THE NORMANDY LANDINGS

The Normandy landings (codenamed Operation Neptune) were the landing operations on Tuesday, June 6, 1944 (known as D-Day), of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. The largest seaborne invasion in history, the operation began the liberation of German-occupied northwestern Europe from Nazi control, and contributed to the Allied victory on the Western Front.

Operation Overlord was the name assigned to the establishment of a large-scale lodgement on the Continent. The Operation Neptune was its first phase and aimed to establish a secure foothold. To gain the air superiority needed to ensure a successful invasion, the Allies undertook a bombing campaign (codenamed Operation Pointblank) that targeted German aircraft production, fuel supplies, and airfields. Elaborate deceptions, codenamed Operation Bodyguard, were undertaken in the months leading up to the invasion to prevent the Germans from learning the timing and location of the invasion.

The amphibious landings were preceded by extensive aerial and naval bombardment and an airborne assault—the landing of 24,000 American, British, and Canadian airborne troops shortly after midnight. Allied infantry and armored divisions began landing on the coast of France at 06:30. The target 50-mile stretch of the Normandy coast was divided into five sectors: Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword Beach. Strong winds blew the landing craft east of their intended positions, particularly at Utah and Omaha. The men landed under heavy fire from gun emplacements overlooking the beaches, and the shore was mined and covered with obstacles such as wooden stakes, metal tripods, and barbed wire, making the work of the beach-clearing teams difficult and dangerous. Casualties were heaviest at Omaha, with its high cliffs. At Gold, Juno, and Sword, several fortified towns were cleared in house-to-house fighting, and two major gun emplacements at Gold were disabled using specialized tanks.

D-Day: The Normandy Invasion

A LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel) from the U.S. Coast Guard-manned USS Samuel Chase disembarks troops of the U.S. Army's First Division on the morning of June 6, 1944 (D-Day) at Omaha Beach.

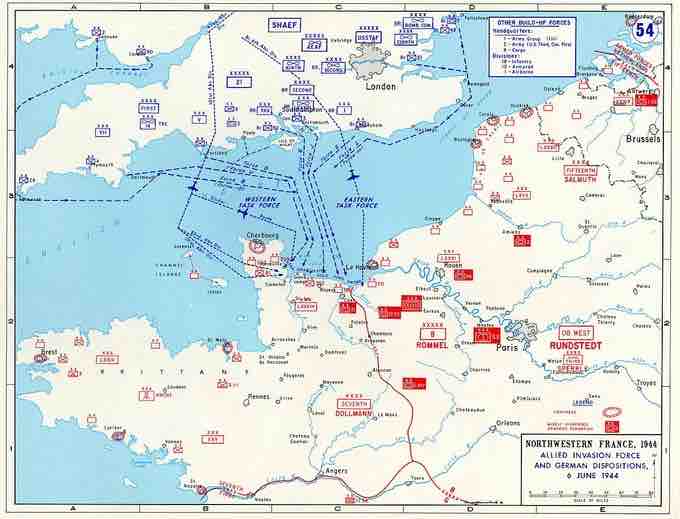

Map of Allied Invasion, D-Day

Allied invasion plans and German positions in Normandy.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). General Bernard Montgomery was named as commander of the 21st Army Group, which comprised all of the land forces involved in the invasion. The Allies failed to achieve any of their goals on the first day. Carentan, St. Lô, and Bayeux remained in German hands, and Caen, a major objective, was not captured until 21 July. Only two of the beaches (Juno and Gold) were linked on the first day, and all five beachheads were not connected until 12 June; however, the operation gained a foothold which the Allies gradually expanded over the coming months. Eventually, thirty-nine Allied divisions would be committed to the Battle of Normandy: twenty-two American, twelve British, three Canadian, one Polish, and one French, totaling over a million troops, all under overall British command.

COORDINATION WITH THE FRENCH RESISTANCE

Through the London-based État-major des Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur (French Forces of the Interior), the British Special Operations Executive orchestrated a massive campaign of sabotage to be implemented by the French Resistance. The Allies developed four plans for the Resistance to execute on D-Day. The resistance was alerted to carry out these tasks by messages personnels transmitted by the BBC's French service from London. Several hundred of these messages, which might be snatches of poetry, quotations from literature, or random sentences, were regularly transmitted, masking the few that were actually significant. In the weeks preceding the landings, lists of messages and their meanings were distributed to resistance groups. An increase in radio activity on 5 June was correctly interpreted by German intelligence to mean that an invasion was imminent or underway. However, because of the barrage of previous false warnings and misinformation, most units ignored the warning

AFTERMATH

The Normandy landings were the largest seaborne invasion in history, with nearly 5,000 landing and assault craft, 289 escort vessels, and 277 minesweepers participating. Nearly 160,000 troops crossed the English Channel on D-Day,with 875,000 men disembarking by the end of June. Allied casualties on the first day were at least 10,000, with 4,414 confirmed dead. The Germans lost 1,000 men. The Allied invasion plans had called for the capture of Carentan, St. Lô, Caen, and Bayeux on the first day, with all the beaches (other than Utah) linked with a front line 10 to 16 kilometers (6 to 10 mi) from the beaches; none of these objectives were achieved. The five bridgeheads were not connected until June 12, by which time the Allies held a front around 97 kilometers (60 mi) long and 24 kilometres (15 mi) deep. Caen, a major objective, was still in German hands at the end of D-Day and would not be completely captured until July 21. The Germans had ordered French civilians, other than those deemed essential to the war effort, to leave potential combat zones in Normandy. Civilian casualties on D-Day and D+1 are estimated at 3,000 people.

Victory in Normandy stemmed from several factors. German preparations along the Atlantic Wall were only partially finished; shortly before D-Day Erwin Rommel, German Field Marshal in command of German forces and of developing fortifications along the Atlantic Wall in anticipation of an Allied invasion, reported that construction was only 18% complete in some areas as resources were diverted elsewhere. The deceptions undertaken in Operation Fortitude were successful, leaving the Germans obligated to defend a huge stretch of coastline. The Allies achieved and maintained air supremacy, which meant that the Germans were unable to make observations of the preparations underway in Britain and were unable to interfere via bomber attacks. Transportation infrastructure in France was severely disrupted by Allied bombers and the French Resistance, making it difficult for the Germans to bring up reinforcements and supplies. Some of the opening bombardment was off-target or not concentrated enough to have any impact, but the specialized armor worked well except on Omaha, providing close artillery support for the troops as they disembarked onto the beaches. Indecisiveness and an overly complicated command structure on the part of the German high command were also factors in the Allied success.