On June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress established the Continental Army, raising 22,000 troops from the Boston area and 5,000 from New York. Many of these troops had little training or military experience; the minimum enlistment age was 16. On June 15, 1775, George Washington was elected as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army.

Continental Army, 1779-1783 by Henry Ogden, ca. 1897

This painting depicts the Infantry of the Continental Army.

As the Continental Congress increasingly adopted the responsibilities and posture of a legislature for a sovereign state, the role of the Continental Army was the subject of considerable debate. Though the war against the British required the discipline and organization of a modern military, many Patriots objected to maintaining a standing army. Washington was never financially compensated for his service as Army Commander. The financial responsibility for providing pay, food, shelter, clothing, arms, and other equipment to army units was given to the 13 states by Congress. Unfortunately, the states frequently failed to fulfill these obligations. In 1776, Congress passed the "Eighty-eight Battalion Resolve", ordering each state to contribute regiments in proportion to their population.

Lack of funds for the war effort was a major concern for Congress and resulted in poor conditions for soldiers. Standard conditions for the Continental Army included low pay, hard work, freezing winters, hot summers, poor clothing and shelter, little food, harsh discipline, and a strong likelihood of becoming a casualty. Recruitment depended on the voluntary enlistment of Patriots from each of the 13 states. Early in the war, rising patriotism contributed to high rates of enlistment. However, as the war dragged on, bounties and other incentives became increasingly commonplace. Two major mutinies late in the war drastically diminished the reliability of two of the main units, and officers were faced with constant discipline problems. High turnover was a consistent issue, particularly in the winter of 1776-77.

American soldiers at the siege of Yorktown, by Jean-Baptiste-Antoine DeVerger

This watercolor features several Continental foot soldiers, including an African American soldier from the first Rhode Island Regiment.

Congress’ hesitance to establish a standing army resulted in short, one-year enlistment periods in the beginning of the war. In 1777, enlistment terms were extended to three years or "the length of the war". In the later years of the war (1781-1782), Congress was bankrupt and it was difficult to replace the soldiers whose three-year terms had expired. Popular support for the war was at an all-time low, and Washington had to put down mutinies both in the Pennsylvania and New Jersey Lines.

Congress also created a Continental Navy in 1775. The main goal of naval operations was to intercept shipments of British supplies and disrupt British maritime commerce. The initial fleet consisted of converted merchantmen; later in the war Congress commissioned several warships. Ultimately, the naval effort contributed little to the overall outcome of the rebellion. Following the war, Congress dissolved the navy due to lack of funds.

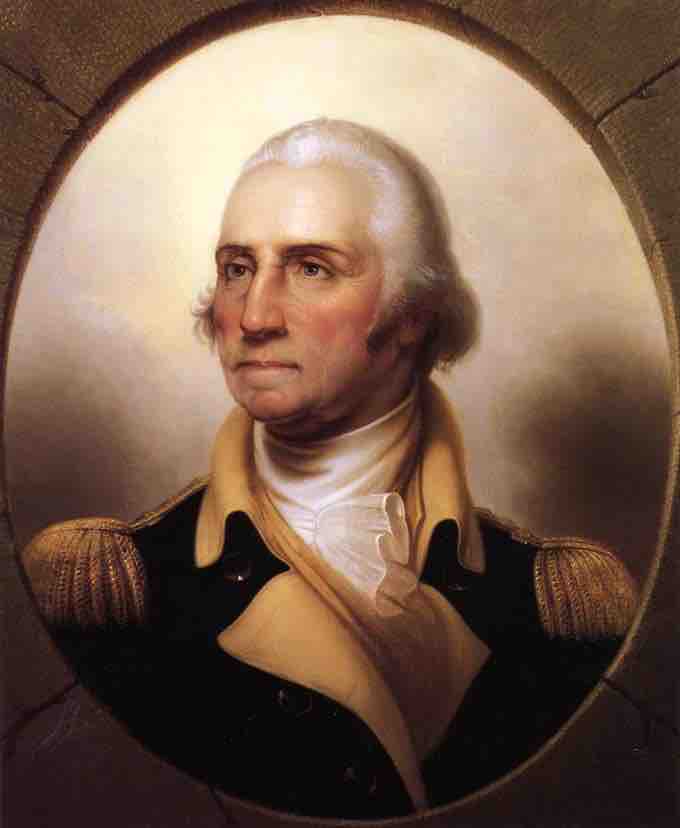

George Washington by Rembrandt Peale, ca. 1850

George Washington served as commander-in-chief for the duration of the Revolutionary War without compensation.