The Colonial Middle Class

New England: Farmers, Craftsmen, Merchants

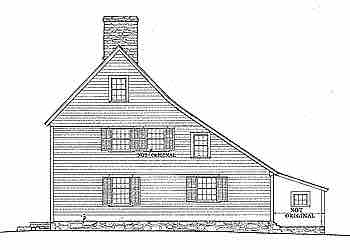

In New England, the Puritans created self-governing communities of religious congregations of farmers (yeomen) and their families. High-level politicians gave out plots of land to male settlers, or proprietors, who then divided the land among themselves. Every white man who was not an indentured servant was intended to have enough land to support a family. Many middle-class farmers lived in a style of home known as saltbox houses.

Most New England parents tried to help their sons establish farms of their own. When sons married, fathers gave them gifts of land, livestock, or farming equipment; daughters received household goods, farm animals, and/or cash. Families increased their productivity by exchanging goods and labor with each other. They loaned livestock and grazing land to one another and worked together to spin yarn, sew quilts, and shuck corn. Migration, agricultural innovation, and economic cooperation were creative measures that preserved New England's yeoman society until the 19th century.

By 1750, a variety of artisans, shopkeepers, and merchants provided services to the growing farming population. Blacksmiths, wheelwrights, and furniture makers set up shops in rural villages. There they built and repaired goods needed by farm families.

Illustration of a saltbox house

Saltbox-style homes of the middle class became popular in New England after 1650.

Mid-Atlantic Colonies

Economic patterns of the middle class in the mid-Atlantic region were very similar to those in New England, with some variations for the ethnic origins of various immigrant communities. For instance, German immigrants were renowned for their skill with animal husbandry, and unlike women in New England, women in German immigrant communities worked in the fields.

Before 1720, most colonists in the mid-Atlantic region worked with small-scale farming and paid for imported manufactures by supplying the West Indies with corn and flour. In New York, a fur pelt export trade to Europe flourished, adding additional wealth to the region. After 1720, mid-Atlantic farming was stimulated by the international demand for wheat. A massive population explosion in Europe brought wheat prices up, and by 1770, a bushel of wheat cost twice as much as it did in 1720. Farmers also expanded their production of flaxseed and corn, as flax was in high demand in the Irish linen industry and corn was in high demand in the West Indies.

In cities, shopkeepers, artisans, shipwrights, butchers, coopers, seamstresses, cobblers, bakers, carpenters, masons, and many other specialized professions made up the middle class. Wives and husbands often worked as a team and taught their children their crafts to pass skills on through the family. Many of these artisans and traders made enough money to create a modest life.

Southern Colonies

While the Southern Colonies were mainly dominated by the small class of wealthy planters in Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina, the majority of settlers were small subsistence farmers who owned family farms. About 60 percent of white Virginians, for example, were part of a broad middle class that owned substantial farms; by the second generation of settlers, death rates from malaria and other local diseases had declined so much that a stable family structure was possible. Most white men owned some land and, therefore, could vote.