The "Compromise of 1877" refers to a purported informal, unwritten deal that settled the disputed 1876 U.S. presidential election, regarded as the second "corrupt bargain," and ended congressional ("Radical") Reconstruction. Through it, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was awarded the White House over Democrat Samuel J. Tilden on the understanding that Hayes would remove federal troops, whose support was essential to the survival of Republican state governments, from South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana. The compromise took effect even before Hayes was sworn in, as the incumbent president, Republican Ulysses S. Grant, removed the soldiers from Florida. As president, Hayes removed the remaining troops in South Carolina and Louisiana. As soon as the troops left, many white Republicans also left or became Democrats, and the "Redeemer" Democrats took control. Black Republicans felt betrayed as they lost power and were disenfranchised in the coming decades.

The Disputed Election

The need for a compromise was suggested by the congressional disagreement about the electoral proceedings. Tilden had won the popular vote by almost a quarter of a million votes, but he did not have a clear Electoral College majority. He received 184 uncontested electoral votes, while Hayes received 165, with both sides claiming the remaining 20 (4 from Florida, 8 from Louisiana, 7 from South Carolina, and 1 from Oregon). A total of 185 votes constituted an Electoral College majority; hence, Tilden needed only one of the disputed votes, while Hayes needed all twenty. The election dispute gave rise to a constitutional crisis. Many Democrats who believed that they had been cheated threatened, "Tilden or Blood!" Congressman Henry Watterson of Kentucky declared that an army of 100,000 men was prepared to march on Washington if Tilden was denied the presidency. Because the Constitution did not explicitly indicate how Electoral College disputes were to be resolved, Congress was forced to consider other methods to settle the crisis. Many Democrats argued that Congress as a whole should determine which certificates to count. However, the chances that this method would result in a harmonious settlement were slim, as the Democrats controlled the House, while the Republicans controlled the Senate. In late December, each House created a special committee charged with developing a mechanism to resolve the issue. The committees ultimately settled upon creating an Electoral Commission.

Subsequently, in a series of party-line votes, the Commission awarded all 20 disputed electoral votes to Hayes. Under the Electoral Commission Act, the Commission's findings were final unless overruled by both houses of Congress. Although the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives repeatedly voted to reject the Commission's decisions, the Republican-controlled Senate voted to uphold them. Thus, Hayes' victory was assured. Unable to overturn the Commission's decisions, many Democrats instead tried to obstruct them, mostly through filibuster. Some historians have argued that Democrats and Republicans reached an unwritten, "back room" agreement (the Compromise of 1877) under which the filibuster would be dropped in return for a promise to end Reconstruction. This thesis was most notably advanced by C. Vann Woodward in his 1951 book, Reunion and Reaction. Other historians, however, have argued that no such compromise existed.

Whatever "deals" may or may not have taken place, in formal legal terms, the election of 1876 was not decided by such acts, but by the official vote of Congress to accept the recommendations of the Electoral Commission Congress itself had set up as a way out of the election impasse. The expectation in setting up the committee had been that its decisions would be accepted by Congress. It was only when certain Democrats disagreed with the commission's decisions in favor of Hayes that this arrangement was jeopardized. This group threatened a filibuster (opposed by Republicans and Congressional Democratic leadership as well) that would prevent the agreed-upon vote from even taking place. Discussions of the points in the alleged "compromise" only concerned convincing key Democrats not to acquiesce in a filibuster. The very threat of a filibuster, a measure used by a minority to prevent a vote, indicates that there were already sufficient votes for accepting the commission's recommendations.

In any case, whether by a semiformal deal or simply reassurances already in line with Hayes's announced plans, talks with Southern Democrats satisfied the worries of many and, therefore, prevented a Congressional filibuster that had threatened to extend resolution of the election dispute beyond Inauguration Day 1877.

Terms of the Compromise

The purported compromise essentially stated that Southern Democrats would acknowledge Hayes as president, but only on the understanding that Republicans would meet certain demands.

The following elements are generally said to be the points of the compromise:

- The removal of all federal troops from the former Confederate States. Troops remained in only Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida, but the compromise finalized the process.

- The appointment of at least one Southern Democrat to Hayes's cabinet. (David M. Key of Tennessee became postmaster general.)

- The construction of another transcontinental railroad using the Texas and Pacific in the South (this had been part of the "Scott Plan," proposed by Thomas A. Scott, which initiated the process that led to the final compromise).

- The creation of legislation to help industrialize the South and get it back on its feet after the loss during the Civil War.

In exchange, Democrats would peacefully accept Hayes's presidency and respect the civil rights of black Americans.

In fact, in regard to the first point, Hayes had already announced his support for the restoration of "home rule," which would involve troop removal, before the election. It was also not unusual, nor unexpected, for a president, especially one so narrowly elected, to select a cabinet member favored by the other party. As for the final two points, if indeed there were any such firm agreements, they were never acted on.

The End of Reconstruction

With the removal of Northern troops, the President had no method to enforce Reconstruction, thus the Compromise of 1877 signaled the end of American Reconstruction. White Democrats controlled most of the Southern legislatures and armed militias controlled small towns and rural areas. The Democrats gained control of the Senate, and had complete control of Congress, having taken over the House in 1875. Hayes vetoed bills from the Democrats that outlawed the Republican Enforcement Acts; however, with the military underfunded, Hayes could not adequately enforce these laws. Blacks remained involved in Southern politics, particularly in Virginia, which was run by the biracial Readjuster Party. Overall, Blacks considered Reconstruction a failure because the federal government withdrew from enforcing their ability to exercise their rights as citizens.

The "corrupt bargain"

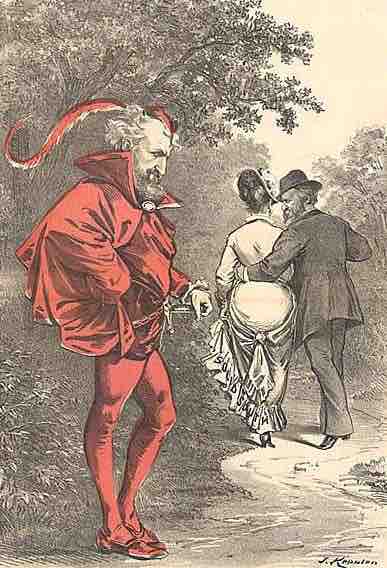

A political cartoon by Joseph Keppler depicts Roscoe Conkling as Mephistopheles, as Rutherford B. Hayes strolls off with a woman labeled as "Solid South. "