The Eastern Woodland cultural region extended from what is now southeastern Canada, through the eastern United States, down to the Gulf of Mexico. The time in which the peoples of this region flourished is referred to as the Woodland Period. This period is known for its continuous development in stone and bone tools, leather crafting, textile manufacture, cultivation, and shelter construction. Many Woodland hunters used spears and atlatls until the end of the period when those were replaced by bows and arrows. The Southeastern Woodland hunters however, also used blowguns. The major technological and cultural advancements during this period included the widespread use of pottery and the increasing sophistication of its forms and decoration. The growing use of agriculture and the development of the Eastern Agricultural Complex also meant that the nomadic nature of many of the groups was supplanted by permanently occupied villages.

Early Woodland Period (1000–1 BCE)

The archaeological record suggests that humans in the Eastern Woodlands of North America were collecting plants from the wild by 6,000 BCE and gradually modifying them by selective collection and cultivation. In fact, the eastern United States is one of 10 regions in the world to become an “independent center of agricultural origin.” Research also indicates that the first appearance of ceramics occurred around 2,500 BCE in parts of Florida and Georgia. What differentiates the Early Woodland period from the Archaic period is the appearance of permanent settlements, elaborate burial practices, intensive collection and horticulture of starchy seed plants, and differentiation in social organization. Most of these were evident in the southeastern United States by 1,000 BCE with the Adena culture, which is the best-known example of an early Woodland culture.

The Adena culture was centered around what is present-day Ohio and surrounding states and was most likely a number of related American Indian societies that shared burial complexes and ceremonial systems. Adena mounds generally ranged in size from 2o to 300 feet in diameter and served as burial structures, ceremonial sites, historical markers, and possibly even gathering places. The mounds provided a fixed geographical reference point for the scattered populations of people dispersed in small settlements of one to two structures. A typical Adena house was built in a circular form, 15 to 45 feet in diameter. Walls were made of paired posts tilted outward that were then joined to other pieces of wood to form a cone-shaped roof. The roof was covered with bark, and the walls were bark and/or wickerwork.

While the burial mounds created by Woodland culture peoples were beautiful artistic achievements, Adena artists were also prolific in creating smaller, more personal pieces of art using copper and shells. Art motifs that became important to many later American Indians began with the Adena. Examples of these motifs include the weeping eye and the cross and circle design. Many works of art revolved around shamanic practices and the transformation of humans into animals, especially birds, wolves, bears, and deer, indicating a belief that objects depicting certain animals could impart those animals’ qualities to the wearer or holder.

Middle Woodland Period (1–500 CE)

The beginning of this period saw a shift of settlement to the interior. As the Woodland period progressed, local and inter-regional trade of exotic materials greatly increased to the point where a trade network covered most of the eastern United States. Throughout the Southeast and north of the Ohio River, burial mounds of important people were very elaborate and contained a variety of mortuary gifts, many of which were not local. The most archaeologically certifiable sites of burial during this time were in Illinois and Ohio. These have come to be known as the Hopewell tradition.

Hopewell mounds

The Eastern Woodland cultures built burial mounds for important people such as these of the Hopewell tradition in Ohio.

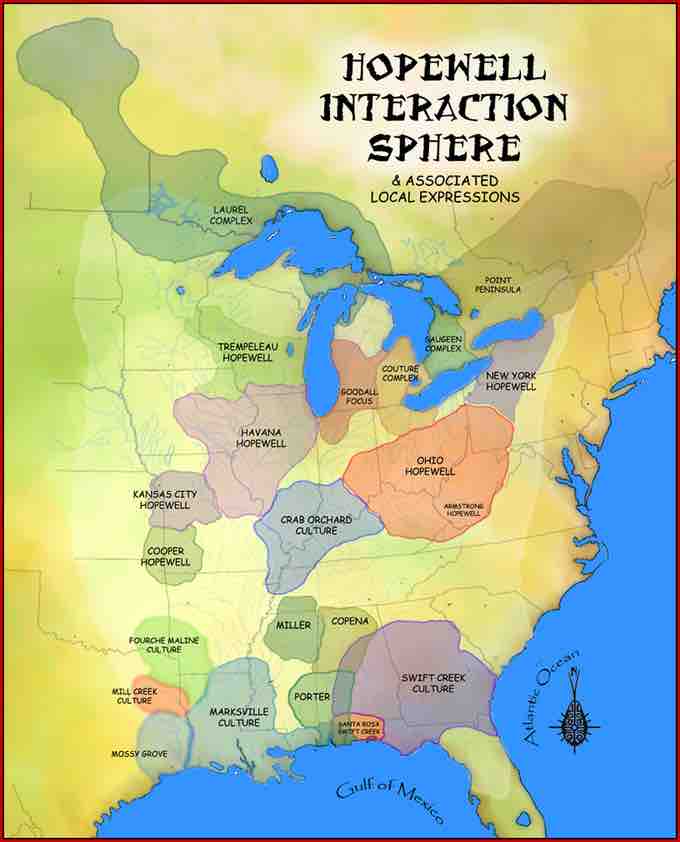

The Hopewellian peoples had leaders, but they were not powerful rulers who could command armies of soldiers or slaves. It has been posited that these cultures accorded certain families with special privileges and that these societies were marked by the emergence of “big-men,” or leaders who were able to acquire positions of power through their ability to persuade others to agree with them on matters of trade and religion. It is also likely these rulers gained influence through the creation of reciprocal obligations with other important community members. Regardless of their path to power, the emergence of big-men marked another step toward the development of the highly structured and stratified sociopolitical organization called the chiefdom, which would characterize later American Indian tribes. Due to the similarity of earthworks and burial goods, researchers assume a common body of religious practice and cultural interaction existed throughout the entire region (referred to as the "Hopewellian Interaction Sphere"). Such similarities could also be the result of reciprocal trade, obligations, or both between local clans that controlled specific territories. Clan heads were buried along with goods received from their trading partners to symbolize the relationships they had established. Although many of the Middle Woodland cultures are called Hopewellian, and groups shared ceremonial practices, archaeologists have identified the development of distinctly separate cultures during the Middle Woodland period. Examples include the Armstrong culture, Copena culture, Crab Orchard culture, Fourche Maline culture, the Goodall Focus, the Havana Hopewell culture, the Kansas City Hopewell, the Marksville culture, and the Swift Creek culture.

Hopewell Interaction Area and local expressions of the Hopewell tradition

Throughout the Southeast and north of the Ohio River, burial mounds of important people were very elaborate and contained a variety of mortuary gifts, many of which were not local. The most archaeologically certifiable sites of burial during this time were in Illinois and Ohio. These sites were constructed within the Hopewell tradition of Eastern Woodland cultures.

Ceramics during this time were thinner, of better quality, and more decorated than in earlier times. This ceramic phase saw a trend towards round-bodied pottery and lines of decoration with cross-etching on the rims.

Late Woodland Period (500–1000 CE)

The late Woodland period was a time of apparent population dispersal. In most areas, construction of burial mounds decreased drastically, as did long distance trade in exotic materials. Bow and arrow technology gradually overtook the use of the spear and atlatl, and agricultural production of the "three sisters" (maize, beans, and squash) was introduced. While full scale intensive agriculture did not begin until the following Mississippian period, the beginning of serious cultivation greatly supplemented the gathering of plants.

Late Woodland settlements became more numerous, but the size of each one was generally smaller than their Middle Woodland counterparts. It has been theorized that populations increased so much that trade alone could no longer support the communities and some clans resorted to raiding others for resources. Alternatively, the efficiency of bows and arrows in hunting may have decimated the large game animals, forcing tribes to break apart into smaller clans to better use local resources, thus limiting the trade potential of each group. A third possibility is that a colder climate may have affected food yields, also limiting trade possibilities. Lastly, it may be that agricultural technology became sophisticated enough that crop variation between clans lessened, thereby decreasing the need for trade.

In practice, many regions of the Eastern Woodlands adopted the full Mississippian culture much later than 1,000 CE. Some groups in the North and Northeast of the United States, such as the Iroquois, retained a way of life that was technologically identical to the Late Woodland until the arrival of the Europeans. Furthermore, despite the widespread adoption of the bow and arrow, indigenous peoples in areas near the mouth of the Mississippi River, for example, appear never to have made the change.