Republicanism

The colonial intellectual and political leaders in the 1760s and '70s closely read history to compare governments and their effectiveness of rule. They were especially concerned with the history of liberty in Britain, and were primarily influenced by the Country Party (which opposed the Court Party, which held power). The Country Party relied heavily on the classical republicanism of Roman heritage and celebrated the ideals of duty and virtuous citizenship in a republic. This approach produced the American political ideology of republicanism, which by 1775 had become widespread in the United States. Republicanism, based on both ancient Greek and Renaissance European thought, has been a central part of American political culture and it strongly influenced the Founding Fathers.

Republicanism and Virtue

Many leaders of the Patriot cause in the Revolution, as well as early leaders of the new United States, seemed to embody this republican ideal; these included George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. Revolutionary republicanism was centered on the ideal of limiting corruption and greed. Virtue was of the utmost importance for citizens and representatives. Revolutionaries aimed to avoid the materialism that contributed to the Roman Empire's downfall. A virtuous citizen was considered one who spurned monetary compensation and made a commitment to resist and eradicate corruption. The Republic was considered sacred; therefore it was necessary to serve the state in a truly representative way, setting aside self-interest and individual will.

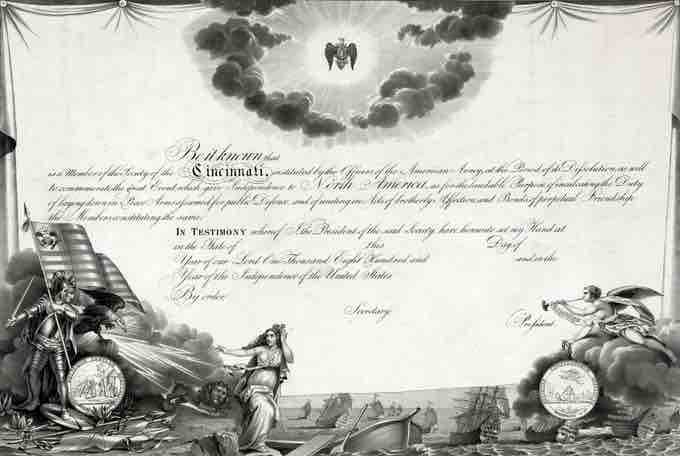

Society of the Cincinnati Membership Certificate

Widely held republican ideals led American revolutionaries to found institutions such as the Society of the Cincinnati, which was founded to preserve the ideals and camaraderie of officers who served in the American Revolution.

Republicanism required the service of people willing to give up their own interests for the common good. Virtuous citizens had to be strong defenders of liberty and challenge corruption and greed in government. Eighteenth-century US republicanism held that liberty and property were constantly threatened by corruption in the form of patronage, factions, standing armies, established churches, and monied interests.

Civic virtue became a matter of public interest and discussion during the 18th century, in part because of the American Revolutionary War. A popular opinion of the time was that republics required cultivation of specific political beliefs, interests, and habits among their citizens, and that if those habits were not cultivated, they were in danger of falling back into some type of authoritarian rule, such as a monarchy.

American historian Gordon S. Wood, conversely, described how monarchies had various advantages. The pomp and circumstance surrounding monarchies cultivated a sense that the rulers were entitled to citizens' obedience and that they maintained order just by their presence. In contrast, in a republic, the rulers were servants of the public, so there could be no sustained coercion from them. Laws had to be obeyed for the sake of conscience, rather than fear of the ruler's wrath. In a monarchy, people might be restrained by force so as to give up their own interests in favor of their government's. In a republic, however, people must be persuaded to submit their own interests to the government, and this voluntary submission constituted the 18th century's notion of civic virtue. In the absence of such persuasion, it was believed that the government's authority would collapse, and tyranny or anarchy would be imminent.

Virtue vs. Commerce

Republicanism idealized those who owned enough property to be both independently wealthy and staunchly committed to liberty and property rights. Therefore they could serve their country in the best interest of all, rather than their personal interest or that of a particular group. It was believed that the independence that personal wealth enabled would shield people from the temptations of corruption. Independently wealthy men committed to liberty and property rights were considered most likely to possess sufficient civic virtue to safeguard a republic from the dangers of corruption.

The open question of the conflict between personal economic interest (grounded in John Locke's philosophy of liberalism) and classical republicanism troubled Americans. Jefferson and James Madison roundly denounced the Federalists for creating a national bank, which could lead to corruption and monarchism. Alexander Hamilton staunchly defended his program, arguing that national economic strength was necessary for the protection of liberty. While Jefferson never relented, Madison changed his position and spoke in favor of a national bank in 1815, which he set up in 1816.

Adams also worried that financial interests could conflict with republican duty. He was especially suspicious of banks. To Adams, history taught that "the Spirit of Commerce... is incompatible with that purity of Heart, and Greatness of soul which is necessary for a happy Republic." However, so much of that spirit of commerce had already infected the United States. Adams noted that, in New England: "Even the Farmers and Tradesmen are addicted to Commerce." As a result, there was "a great Danger that a Republican Government would be very factious and turbulent there."

Voting in the 18th Century

The 18th-century United States had the widest franchise of any nation of the world. However, it was a form of society at that time. Property gave the adult white male "a stake in society, made him responsible, worthy of a voice." Enough taxable property and the right religion made him further eligible to hold office. Compared with other societies of the time, many could vote because most property was held as family farms. States also counted slaves as property for voter-qualification purposes. Three states already favored abolishing property requirements. To allow all states their own rules of suffrage, the Constitution was written with no property requirements for voting.