The Panic of 1873 was a worldwide depression that started when the stock market in Vienna crashed in June 1873. Unsettled markets soon spread to Berlin and throughout Europe. Three months later, the panic spread to the United States, when three major banks stopped making payments: the New York Warehouse & Security Company on September 8; Kenyon, Cox, & Co. on September 13; and the largest bank, Jay Cooke & Company, on September 18. On September 20, the New York Stock Exchange shut down for 10 days. All of these events created a depression that lasted five years in the United States, ruined thousands of businesses, depressed daily wages by 25 percent from 1873 to 1876, and brought the unemployment rate up to 14 percent. Some 89 out of 364 American railroads went bankrupt.

One of the main causes of the Panic of 1873 in the United States was overexpansion in the railroad industry after the Civil War. Between 1868 and 1873, 33,000 miles of new track were laid across the country. Much of the craze in railroad investment was driven by government land grants and subsidies to the railroads. At that time, the railroad industry was the nation's largest employer outside of agriculture, and it involved large amounts of money and risk. A large infusion of cash from speculators caused abnormal growth in the industry as well as an overbuilding of docks, factories, and ancillary facilities. At the same time, too much capital was involved in projects offering no immediate or early returns.

This unstable economic growth came at the end of a series of economic setbacks: the Black Friday panic of 1869, the Chicago fire of 1871, the outbreak of equine influenza in 1872, and demonetization of silver in 1873.

President Ulysses S. Grant, who knew little about finance, relied on bankers for advice on how to curb the panic. Secretary of Treasury William A. Richardson responded by liquidating a series of outstanding bonds. The banks, in turn, issued short-term clearing-house certificates to be used as cash. People became desperate for paper currency. Although the issuance of clearing-house certificates curbed the Panic on Wall Street, it did nothing to stop the ensuing five-year depression. Grant did nothing to prevent the panic and responded slowly after the banks crashed in September. The limited action of Secretary Richardson did little to increase confidence in the general economy.

After the Panic of 1873, Congress debated an inflationary policy to stimulate the economy and passed the Legal Tender Act, known as the "Inflation Bill," on April 14, 1874, to increase the nation's tight money supply. Many farmers and working men favored the bill, but Eastern bankers favored a veto because of their reliance on bonds and foreign investors. On April 22, 1874, after evaluating his own reasons for wanting to sign the bill, Grant unexpectedly vetoed the bill against the popular election strategy of the Republican Party because he believed it would destroy the nation's credit. Although he understood the rationale of the bill, he believed it could damage the economy in the long-run because it risked overinflation. Additionally, Eastern bankers vigorously lobbied Grant to veto the bill because of their reliance on bonds and foreign investors who did business in gold. Grant's cabinet was bitterly divided over this issue, while conservative Secretary of State Hamilton Fish threatened to resign if Grant signed the bill.

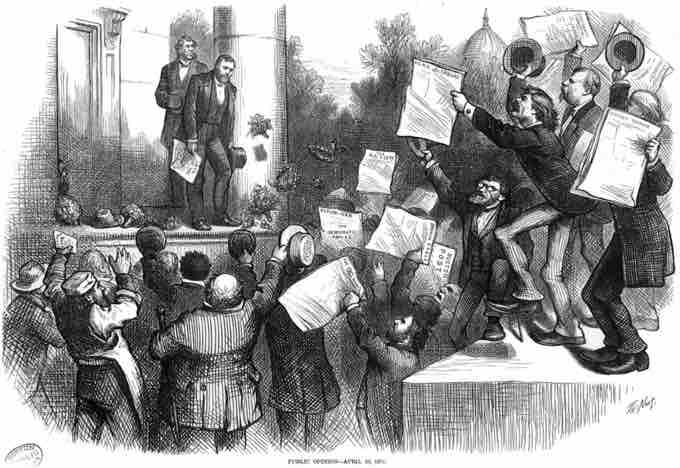

Grant vetoes the "Inflation Bill"

President Ulysses S. Grant, standing on a platform, is congratulated boisterously by an audience for vetoing the "Inflation Bill."