NON-INTERVENTIONISM BEFORE WORLD WAR II

Despite the United States participation in World War I and Woodrow Wilson's active efforts to establish a new, peaceful global order, non-interventionist tendencies of US foreign policy were in full force in the aftermath of the war. The Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles, which automatically rejected the United States' membership in the League of Nations. A group of Senators known as the Irreconcilables, identifying with William Borah and Henry Cabot Lodge, two prominent Republican politicians known for their commitment to isolationism, had objected the clauses of the treaty which compelled America to come to the defense of other nations. The results of the 1920 elections, with the victory of Republican Warren G. Harding supporting American opposition to the League of Nations, proved that the isolationist stand enjoyed substantial support among ordinary Americans.

Non-interventionism or isolationism took a new turn during the Great Depression. President Herbert Hoover repeated the United States' commitment to isolationism while his successor, Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt, translated this commitment into a number of foreign policy decisions, including the introduction of Good Neighbor Policy in Latin America. The policy aimed to replace earlier military interventions of the United States in Latin America with the principle of non-intervention and non-interference in the domestic affairs of Latin America. The United States did not take any formal steps in light of such critical international events as Fascist Italy's colonization of Ethiopia, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, or the brutal Spanish Civil War.

NEUTRALITY ACTS OF THE 1930s

The post-World War I isolationism and non-interventionism in the U.S. resulted also in a number of so-called neutrality acts passed in the 1930s in response to the growing turmoil in Europe and Asia. The 1935 act imposed a general embargo on trading in arms and war materials with all parties in a war. It also declared that American citizens traveling on warring ships traveled at their own risk. The act was set to expire after six months but the 1936 act renewed its provisions and additionally forbade all loans or credits to belligerents. In January 1937, the Congress passed a joint resolution outlawing the arms trade with Spain. The Neutrality Act of 1937 included the provisions of the earlier acts, this time without expiration date, and extended them to cover civil wars as well. Further, U.S. ships were prohibited from transporting any passengers or articles to belligerents and U.S. citizens were forbidden from traveling on ships of belligerent nations.In a concession to Roosevelt, a "cash and carry" provision that had been devised by his adviser Bernard Baruch was added: the President could permit the sale of materials and supplies to belligerents in Europe as long as the recipients arranged for the transport and paid immediately in cash, with the argument that this would not draw the U.S. into the conflict. Roosevelt believed that cash and carry would aid France and Great Britain in the event of a war with Germany, since they were the only countries that controlled the seas and were able to take advantage of the provision. Finally, the Neutrality Act of 1939 was passed allowing for arms trade with belligerent nations (Great Britain and France) on a cash-and-carry basis, thus in effect ending the arms embargo. Furthermore, the Neutrality Acts of 1935 and 1937 were repealed.

THE STIMSON DOCTRINE

Following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the Stimson Doctrine was introduced. Named after Henry L. Stimson, United States Secretary of State in the Hoover Administration (1929–1933), it applied the principle of non-recognition of international territorial changes that were executed by force (ex injuria jus non oritur). The doctrine was also invoked by U.S. Under-Secretary of State Sumner Welles in a declaration of July 23, 1940, that announced non-recognition of the Soviet annexation and incorporation of the three Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—and remained the official U.S. position until the Baltic states regained independence in 1991.

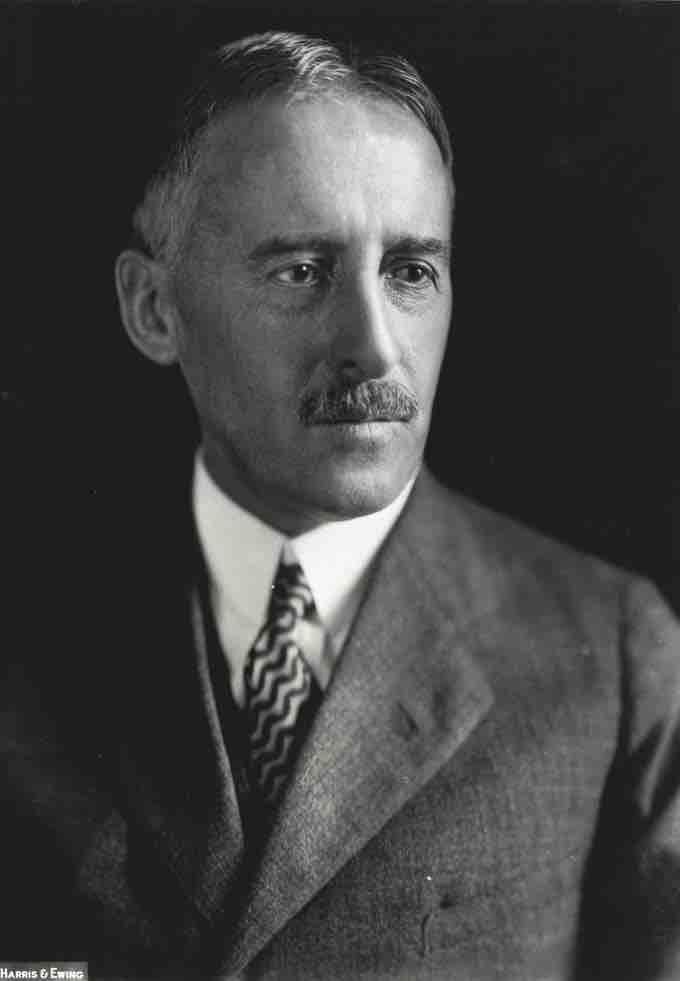

Henry Stimson in 1929; photo by Harris & Ewing.

Stimson was U.S. Secretary of State in the Hoover Administration, who proposed a doctrine based on the principle of non-recognition of international changes resulting from the use of force.

OPPOSITION TO WAR

When in 1939 Germany invaded Poland, marking the outbreak of World War II, Americans were divided over the question of non-interventionism. The basic principle of the interventionist argument was fear of German invasion. By the summer of 1940, France suffered a stunning defeat by Germans, and Britain was the only democratic enemy of Germany. In a 1940 speech, Roosevelt argued, "Some, indeed, still hold to the now somewhat obvious delusion that we … can safely permit the United States to become a lone island … in a world dominated by the philosophy of force." A national survey found that in the summer of 1940, 67% of Americans believed that a German-Italian victory would endanger the United States, that if such an event occurred 88% supported "arm[ing] to the teeth at any expense to be prepared for any trouble", and that 71% favored "the immediate adoption of compulsory military training for all young men."

However, there were still many who held on to non-interventionism. Although a minority, they were well organized, and had a powerful presence in public life and in Congress. The America First Committee (AFC), the foremost non-interventionist pressure group against the American entry into World War II, launched a petition aimed at enforcing the 1939 Neutrality Act and forcing Roosevelt to keep his pledge to keep America out of the war. They profoundly distrusted Roosevelt, arguing that he was lying to the American people. Charles Lindbergh was AFC's most prominent spokesman, who in a number of popular speeches continued his own and the organization's strong anti-war stance.

Many conservatives, especially in the Midwest, in 1939–41 favored isolationism and opposed American entry into World War II. Conservatives in the East and South were generally interventionists, as typified by Stimson. However, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 united all Americans behind the war effort, with conservatives in Congress taking the opportunity to close down many New Deal agencies.

ROOSEVELT'S THIRD TERM

In 1940, Roosevelt sought a third term, despite the long standing tradition of maximum two presidential terms. He was nominated by 946 to 147 on the first ballot. The new vice-presidential nominee was Henry Agard Wallace, a liberal intellectual who was Secretary of Agriculture. This represented Roosevelt's administration shifting to the left, as Wallace was chosen in place of conservative Texan John Nance Garner. In his campaign against Republican Wendell Willkie, Roosevelt was acutely aware of popular isolationist sentiments and stressed both his proven leadership experience and his intention to do everything possible to keep the United States out of war. Roosevelt won a comfortable victory by building strong support from labor unions, urban political machines, ethnic voters, and the traditionally Democratic South, going on to become the first United States president in American history to be elected to a full third term. The 22nd Amendment, which formally sets a term limit for election, passed in Congress in 1947, after Roosevelt's death.

Shortly after the re-election, Roosevelt delivered a radio address, in which he used the slogan "Arsenal of Democracy." Roosevelt promised to help the United Kingdom fight Nazi Germany by giving them military supplies while the United States stayed out of the actual fighting. The announcement was made a year before the attack on Pearl Harbor, at a time when Germany occupied much of Europe and threatened Britain. Roosevelt's address was "a call to arm and support" the Allies in their fight against Germany, and to a lesser extent China in their war against Japan. "The great arsenal of democracy" came to specifically reference America and its industrial machine as the primary military supplier for the Allied war effort.

Much of the Roosevelt's speech attempted to remove a sense of complacency still present in the American psyche. Roosevelt refuted the idea that America was safe because the Atlantic ocean provided a buffer from the Nazis, stating that modern technology had effectively reduced the distance across that ocean.

In 1941, the actions of the Roosevelt administration made it more and more clear that the United States was on a course to war. This policy shift, driven by the President, came in two phases. The first came with the passage of the 1939 Neutrality Act (permitting the United States to trade arms with belligerent nations, as long as these came to America to retrieve the arms, and pay for them in cash). The second phase was the Lend-Lease Act of early 1941. This act allowed the President "to lend, lease, sell, or barter arms, ammunition, food, or any 'defense article' or any 'defense information' to 'the government of any country whose defense the President deems vital to the defense of the United States.'" American public opinion supported Roosevelt's actions.