Early Schooling for Girls

Public Funding

Tax-supported schooling for white girls began as early as 1767 in New England. However, because this education was optional and largely funded by public taxes, some towns proved reluctant to provide girls with educational opportunities. For example, Northampton, Massachusetts, was a late adopter because it had many wealthy families who dominated politics and society; these families did not want to pay taxes to aid poor families. Northampton assessed taxes on all households rather than just those with children and used the funds to support a grammar school to prepare boys for college. Not until after 1800 did Northampton move to educate girls with public money. In contrast, the town of Sutton, Massachusetts, was diverse in terms of social leadership and religion at an early point in its history. Sutton paid for its schools by means of taxes on households with children only, thereby creating an active constituency in favor of universal education for both white boys and girls.

Discrepancies Between Boys' and Girls' Education

In many areas, writing was taught mainly to boys and a few economically privileged girls. While white men were expected to handle "worldly affairs" and thereby were required to learn both reading and writing skills, white women often only were required to learn to read so as to ensure religious scholarship. This educational disparity between reading and writing explains why colonial women often could read but not write or sign their names.

Education and Class

The education of elite white women in Philadelphia after 1740 followed the British model developed by the gentry classes during the early nineteenth century. Rather than emphasizing ornamental aspects of women's roles, this new model encouraged women to engage in more substantive education by delving into the arts and sciences to further develop their reasoning skills. Education had the capacity to help colonial women secure their elite (economically privileged) status by giving them traits that those "inferior" to them (of lower-class backgrounds) could not easily mimic.

"Republican Motherhood" and Advancements in Education

With a growing emphasis on republicanism, women were expected to help promote these values through an idea that became known in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as "Republican Motherhood." Women were seen as having a special role in raising the next generation of children to value patriotism and to sacrifice of their own needs for the greater good of the country. Because of this, white women were permitted to receive more of an education than they previously had been allowed.

By the early nineteenth century, towns and cities were making new opportunities available for white girls and women. Abigail Adams advocated for women's education, as demonstrated in many of her letters to her husband, President John Adams. Especially influential were the writings of Lydia Maria Child, Catharine Maria Sedgwick, and Lydia Sigourney; by the 1840s, these New England writers became respected models and were advocates for improving education for females for the purpose of promoting the values of republicanism. Greater educational access included making the subjects of classical education such as mathematics and philosophy—once studied by males only—integral to curricula at public and private schools for girls.

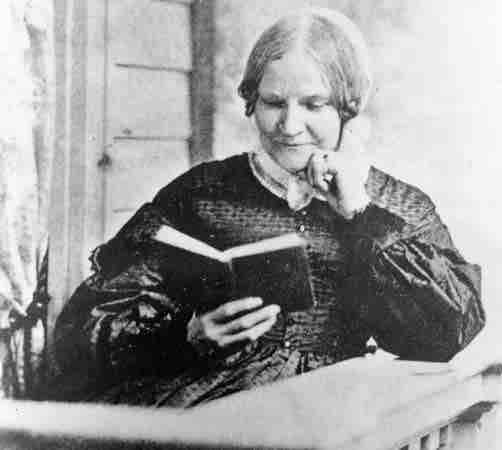

Lydia Maria Child, American activist and writer

Lydia Maria Child, pictured above, helped popularize the idea of "Republican Motherhood," which called for improved education for females.

Higher Education for Women

The first mixed-gender institute of higher education in the United States was Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, which was established in 1833. Mixed-gender classes were admitted to the preparatory department at Oberlin in 1833 and to the college department in 1837. The first four women to receive bachelor's degrees in the United States earned them at Oberlin in 1841. Later, in 1862, the first African-American woman to receive a bachelor's degree (Mary Jane Patterson) also earned it from Oberlin College. Beginning in 1844, Hillsdale College became the second college to admit mixed-gender classes to four-year degree programs.

The University of Iowa became the first coeducational public or state university in the United States in 1855, and for much of the next century, public universities (and land-grant universities in particular) would lead the way in mixed-gender higher education. There also were many private coeducational universities founded in the nineteenth century, especially west of the Mississippi River. East of the Mississippi, Cornell University admitted its first female student in 1870.

Around the same time, women-only colleges were also appearing. According to scholars Irene Harwarth, Mindi Maline, and Elizabeth DeBra, "women's colleges were founded during the mid- and late-nineteenth century in response to a need for advanced education for women at a time when they were not admitted to most institutions of higher education." Notable examples include the prestigious Seven Sisters; within this association of colleges, Vassar College is now coeducational and Radcliffe College has merged with Harvard University. Other notable women's colleges that have become coeducational include Wheaton College in Massachusetts; Ohio Wesleyan Female College in Ohio; Skidmore College, Wells College, and Sarah Lawrence College in New York state; Goucher College in Maryland; and Connecticut College.