When the Revolutionary War began, the 13 colonies lacked a professional army or navy. Each colony sponsored a local militia. Militiamen were lightly armed, had little training, and usually did not have uniforms. Their units served for only a few weeks or months at a time, were reluctant to travel far from home, and thus were unavailable for extended operations. Furthermore, they lacked the training and discipline of soldiers with more experience.

Seeking to coordinate military efforts, the Continental Congress established a regular army on June 14, 1775, and appointed George Washington as commander-in-chief. On July 18, 1774, Congress requested that all colonies form militias of able-bodied men between the ages of 16 and 50. Due to the lack of requirements for parental consent in many colonies, it was not uncommon for men younger than 16 to enlist. Soldiers in the Continental Army were unpaid volunteers and enlistment periods varied from one to three years. Typically, enlistment periods were shorter during the beginning of the Revolutionary War due to the Continental Congress’ fear of the Continental Army evolving into a permanent standing army. Yet over time, as turnover increased, longer enlistments were approved.

The development of the Continental Army was always a work in progress, and Washington used both his regulars and state militia throughout the war. Sometimes militias operated independently of the Continental Army, but for the most part, they were used to augment and support the army regulars during campaigns. Approximately 250,000 men served as regulars or as militiamen for the revolutionary cause in the eight years of the war, but there were never more than 90,000 men under arms at one time.

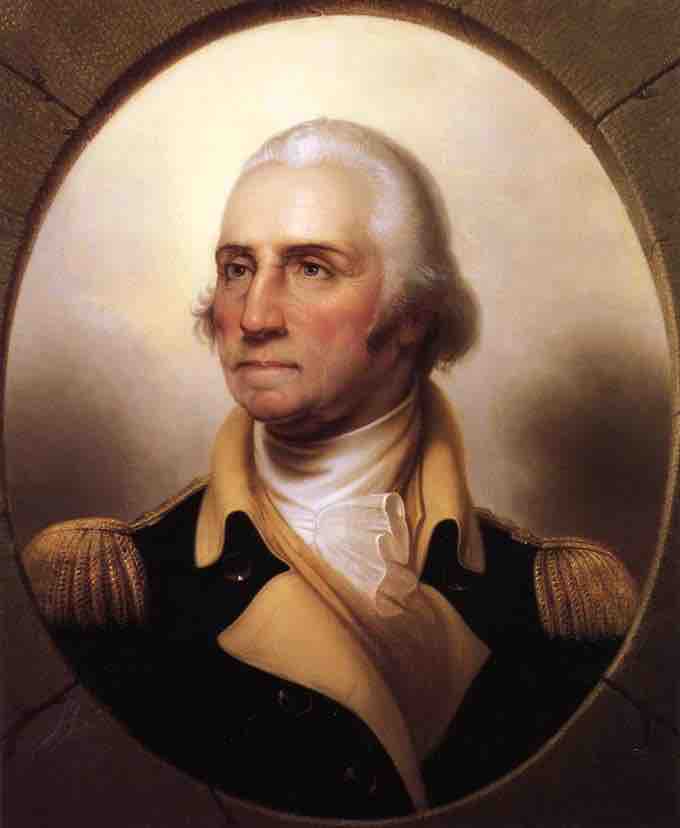

George Washington, by Rembrandt Peale, ca. 1850

Portrait of General George Washington, who was appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental Army on June 15, 1775.

Minutemen were members of teams of select men from the American colonial partisan militia during the American Revolutionary War. They provided a highly mobile, rapidly deployed force that allowed the colonies to respond immediately to war threats, hence the name. The minutemen constituted about a quarter of the entire militia.

Minutemen

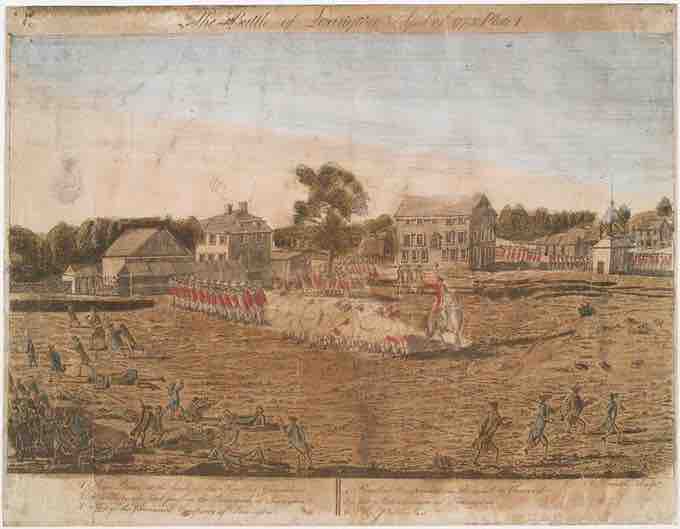

The Battle of Lexington, April 19th, 1775. Blue-coated militiamen in the foreground flee from the volley of gunshots from the red-coated British Army line in the background. These American militias were an important supplement to the Continental Army.

The success of minutemen at Lexington and Concord is offset by the long history of failures of the colonial militia. George Washington is well-known for his scathing opinion of the shortcomings of militia forces. However, the minuteman model for militia mobilization, married with a very professional, small standing army, was the primary model for the land forces of the United States up until 1916 when the National Guard was established.

Equipment, Training, and Tactics

Most colonial militia units were not provided weapons or uniforms and were required to equip themselves. Many simply wore their own farmer's or workman's clothes, and in some cases, they wore cloth hunting frocks. Most used fowling pieces, though rifles were sometimes used where available. Neither fowling pieces nor rifles had bayonets. Ammunition and supplies were scarce and were constantly being seized by British patrols. As a precaution, these items were often hidden or left behind by minutemen in fields, wooded areas, or private residences. Some colonies purchased muskets, cartridge boxes, and bayonets from England, and maintained armories within the colony.

The Continental Army was troubled by poor logistics, inadequate training, short enlistments, interstate rivalries, and Congress’s inability to compel the states to finance or equip its troops with food and supplies. Through its many trials and errors, army leadership was crucial to preserving unity and discipline throughout the war. In the winter of 1777–1778, with the addition of Prussian Baron von Steuben, army regulars began to receive European-style military training, which vastly improved training and discipline. Members of the militias, however, were not included in this new mode of training. Rather than fight formal battles in the traditional dense lines and columns, militiamen proved a better resource when used as irregulars, primarily as skirmishers and sharpshooters.

Their experience suited irregular warfare. Most were familiar with frontier hunting. The Indian Wars, and especially the recent French and Indian War, had taught both the men and officers the value of irregular warfare, while many English troops fresh from Europe were less familiar with this type of combat. The long rifle was also well suited to this role. The rifling (grooves inside the barrel) gave it a much greater range than the smooth-bore musket, although it took much longer to load. Because of the lower rate of fire, rifles were not used by regular infantry, but were preferred for hunting. When performing as skirmishers, the militia could fire and fall back behind cover or other troops before the British could get into range. The wilderness terrain that lay just beyond many colonial towns, very familiar to the local minuteman, favored this style of combat. In time, however, loyalists like John Butler and Robert Rogers mustered equally capable irregular forces. In addition, many British commanders learned from experience and effectively modified their light infantry tactics and battle dress to suit conditions in North America.

Through the remainder of the revolution, militias moved to adopt the minuteman model for rapid mobilization. With this rapid mustering of forces, the militia proved its value by augmenting the Continental Army on a temporary basis. This was seen at the Battles of Hubbardton and Bennington in the north and at Camden and Cowpens in the south.

Continental Army

This illustration depicts uniforms and weapons used during a period (1779–1783) of the American Revolution. These soldiers would have been a part of the Continental Army rather than militiamen.