Background

The U.S. Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act in July 1862. It freed slaves of owners in rebellion against the United States, and a militia act empowered the president to use freed slaves in any capacity in the army. President Abraham Lincoln was concerned with public opinion in the four border states that remained in the Union, as they had numerous slaveholders, as well as with Northern Democrats who supported the war but were less supportive of abolition than many Northern Republicans.

Lincoln opposed early efforts to recruit black soldiers, although he accepted the army's using them as paid workers. Union Army setbacks in battles over the summer of 1862 led Lincoln to emancipate all slaves in states at war with the Union. In September 1862, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, announcing that all slaves in rebellious states would be free as of January 1, 1863. Recruitment of "colored" regiments began in full force following the Proclamation.

Establishment of the USCT

The United States Colored Troops (USCT) were regiments of the U.S. Army during the American Civil War that were composed of African-American ("colored") soldiers. The U.S. War Department issued General Order Number 143 on May 22, 1863, establishing a "Bureau of Colored Troops" to facilitate the recruitment of African-American soldiers to fight for the Union Army. By the end of the Civil War, 175 USCT regiments composed of more than 178,000 free blacks and freedmen constituted approximately one-tenth of the Union Army. Regiments—including infantry, cavalry, engineers, light artillery, and heavy artillery units—were recruited from all states of the Union. Their service bolstered the Union war effort at a critical time.

African-American Service

In actual numbers, African-American soldiers comprised 10 percent of the entire Union Army. Losses among African Americans were high, and from all reported casualties, approximately 20 percent of all African Americans enrolled in the military lost their lives during the Civil War. The USCT suffered 2,751 combat casualties during the war, and 68,178 losses from all causes. Disease caused the most fatalities for all troops. Notably, the mortality rate of African-American soldiers was significantly higher than that of white soldiers.

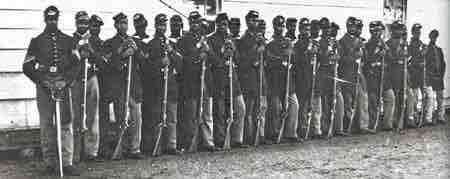

Picture of African-American infantry

The 4th U.S. Colored Infantry.

Both enslaved and free African Americans assisted the Union in matters of intelligence, their concerted efforts known as "Black Dispatches." Notable spies for the Black Dispatches included Mary Bowser and Harriet Tubman. Although Tubman is primarily remembered for her contributions to freeing slaves via the Underground Railroad, she also used her extensive knowledge of the terrain in the South to help the Union Army. She was the first woman to lead U.S. soldiers into combat when she took a contingent of soldiers under the command of Colonel James Montgomery behind enemy lines in South Carolina where troops destroyed plantations and freed 750 slaves.

Despite these numerous contributions, discrimination persisted against African Americans in the armed forces. Although white privates received payment of $16 per month plus an optional clothing allowance of $3.50, soldiers of African descent only received $10 a month plus an optional deduction of $3 for clothing. There was no official attempt to make payment more equitable until June 15, 1864, when Congress granted equal pay to African-American soldiers. Aside from discrimination in pay, African-American soldiers also were disproportionately assigned hard-labor duties as opposed to combat assignments.

Confederate Treatment of African-American Soldiers

On the Confederate side, both free and enslaved African Americans were used for labor, but the issue over whether to arm them, and under what terms, became a major source of debate, and no significant numbers were ever raised or recruited. The attitude within the Confederacy toward Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was very negative, with many calling for the trial of any Union soldiers captured as slave insurrectionists, an offense punishable by death.

On March 16, 1864, Confederate forces began a month-long cavalry raid in Tennessee and Kentucky to capture Union prisoners and supplies, as well as demolish forts and other Union posts, on the path to Memphis. By April 12, Brigadier General James Chalmers’s division surround Fort Pillow, an outpost most recently taken up by approximately 600 Union soldiers, almost evenly split among African-American and white soldiers. After five and a half hours of bombardment, the Confederate forces demanded surrender from the Union forces, promising that any soldiers who surrendered would be treated as prisoners of war. The Confederates had just received a fresh supply of ammunition and communicated to the Union forces that they could easily capture the fort. The Union forces requested an hour to consider the offer, but Confederate Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest rebutted that they would only allow the Union forces 20 minutes to consider their offer. In reply, Union Major William Bradford refused surrender, and Confederate forces began their assault.