Colonial Resistance Strategies

Following the Molasses, Sugar, and Quartering Acts, Parliament passed one of the most infamous pieces of legislation: the Stamp Act. Previously, Parliament imposed only external taxes on imports. However, the Stamp Act provided the first internal tax on the colonists and faced vehement opposition throughout the colonies. Merchants threatened to boycott British products, and thousands of New Yorkers rioted near the location where the stamps were stored.

After 1765, the major American cities saw the formation of secret groups set up to defend their rights. Groups such as these were absorbed into the greater Sons of Liberty organization, a political group made up of American patriots formed to protect the rights of the colonists from the usurpations of the British government after 1766. Political groups such as the Sons of Liberty evolved into groups such as the Committees of Correspondence: shadow governments organized by the patriot leaders of the 13 colonies on the eve of the American Revolution. They coordinated responses to Britain and shared their plans; by 1773 they had emerged as shadow governments, superseding the colonial legislature and royal officials.

Declaration of Rights and Grievances

The Stamp Act stirred activity among colonial representatives to denounce what they saw as the disregard of colonial rights by the Crown. To protect the rights of colonists, delegates of the Stamp Act Congress drafted the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, declaring that taxes imposed on British colonists without their formal consent were unconstitutional. This was especially directed at the Stamp Act, which required that documents, newspapers, and playing cards to be printed on special stamped and taxed paper. The Declaration of Rights raised 14 points of colonial protest. In addition to the specific protests of the Stamp Act taxes, it asserted that:

- only the colonial assemblies had a right to tax the colonies (leading to the common phrase, "no taxation without representation");

- trial by jury was a right;

- the use of Admiralty Courts was abusive;

- colonists possessed all the rights of Englishmen; and

- without voting rights, Parliament could not represent the colonists.

Rise of the Sons of Liberty

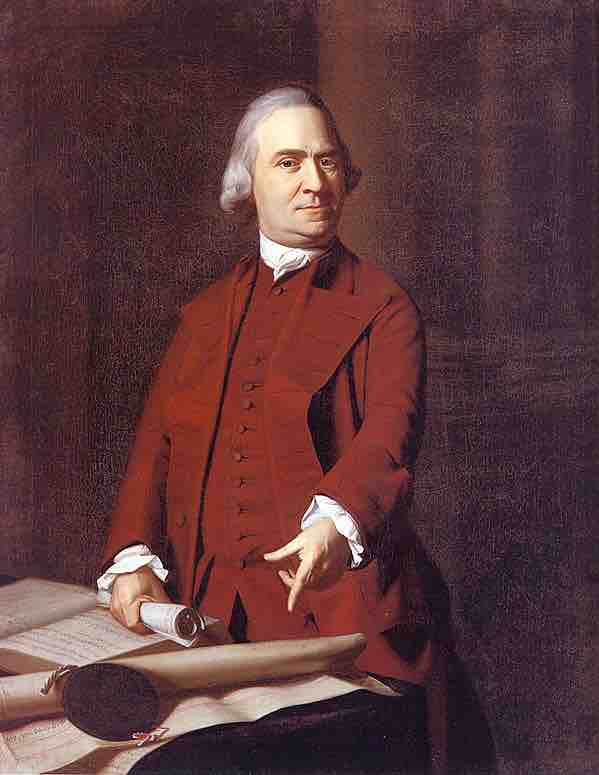

Public outrage over the Stamp Act was demonstrated most notably in Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island. It was during this time of street demonstrations that locally organized groups started to merge into an inter-colonial organization of a type not previously seen in the colonies. In Boston, the street demonstrations originated from the leadership of respectable public leaders such as James Otis, who commanded the Boston Gazette, and Samuel Adams of the "Loyal Nine" of the Boston Caucus, an organization of Boston merchants. Otis and Adams made efforts to control the people below them on the economic and social scale, but they were often unsuccessful in maintaining a delicate balance between mass demonstrations and riots. These men needed the support of the working class, but they also had to establish the legitimacy of their actions to have their protests of England taken seriously.

At the time of these protests, the Loyal Nine was more of a social club with political interests, but by December of 1765, it began issuing statements as the Sons of Liberty. Although the term "sons of liberty" had been used in a generic fashion well before 1765, it was only around February 1766, that its influence as an organized group using the formal name "Sons of Liberty," extended throughout the colonies. Its emergence led to the development of a pattern for future resistance to the British that would carry the colonies toward revolution in 1776.

Flag of the Songs of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty flag had five vertical red stripes interspersed by four white stripes.

Portrait of Samuel Adams

Samuel Adams was a leader in the colonial opposition of Stamp Act.

The organization spread month by month after independent starts in several different colonies. By November of 1765, a committee was set up in New York to correspond with other colonies, and in December, an alliance was formed between groups in New York and Connecticut. In January, a correspondence link was established between Boston and Manhattan, and by March, Providence had initiated connections with New York, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. Sons of Liberty organizations had also been established in New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia, and a local group established in North Carolina was attracting interest in South Carolina and Georgia.

Politics of Resistance

The officers and leaders of the Sons of Liberty largely consisted of middle and upper-class white men—artisans, traders, lawyers, and local politicians. Samuel Adams and his cousin, John, did not become members of the Sons of Liberty so as not to be directly connected with any violence that the organization may have been involved in. However, Samuel Adams most likely participated in the organization through writing, shared opinion, and association with prominent members that had influential power with the people.

Though they were speaking out against the actions of the British government, they still claimed to be loyal to the Crown. Their initial goal was to ensure their rights as Englishmen. Throughout the Stamp Act crisis, the Sons of Liberty professed continued loyalty to the King because they maintained a "fundamental confidence" in the expectation that Parliament would do the right thing and repeal the tax.

The Sons of Liberty knew they also needed to appeal to the masses that made up the lower classes. To do this, they relied on large public demonstrations to expand their base. While the organization professed its loyalty to both local and British established government, possible military action as a defensive measure was always part of their considerations. Several Sons of Liberty members were printers and publishers who distributed articles about the meetings and demonstrations the Sons of Liberty held, as well as its fundamental political beliefs and what it wanted to accomplish. In print, they related the major events of the struggle against the new acts to promote their cause and vilify the local officers of the British government. Office holders identified by the Sons of Liberty as being part of the Stamp Act injustice quickly fell out of favor and lost their positions once local elections were held again.

The Sons of Liberty would hold meetings to decide which candidates to support—those that would bring about the desired political change. In return, the British authorities attempted to denigrate the Sons of Liberty by referring to them as the "Sons of Violence" or the "Sons of Iniquity." The inter-communication afforded the colonies by the widespread nature of the Sons of Liberty allowed for decisive action against the later Townshend Act in 1768. One by one, the groups penned agreements limiting trade with Britain and imposing a highly effective boycott against the import and sale of British goods.

Effects of Protest

The overall effect of these protests was to both anger and unite the American people like never before. Opposition to the Stamp Act inspired both political and constitutional forms of literature throughout the colonies, strengthened the colonial political perception and involvement, and created new forms of organized resistance. These organized groups quickly learned that they could force royal officials to resign by employing violent measures and threats.