Introduction

The War of 1812 (1812–1815) was fought between the United States and the British Empire as well as Britain's American Indian allies. It was chiefly fought on the Atlantic Ocean and on the land, coasts, and waterways of North America. The conflict stemmed from the unfinished business of the American Revolution and the pressures resulting from Great Britain's struggle with France.

Origins of the War

British Impressment and the Embargo Act of 1807

The origins of the War of 1812, often called the "Second War of American Independence," are found in the unresolved issues between the United States and Great Britain. One major cause was the British practice of impressment, whereby American sailors were taken at sea and forced to fight on British warships; this issue was left unresolved by Jay’s Treaty in 1794. France and England, engaged in the Napoleonic Wars (which raged between 1803 and 1815), both openly seized American ships at sea. England was the major offender: The Royal Navy, following a time-honored practice, “impressed” American sailors by forcing them into British service.

The issue came to a head in 1807 when the HMS Leopard, a British warship, fired on a U.S. naval ship, the Chesapeake, off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia. The British then boarded the ship and took four sailors. After the Leopard-Chesapeake affair, Jefferson chose what he thought was the best of his limited options and responded to the crisis through economic means. He initiated a sweeping ban on trade, known as the Embargo Act of 1807. This law prohibited American ships from leaving their ports until Britain and France agreed to stop seizing them at sea. The embargo, however, caused far more damage to America's economy than to Britain's. The embargo was difficult to enforce and smuggling became common. Jefferson's embargo was particularly unpopular in New England, where merchants preferred the indignities of impressment to the halting of overseas commerce, and tension among American citizens grew.

At the very end of his second term, Jefferson signed the Non-Intercourse Act of 1808, which lifted all embargoes on American shipping except for those vessels bound for British or French ports. As this proved to be unenforceable, Macon's Bill Number 2 replaced the Non-Intercourse Act in 1810. This lifted all embargoes but stated that if either France or Great Britain were to cease their interference with American shipping, the United States would reinstate an embargo on the other nation. Napoleon, seeing an opportunity to make trouble for Great Britain, promised to leave American ships alone, and the United States reinstated the embargo with Great Britain, moving closer to a declaration of war.

The USS Chesapeake painted by F. Muller

The Leopard-Chesapeake Affair of 1807 heightened British-American tensions when the HMS Leopard fired on and boarded the American warship, USS Chesapeake.

American Expansionism

Another underlying cause of the War of 1812 was British support for American Indian resistance to U.S. western expansion. For many years, European-American settlers in the western territories had besieged the American Indians living there. Under President Jefferson, two American Indian policies existed: one that forced American Indians to adopt American ways of agricultural life, and another that sought to aggressively drive them into debt in order to force them to sell their lands.

The Algonquian and Iroquoian nations of the Great Lakes and the Ohio Country organized in opposition to U.S. invasion and were supplied with weapons by British traders in Canada. Although the British had technically ceded the area to the United States in the Treaty of Paris in 1783 (a treaty that ignored any rights of the American Indians already living there), it was in the best interest of the British to prevent further American growth.

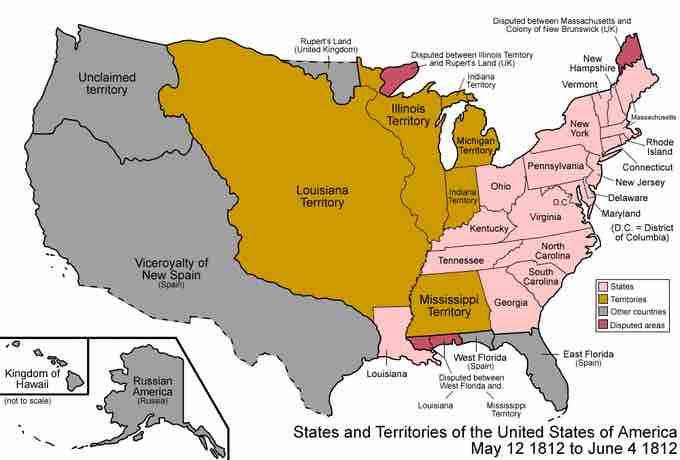

Disputed territories in the War of 1812

This map illustrates the states and territories of the United States from May 1812 to June 1812. On May 12, 1812, the federal government assigned its annexed land of West Florida to the Mississippi Territory. On June 4, 1812, to minimize confusion, the Louisiana Territory was renamed "Missouri Territory."

Economic Motivations and Tension at Home

The failure of Jefferson's embargo led to increasing pressure from Americans to go to war with England. Farmers from the West and the South were suffering from an economic depression that made them demand war. Though Jefferson wanted to avoid what he called “entangling alliances,” staying neutral proved impossible.

In the U.S. House of Representatives, a group of young Democratic-Republicans known as the "war hawks" came to the forefront in 1811. The group, led by Henry Clay from Kentucky and John C. Calhoun from South Carolina, would not tolerate British insults to American honor and advocated going to war against Great Britain. Opposition to the war came from Federalists, especially those in the Northeast, who knew war would disrupt the maritime trade on which they depended.

On June 1, 1812, President James Madison gave a speech to the U.S. Congress, recounting American grievances against Great Britain but not specifically calling for a declaration of war. After Madison's speech, Congress authorized the president to declare war against Britain by a narrow vote. The conflict formally began on June 18, 1812, when Madison signed the measure into law.