Many mixed-race families dated back to colonial Virginia, when white women, generally indentured servants, produced children with men of African descent, both slave and free. Because of the mother's status, those children were born free and often married other free people of color.

The belief in racial "purity" drove Southern culture's vehement prohibition of sexual relations between white women and black men, but this same culture essentially protected sexual relations between white men and black women. The result was numerous mixed-race children. The children of white fathers and slave mothers were mixed-race slaves whose appearance was generally classified as "mulatto," a term that initially meant a person with white and black parents, but grew to encompass any apparently mixed-race person.

White and black individuals often were linked together in very intimate ways. Many mixed-race house servants were actually related to white members of the household. Often these relationships were the product of unequal power structures and sexual abuse; however, the children resulting from these relationships were sometimes offered greater opportunities for education, skilled professional development, and even freedom and acceptance within white society. In many households, for instance, the way in which slaves were treated depended on the slave's skin color. Darker-skinned slaves worked in the fields while lighter-skinned slaves worked in the house and had comparatively better clothing, food, and housing. Sometimes planters used mixed-race slaves as house servants or favored artisans because they were their own children or the children of their relatives.

Planters who had mixed-race children sometimes arranged for their children's education, even sending them to schools in the North, or securing their employment as apprentices in crafts. In its early years, Wilberforce University, which was founded in Ohio in 1856 for the education of African-American youth, was largely financed by wealthy Southern planters who wanted to provide for the education of their mixed race children. Some planters freed both the children and the mothers of their children.

Though fewer in number than in the Upper South, free blacks in the Deep South (especially in Louisiana and Charleston, South Carolina) were often mixed-race children of wealthy planters and received transfers of property and social capital. Despite their familial connections and freedom, many mixed-race individuals still faced discrimination and prejudice due to the color of their skin.

Slave patrol

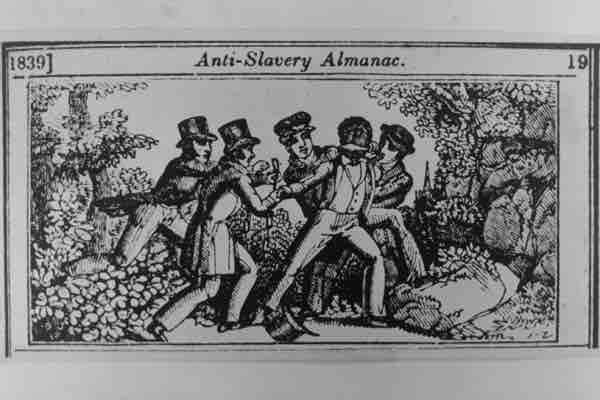

A woodcut from the abolitionist Anti-Slavery Almanac (1839) depicts a slave patrol capturing a fugitive slave.