The Articles of Confederation were an agreement among the 13 founding states, legally establishing the United States of America as a confederation of sovereign states and serving as its first constitution. Though they are influential even to this day, the Articles created a weak government that ultimately was replaced in 1789 by the United States Constitution.

Articles of Confederation

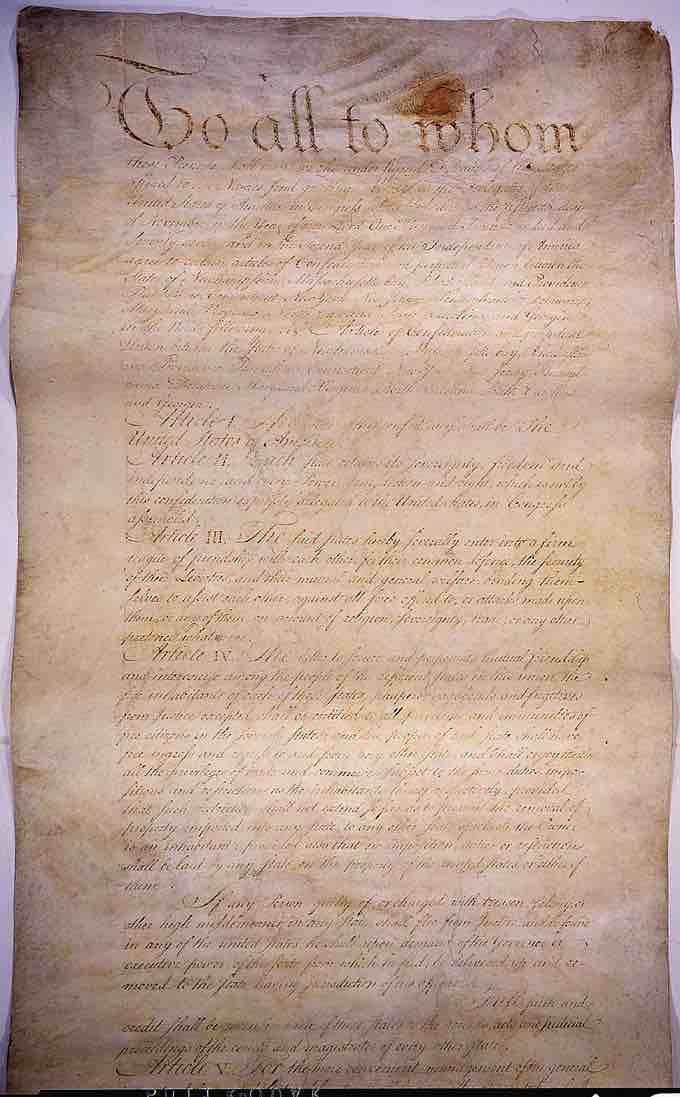

The Articles of Confederation, ratified in 1781.

Background and Context

The Articles of Confederation, which established a "firm league" among the 13 free and independent states, constituted an international agreement to set up central institutions for conducting vital domestic and foreign affairs. Congress drafted and passed the Articles in November 1777 and the states ratified them in 1781. Even when not yet ratified, the Articles provided domestic and international legitimacy for the Continental Congress to direct the American Revolutionary War, conduct diplomacy with Europe, print money, and deal with territorial issues and relations with Native Americans.

Limitations of the Articles

The Articles envisioned a permanent confederation of states, but granted its Congress—the only federal institution—little power to finance itself or ensure that its resolutions were enforced. They designated no president and no national court, and the central government's power was kept quite limited. Congress was denied any powers of taxation; it could only request money from the states. The states, in turn, often failed to meet these requests in full, leaving both Congress and the Continental Army chronically short of money. The states and Congress both incurred large debts during the Revolutionary War, and the federal government assumed these debts when some states failed to settle them.

Congress was also denied the power to regulate either foreign trade or interstate commerce. As a result, states maintained control over their own trade policies. By 1787, Congress had become unable to protect manufacturing and shipping. Congress' inability to encourage commerce and economic development—or to redeem the public obligations (debts) incurred during the war—significantly hindered its power.

Revision and Replacement

Outcry for a convention to revise the Articles grew louder. Alexander Hamilton was particularly vocal in arguing that a strong central government was necessary to levy taxes, pay back foreign debts, regulate trade, and generally strengthen the United States. He, along with a group of like-minded nationalists, earned President George Washington's endorsement. In May 1786, Continental Congress member Charles Pinckney of South Carolina proposed that Congress revise the Articles. His recommended changes included granting Congress power over foreign and domestic commerce and providing means for it to collect money from state treasuries.

Subsequently, at what came to be known as the Annapolis Convention, in 1786, the few state delegates in attendance endorsed a motion that called for all states to meet in Philadelphia in May 1787 to discuss ways to improve the Articles. This meeting became known as the Constitutional Convention. While its initial aim was to revise the Articles, it would eventually lead to the drafting of an entirely new Constitution.