The Chesapeake Bay

The strategic location of the Chesapeake Bay near America's capital made it a prime target for the British during the War of 1812. Starting in March of 1813, a squadron under British Rear Admiral George Cockburn started a blockade and raided towns along the bay from Norfolk to Havre de Grace.

On July 4, 1813, Joshua Barney, a Revolutionary War naval hero, convinced the Navy Department to build the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla, a squadron of twenty barges to defend the Chesapeake Bay. Launched in April of 1814, the squadron was quickly cornered in the Patuxent River; while successful in harassing the Royal Navy, the squadron was powerless to stop the British campaign that ultimately led to the burning of Washington.

The Burning of Washington, D.C.

The expedition against Washington, led by Cockburn and General Robert Ross, was carried out between August 19 and 29, 1814, as the result of the hardened British policy of 1814. British and American commissioners had convened for peace negotiations at Ghent in June of that year; however, Admiral Warren had been replaced as commander in chief by Admiral Alexander Cochrane, with reinforcements and orders to coerce the Americans into a favorable peace.

Governor-in-Chief of British North America Sir George Prevost had written to the admirals in Bermuda, calling for retaliation for destructive American raids into Canada, most notably the Americans' burning of York in 1813. A force of 2,500 soldiers under General Ross had recently arrived in Bermuda aboard the HMS Royal Oak, three frigates, three sloops, and ten other vessels. Released from the Peninsular War in Europe by British victory, the British intended to use these ships for diversionary raids along the coasts of Maryland and Virginia. In response to Prevost's request, the British decided to employ this force, together with the naval and military units already on the station, to strike at Washington, D.C.

Burning of Washington D.C.

This drawing shows the capture and burning of Washington, D.C. by the British in 1814. 1876 publication.

On August 24, U.S. Secretary of War John Armstrong insisted that the British would attack Baltimore rather than Washington, even when the British Army was obviously on its way to the capital. The inexperienced U.S. militia, which had congregated in Maryland to protect the capital, was routed in the Battle of Bladensburg, opening the route to Washington. After the U.S. government officials fled from Washington, First Lady Dolley Madison remained behind to organize the slaves and staff to save valuables from the British. Although she was able to save valuables from the presidential mansion, both she and President James Madison were forced to flee to Virginia.

Upon arriving, the British commanders ate the supper that had been prepared for the president before they burned the presidential mansion. A furious storm swept into Washington, D.C. later that same evening, sending tornadoes into the city that caused even more damage but finally extinguished the fires with torrential rains. The naval yards were set afire at the direction of U.S. officials to prevent the capture of naval ships and supplies. The British left Washington, D.C. as soon as the storm subsided. The successful British raid on Washington, D.C., dented American morale and prestige.

The Battle of Baltimore

Having destroyed Washington's public buildings, including the president's mansion and the Treasury, the British Army next moved to capture Baltimore, a busy port and a key base for American privateers. The subsequent Battle of Baltimore began with the British landing at North Point, where they were met by American militia. An exchange of fire began, with casualties on both sides. General Ross was killed by an American sniper as he attempted to rally his troops. The sniper himself was killed moments later, and the British withdrew. The British also attempted to attack Baltimore by sea on September 13 but were unable to reduce Fort McHenry at the entrance to Baltimore Harbor, due to recent fortifications.

The Battle of Fort McHenry

The Battle of Fort McHenry was no battle at all. British guns and rockets bombarded the fort and then moved out of range of the American cannons, which returned no fire. Admiral Cochrane's plan was to coordinate with a land force, but from that distance, coordination proved impossible. The British called off the attack and left.

All the lights were extinguished in Baltimore the night of the attack, and the fort was bombarded for 25 hours. The only light was given off by the exploding shells over Fort McHenry, illuminating the flag that was still flying over the fort. The defense of the fort inspired the American lawyer Francis Scott Key to write a poem that would eventually provide the lyrics to "The Star-Spangled Banner."

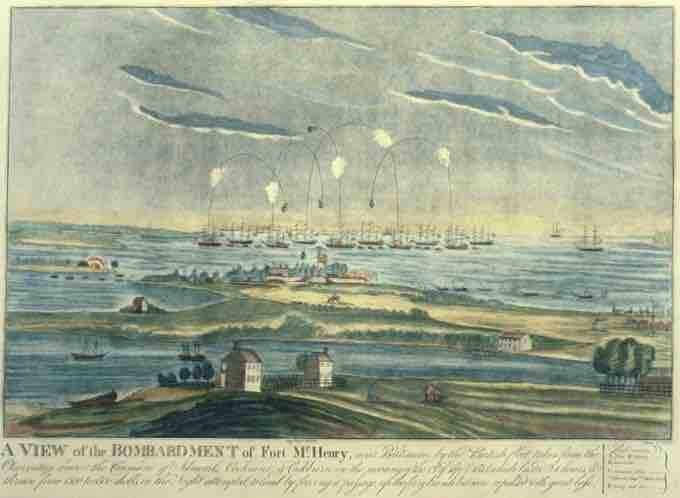

The bombardment of Fort McHenry

A contemporary rendering of the engagement that provided the inspiration for "The Star-Spangled Banner."