The Underground Railroad was a network of secret routes and safe houses used by nineteenth-century black slaves in the United States to escape to free states and Canada with the aid of abolitionists and those sympathetic to their cause. The term is also applied to the abolitionists—black and white, free and enslaved—who aided the fugitives. Some routes led to Mexico or overseas. The network was formed in the early nineteenth century and reached its height between 1850 and 1860. One estimate suggests that by 1850, 100,000 slaves had escaped via the "Railroad."

Political Background

With heavy political lobbying, the Compromise of 1850, passed by Congress after the Mexican-American War, stipulated a more stringent Fugitive Slave Law. Ostensibly the compromise redressed all regional problems; however, it coerced officials of free states to assist slave catchers if there were runaway slaves in the area and granted slave catchers national immunity when in free states to do their job. Additionally, it made it possible that free blacks of the North could be forced into slavery even if they had been freed earlier or never been slaves at all because suspected slaves were unable to defend themselves in court and it was difficult to prove a free status. As a de facto bribe, judges were paid more ($10) for a decision that forced a suspected slave back into slavery than for a decision finding the slave to be free ($5). Thus, many Northerners who would have otherwise been able and content to ignore the persistence of slavery in the South chafed under what they saw as a national sanction on slavery, comprising one of the primary grievances of the Union cause during the Civil War.

Structure

The escape network of the Underground Railroad was not literally underground or a railroad. It was figuratively "underground" in the sense of being a covert form of resistance. It came to be referred to as a "railroad" due to the use of rail terminology in the code used by its participants. The Underground Railroad consisted of meeting points, secret routes, transportation, safe houses, and assistance provided by abolitionists and sympathizers. Individuals were often organized in small, independent groups. These small groups helped to maintain secrecy because individuals knew some connecting "stations" along the route but few details of their immediate area. Escaped slaves would move north along the route from one way station to the next. "Conductors" on the railroad came from various backgrounds and included free-born blacks, white abolitionists, former slaves (either escaped or manumitted), and Native Americans. Churches often played a role, especially the Society of Friends (Quakers), Congregationalists, Wesleyans, and Reformed Presbyterians, as well as certain sects of mainstream denominations such as the Methodist church and American Baptists.

Route

To reduce the risk of infiltration, many people associated with the Underground Railroad knew only their part of the operation and little to nothing of the whole scheme. Written directions were discouraged for the same reason. Additionally, because many freedom seekers could not read, visual and audible clues such as patterns in quilts, song lyrics, and star positions provided directional cues along the way. Conductors moved the runaways from station to station. Often the conductor would pretend to be a slave to enter a plantation. Once a part of a plantation, the conductor would direct the runaways to the North. Slaves would travel at night around 10 to 20 miles to each station or “depot,” resting spots where the runaways could sleep and eat. The stations were out of the way places such as barns and were held by “station masters” who would provide assistance such as sending messages to other stations and directing fugitives on the path to take to their next stop. There were also those known as "stockholders" who gave money or supplies for assistance.

Traveling Conditions

The journey was often considered particularly difficult and dangerous for women or children, yet many still participated. In fact, one of the most famous and successful abductors, or people who secretly traveled into slave states to rescue those seeking freedom, was Harriet Tubman.

Harriet Tubman (photo by H.B. Lindsley), ca. 1870.

A worker on the Underground Railroad, Tubman made 13 trips to the South, helping to free more than 70 people.

Due to the risk of discovery, information about routes and safe havens was passed along by word of mouth. Southern newspapers of the day were often filled with pages of notices soliciting information about escaped slaves and offering sizable rewards for their capture and return. Federal marshals and professional bounty hunters known as "slave catchers" pursued fugitives as far as the Canadian border.

The risk was not limited solely to actual fugitives. Because strong, healthy black people in their prime working and reproductive years were treated as highly valuable commodities, it was not unusual for free blacks—both freedmen and those who had never been slaves—to be kidnapped and sold into slavery. "Certificates of freedom"—signed, notarized statements attesting to the free status of individuals—easily could be destroyed and thus afforded their holders little protection. Under the terms of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, when suspected fugitives were seized and brought to a special magistrate known as a "commissioner," they had no right to a jury trial and could not testify on their own behalf. The marshal or private slave catcher needed only to swear an oath to acquire a writ of replevin for the return of property.

Arrival in Canada

Estimates vary widely, but at least 30,000 slaves, and potentially more than 100,000, escaped to Canada via the Underground Railroad. The largest group settled in Upper Canada, called Canada West from 1841 and known today as Southern Ontario, where numerous black Canadian communities developed. Upon arriving at their destinations, many fugitives were disappointed. Despite the British colonies’ abolition of slavery in 1834, discrimination was still common.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in the United States, many black refugees enlisted in the Union Army, and while some later returned to Canada, many remained in the United States. Thousands of others returned to the American South after the war ended. The desire to reconnect with friends and family was strong and most were hopeful about the changes emancipation and Reconstruction would bring.

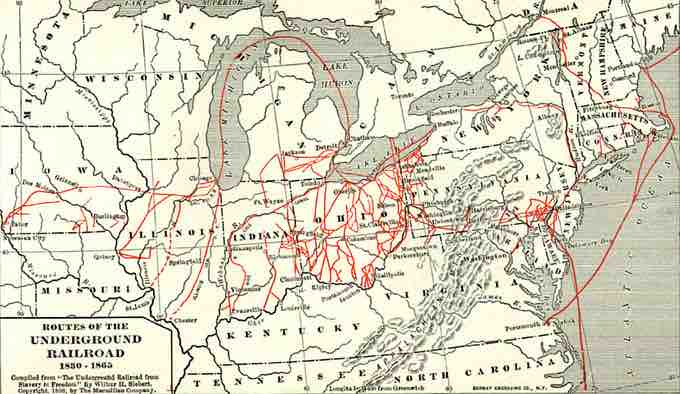

Underground Railroad routes

This map shows a complex web of Underground Railroad routes.