Recruitment and Training

In April 1861, at the beginning of the American Civil War, there were only 16,000 men in the U.S. Army. Of these, many Southern officers resigned and joined the Confederate States Army. The U.S. Army consisted of ten regiments of infantry, four of artillery, two of cavalry, two of dragoons, and one of mounted infantry. The regiments were scattered widely. Of the 197 companies in the army, 179 occupied 79 isolated posts in the West, and the remaining 18 manned garrisons east of the Mississippi River, mostly along the Canadian border and on the Atlantic coast.

Union Recruitment and Conscription

With the secession of the Southern states, and with this drastic shortage of men in the army, President Abraham Lincoln called on the states to raise a force of 75,000 men for three months to put down the “insurrection.” Lincoln's call forced the border states to choose sides. Four seceded, making the Confederacy 11 states strong.

The war proved to be longer and more extensive than anyone, North or South, had expected. On July 22, 1861, Congress authorized a volunteer army of 500,000 men. Initially, the call for volunteers was easily met by patriotic Northerners, abolitionists, and even immigrants who enlisted for a steady income and meals. More than 10,000 Germans from New York and Pennsylvania immediately responded to Lincoln's call, and the French also were quick to volunteer. As more men were needed, however, the number of volunteers fell, and both money bounties and forced conscription became necessary.

On March 3, 1863, Congress enacted the Enrollment Act, also known as the "Civil War Military Draft Act," to bolster the manpower of the Union Army. The act required every male citizen and male immigrant who had filed for citizenship between the ages of 20 and 45 to enroll in the army. The act was very controversial and led to a number of riots, including the infamous New York City draft riots during what was known as Draft Week (July 13–16, 1863). The New York City draft riots were the largest civil and racial insurrection in American history aside from the Civil War. The unrest was primarily driven by the working-class population and particularly Irish immigrants. A provision in the act allowed those who paid a $300 substitution fee to be exempt from service.

While the New York City draft riots began an an expression of discontent over the draft, the violence was also directed toward African Americans with death tolls reaching 119. Conditions were such within the city that President Lincoln was forced to redirect militia and volunteer troops from the recent Battle of Gettysburg up to New York in order to contain the situation. The forces arrived after the first day of rioting, at which point significant damage had already been done to several buildings, churches, African-American homes, and other institutions such as the Colored Orphan Asylum, which was completely burned to the ground. As a result of the racially driven violence, many African Americans left Manhattan permanently. Yet despite the controversial Enrollment Act and the outcry that followed, at least 2.5 million men—the majority of whom were volunteers—served in the Union Army between April 1861 and April 1865.

The Confederates also conscripted soldiers for their army. The Conscription Act, passed in April 1862, was the first of its kind in U.S. history. It called for all able-bodied white men between the ages of 18 and 35 to enroll in the army for a three-year term. It also extended the term of service for those who had previously enrolled from one year to three. Men who worked in industries considered critical to the Confederate cause, such as railroad and river workers, miners, and teachers, were exempt from the draft. The act was amended twice within the year. On September 27, the maximum age of conscription was extended to 45. On October 11, the “Twenty Nigger Law” provided an exemption from service for men who owned 20 or more slaves. As the Confederates suffered losses in battle and struggled in the face of a much larger Union force, the act was amended further, disallowing wealthy men to pay a substitution fee in order to avoid service and extending the lower and upper age limits to 17 and 50 respectively.

Proportions of Professionals on Both Sides

It is a misconception that the South held an advantage because of the large percentage of professional officers who resigned to join the Confederate States Army. At the start of the war, there were 824 graduates of the U.S. Military Academy on the active list; of these, 296 resigned or were dismissed, and 184 of those became Confederate officers. Of the approximately 900 West Point graduates who were then civilians, 400 returned to the Union Army and 99 to the Confederate. Therefore, the ratio of Union to Confederate professional officers was 642 to 283.

One of the resigning officers was Robert E. Lee, who had initially been offered the assignment as commander of a field army to suppress the rebellion. Lee disapproved of secession, but refused to bear arms against his native state, Virginia, and resigned to accept the position as commander of Virginia forces. He eventually became the commander of the Confederate States Army. The South did have the advantage of being home to other military colleges, such as The Citadel and Virginia Military Institute, but these institutions produced fewer officers. Only 26 enlisted men and noncommissioned officers are known to have left the regular U.S. Army to join the Confederate Army, all by desertion.

Participation of African-American Soldiers

The inclusion of African Americans as combat soldiers became a major issue. Eventually, it was realized, especially given the valiant efforts of the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, that African Americans were fully able to serve as competent and reliable soldiers. The 54th Regiment was an infantry regiment that saw extensive service with the Union Army throughout the Civil War and was one of the first official African-American units in the United States. The assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863, helped raise their regiment to prominence. Of the 600 men who charged on the fort, 272 were either killed, wounded, or captured: the highest casualty count for the 54th in a single engagement during the war. Though the Union did not prevail in taking and holding the fort, word of the 54th Regiment’s valor spread quickly and received great praise.

Another notable story of African-American service to the Union involved Robert Smalls, who, while still a slave, won fame by defecting from the Confederacy and commandeering a Confederate transport ship he was piloting to Union hands. He later met with Edwin Stanton, secretary of war, to argue for including African Americans in combat units. This led to the formation of the first combat unit for black soldiers, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers.

Regiments for black soldiers were eventually referred to as "United States Colored Troops." African Americans were paid less than white soldiers until late in the war and were, in general, treated harshly. Even after the end of the war, they were not permitted (by Sherman's order) to march in the great victory parade through Washington, D.C. In general, the Union Army was composed of many different ethnic groups, including large numbers of immigrants. About 25 percent of the white people who served in the Union Army were foreign-born.

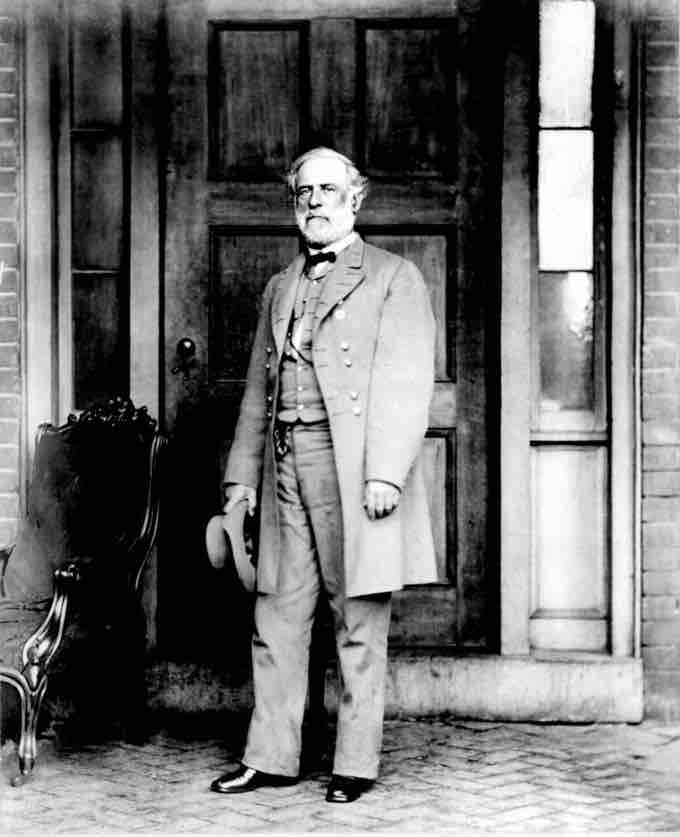

General Robert E. Lee

General Lee had been offered the command of Union armies but declined when his home state of Virginia seceded. His superior generalship was an important factor in Confederate victories in the eastern theater. He was lionized as the embodiment of what had been most noble in the Confederacy.