate an airlift of American arms. The war resulted in the 1973 oil crisis, in which Arab nations refused to sell crude oil to the U.S. in retaliation for its support of Israel.

The Energy Crisis

In October of 1973, the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries, or the OAPEC, proclaimed an oil embargo "in response to the U.S. decision to re-supply the Israeli military" during the Yom Kippur War; it lasted until March of 1974. OAPEC declared it would limit or stop oil shipments to the United States and other countries if they supported Israel in the conflict.

With the U.S. actions seen as initiating the oil embargo, the long-term possibility of embargo-related high oil prices—along with the disrupted supply and the resulting recession—created a strong rift within NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, an alliance of countries from Europe and North America), and European countries and Japan sought to disassociate themselves from the U.S. Middle East policy. Arab oil producers had also linked the end of the embargo with successful U.S. efforts to create peace in the Middle East, which complicated the situation. To address these developments, the Nixon Administration began parallel negotiations with both Arab oil producers to end the embargo, and with Egypt, Syria, and Israel to arrange an Israeli pull-back of military forces. By January 18, 1974, Kissinger had negotiated an Israeli troop withdrawal from parts of the Sinai. The promise of a negotiated settlement between Israel and Syria was sufficient to convince Arab oil producers to lift the embargo in March of 1974. By May, Israel agreed to withdraw from the Golan Heights.

The effects of the embargo were immediate, and the price of oil quadrupled by 1974. This had a dramatic effect on oil-exporting nations, as the countries of the Middle East, which had long been dominated by the major industrial powers of the world, were seen to have acquired control of a vital commodity. The traditional flow of capital reversed as the oil-exporting nations accumulated more wealth. The Arab embargo had a negative impact on the U.S. economy, causing immediate demands to address the threats to U.S. energy security and search for new ways to develop expensive oil. The retail price of a gallon of gasoline (petrol) rose from a national average of 38.5 cents in May 1973 to 55.1 cents in June 1974. State governments requested citizens not put up Christmas lights, with Oregon banning commercial lighting altogether. Politicians called for a national gas rationing program. The of the energy crisis lingered on throughout the 1970s, amid the weakening competitive position of the dollar in world markets.

Shuttle Diplomacy

In diplomacy and international relations, shuttle diplomacy is the action of a third party in serving as an intermediary between principals in a dispute, without direct principal-to-principal contact. Originally and usually, the process entails successive travel ("shuttling") by the intermediary, from the working location of one principal to that of another. The term was first applied to describe the efforts of United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, beginning November 5, 1973, which facilitated the cessation of hostilities following the Yom Kippur War. Negotiators often use shuttle diplomacy when one or both of the two principals refuses to recognize the other.

Shuttle diplomacy became an important part of Kissinger's diplomatic efforts in the Middle East during the Nixon and Ford administrations. He accomplished the Sinai Interim Agreement (1975) and arrangements between Israel and Syria on the Golan Heights (1974). Kissinger also oversaw United States negotiations in Vietnam in the 1960's, playing a leading role in the negotiations that produced the Paris Peace Accords. Under Kissinger's influence, the United States government supported Pakistan in the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971. Kissinger was particularly concerned about the expansion of Soviet influence in South Asia as a result of a treaty of friendship recently signed by India and the U.S.S.R., and he sought to demonstrate to the People's Republic of China (Pakistan's ally and an enemy of both India and the Soviet Union) the value of a tacit alliance with the United States.