The Western Theater

The western theater of the U.S. Civil War involved military operations in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, and areas of Louisiana east of the Mississippi River. The areas west of the Mississippi, excluding states and territories bordered by the Pacific Ocean, were known as the "Trans-Mississippi Theater" of the war. The Pacific states were known as the "Pacific Coast Theater." The western theater witnessed several important campaigns.

The Union engaged in a number of offensive military operations in the western theater, forcing the Confederates to defend their positions with limited resources. The Union began campaigns in the western theater by securing Kentucky in June 1861. During this time, and in subsequent clashes over the Tennessee-Kentucky region, Ulysses S. Grant won recognition from President Lincoln for his willingness to fight and was given approval from Major General Henry W. Halleck to attack Fort Henry on the Tennessee River, which had been claimed by Confederates. Before Grant’s forces could attack, Admiral Andrew H. Foote’s naval flotilla, which consisted of both ironclads and wooden ships, bombarded the fort into surrender. The fall of Fort Henry opened the Union campaign in Tennessee and Alabama and provided the opportunity for Grant’s forces to move 12 miles east to capture Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River.

Fort Donelson did not fall as easily to Union forces. On February 14, Foote’s naval flotilla arrived along the Cumberland River, but was repulsed by Donelson’s water batteries. The next day, Confederate General Gideon J. Pillow attacked Union forces in an attempt to open up an escape route from Donelson to Nashville. Though at first the attack caused Union forces to retreat, the Confederate push forward was stalled for long enough to allow Grant’s forces to rally and prevent the southerners from escaping. Fort Donelson surrendered to the Union the next day, February 16, in what was considered a tremendous victory for the Union in terms of rebels captured and arms seized. The surrender was particularly significant for Grant’s demand that the Confederates agree to, “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender.” From then on, he was colloquially referred to as “Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

The Battle of Shiloh, or the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was another major battle in the western theater of the U.S. Civil War. It was fought April 6–7, 1862, in southwestern Tennessee and was the bloodiest battle in American history up to that point. Grant’s forces moved to an encampment at Pittsburg Landing near a small log church named "Shiloh" following the successful campaign at Fort Donelson. Their camp was set up in bivouac style without entrenchments or any planned defensive measures. The Confederates became aware of their encampment and launched a surprise attack, being fairly successful in their first day of fighting. Ultimately the Confederates lost to the Union forces on the second day when General Don Carlos Buell’s forces reached Grant’s and they launched a successful counterattack. As a result, the Confederates retreated, unable to stop the Union advance into northern Mississippi.

The Confederacy's Southwestern Campaigns

The Confederacy launched initially successful campaigns in the territory of present-day Arizona and New Mexico. The campaigns were instigated by the secessionist desires of the citizens of Texas and southern Arizona. In Texas, local troops took over the federal arsenal in San Antonio with the intention of taking the territories of northern New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, and California. Residents in southern Arizona adopted a secession ordinance and requested aid from Confederate forces in Texas, both to oust the Union Army forces in Arizona and to resist raids by Apaches after U.S. Army units were moved out.

In 1861, the Confederate States Army launched a successful campaign into Arizona and New Mexico. After Confederate victories, Colonel John Baylor proclaimed the creation of the Confederate territory of Arizona. Confederate soldiers and militia continued to fight against Apaches with battles peaking in 1861.

Confederate troops were unsuccessful in attempts to press northward from their acquisitions in Arizona. In 1862, Union reinforcements arrived from California. Union forces won an important victory at the Battle of Glorieta Pass (March 26–28, 1862). The battle was small in terms of troops engaged and casualties inflicted, but important in that it effectively stopped the Confederacy’s northward advance. A Confederate victory would have eased the advance to Fort Union in New Mexico and to Denver.

In April, the California Column of the Union Army drove the Confederates from Tucson after the Battle of Picacho Pass. After a small skirmish, Confederate forces withdrew due to a lack of supplies. The conflict ended the Confederate campaign in the Southwest, leaving the area west of Texas in Union hands for the remainder of the war. The Battle of Pichaco Pass was also the westernmost engagement of the War.

Conflict over Missouri

Missouri was a border state whose loyalties were courted by both Union and Confederate leaders. Slavery was legal in the state, and Missouri had a well-organized and militant secessionist movement. Nevertheless, the Missouri legislature voted by a ratio of more than two-to-one to remain in the Union.

Missouri became a site of conflict when governor Claiborne F. Jackson, a staunch supporter of the Confederacy, led his small state guard to the federal arsenal at St. Louis. Jackson's force soon joined with Confederate armies and waged a campaign to secure control of Missouri. The Confederates won initial victories at the Battle of Wilson's Creek and Lexington. However, Confederate forces were driven back by the arrival of a large Union force in February 1862. Union control of Missouri was ensured by a victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, on March 7–8.

Thereafter, a guerrilla conflict developed in Missouri. Gangs of Confederate insurgents, commonly known as “bushwhackers,” ambushed and battled Union troops and Unionist state militia forces. Fighting also occurred between pro- and anti-Union Missourians. Both sides carried out large-scale atrocities against civilians, ranging from forced resettlement to murder.

The Union's Campaigns in Texas and Western Louisiana

Starting in 1862 and continuing through the end of the war, the Union mounted several attempts to capture the trans-Mississippi regions of Texas and Louisiana. With Atlantic ports blockaded, ports in Texas and Louisiana became havens for blockade running. Referred to as the "back door" of the Confederacy, ports in Texas and western Louisiana continued to ship cotton crops that could be transferred overland to Mexican border towns and then shipped to Europe in exchange for badly needed supplies. Determined to close this trade, the Union mounted several invasion attempts of Texas, each of them unsuccessful. The Union's disastrous Red River Campaign in western Louisiana effectively ended the Union's attempts to invade the region.

Isolated from events in the East, the Civil War continued at a low level in the Trans-Mississippi theater for several months after Lee's surrender in April 1865. The last battle of the war occurred at Palmito Ranch in southern Texas—a Confederate victory.

Campaigns in Indian Territory

The land formally designated as "Indian Territory" covered most of present-day Oklahoma. This territory was an unorganized region, reserved for Native American tribes of the southeastern United States. Indian Territory hosted numerous skirmishes and seven officially recognized battles in which different Native American groups allied with the Union or Confederacy. Significant campaigns include the Sioux Wars in Minnesota (1862) and campaigns against the Navajo in Arizona (1864).

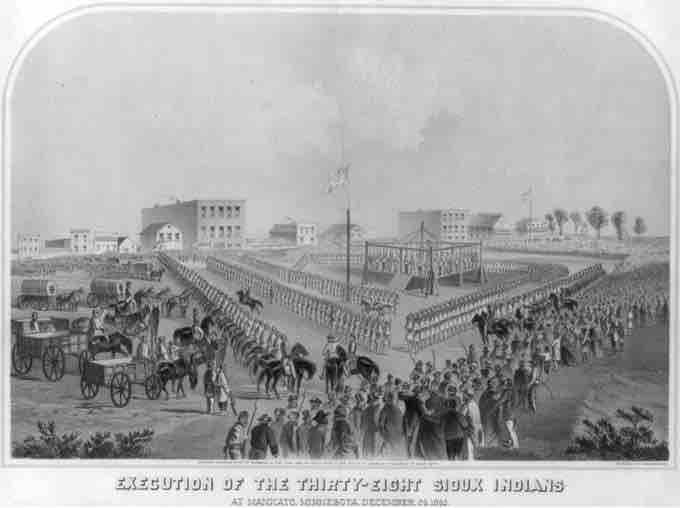

"Execution of the Thirty-Eight Sioux Indians"

The last act associated with the Sioux Wars in 1862: after the Union Army defeated the attacking Dakota tribes, the tribes' leaders were tried and executed.