Unilateralism

Unilateralism is any doctrine or agenda that supports one-sided action. Advocates of U.S. unilateralism argue that other countries should not have "veto power" over matters of U.S. national security. Proponents of U.S. unilateralism generally believe that a multilateral institution, such as the United Nations (UN), is morally suspect because, they argue, it treats non-democratic, and even despotic, regimes as being as legitimate as democratic countries.

Two distinct schools of thought arose in the Bush Administration regarding the question of how to handle countries such as Iraq, Iran, and North Korea (the so-called "Axis of Evil" states). Secretary of State Colin Powell and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, as well as U.S. Department of State specialists, argued for what was essentially the continuation of existing U.S. foreign policy. These policies, developed after the Cold War, sought to establish a multilateral consensus for action (which would likely take the form of increasingly harsh sanctions against the problem states, summarized as the policy of containment).

The opposing view, argued by Vice President Dick Cheney, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, and a number of influential Department of Defense policy makers such as Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle, held that direct and unilateral action was both possible and justified and that America should embrace what it referred to as opportunities for democracy and security offered by its position as the sole remaining superpower. Unilateral elements were evident in the first months of Bush's presidency. Conservative Charles Krauthammer, coiner of the term "Bush Doctrine," deployed "unilateralism" in February of 2001 to refer to the president's foreign policy.

Invading Afghanistan

When it became clear that the person behind the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentegon was Osama bin Laden, a wealthy Saudi Arabian national who led the Islamic militant group al-Qaeda from Afghanistan, the full attention of the United States turned towards Central Asia and the Taliban. In his address to a joint session of Congress on September 20, President Bush had declared war on terrorism, blamed al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden for the attacks, and demanded that the radical Islamic fundamentalists who ruled Afghanistan, the Taliban, turn bin Laden over or face attack by the United States.

Bin Laden had deep roots in Afghanistan. Like many others from around the Islamic world, he had come to the country to oust the Soviet army, which invaded Afghanistan in 1979. Ironically, both bin Laden and the Taliban received material support from the United States at that time. By the late 1980s, the Soviets and the Americans had both left, although bin Laden, by that time the leader of his own organization, al-Qaeda, remained.

The Taliban refused to turn bin Laden over, and the United States began a bombing campaign in October of 2001, allying with the Afghan Northern Alliance, a coalition of tribal leaders opposed to the Taliban. U.S. air support was soon augmented by ground troops. By November of 2001, the Taliban had been ousted from power in Afghanistan’s capital of Kabul, but bin Laden and his followers had already escaped across the Afghan border to mountain sanctuaries in northern Pakistan.

The Iraq War

The Iraq War is a conflict that occurred in Iraq from March 20, 2003 to December 15, 2011, though sectarian violence still continues. Prior to the war, the governments of the United States and the United Kingdom claimed that Iraq's alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) posed a threat to their security and that of their coalition/regional allies.

Declaring War on Iraq

President George Bush, surrounded by leaders of the House and Senate, announces the Joint Resolution to Authorize the Use of United States Armed Forces Against Iraq, October 2, 2002.

Background

At the same time that the U.S. military was taking control of Afghanistan, the Bush administration was looking towards a new and larger war with the country of Iraq. Relations between the United States and Iraq had been strained ever since the Gulf War a decade earlier. Economic sanctions imposed on Iraq by the United Nations, and American attempts to foster internal revolts against President Saddam Hussein’s government, had further tainted the relationship. A faction within the Bush administration, sometimes labeled neoconservatives, believed Iraq’s recalcitrance in the face of overwhelming U.S. military superiority represented a dangerous symbol to terrorist groups around the world, recently emboldened by the dramatic success of the al-Qaeda attacks in the United States. Powerful members of this faction, including Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, believed the time to strike Iraq and solve this festering problem was right then, in the wake of 9/11. Others, like Secretary of State Colin Powell, a highly respected veteran of the Vietnam War and former chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, were more cautious about initiating combat.

The more militant side won, and the argument for war was gradually laid out for the American people. The immediate impetus to the invasion, it argued, was the fear that Hussein was stockpiling weapons of mass destruction (WMDs): nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons capable of wreaking great havoc. Hussein had in fact used WMDs against Iranian forces during his war with Iran in the 1980s, and against the Kurds in northern Iraq in 1988—a time when the United States actively supported the Iraqi dictator. Following the Gulf War, inspectors from the United Nations Special Commission and International Atomic Energy Agency had in fact located and destroyed stockpiles of Iraqi weapons.

Those arguing for a new Iraqi invasion insisted, however, that weapons still existed. President Bush himself told the nation in October of 2002 that the United States was “facing clear evidence of peril, we cannot wait for the final proof—the smoking gun—that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud.” The head of the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission, Hanx Blix, dismissed these claims. Blix argued that while Saddam Hussein was not being entirely forthright, he did not appear to be in possession of WMDs. Despite Blix’s findings and his own earlier misgivings, Powell argued in 2003 before the United Nations General Assembly that Hussein had violated UN resolutions. Much of his evidence relied on secret information provided by an informant that was later proven to be false. On March 17, 2003, the United States cut off all relations with Iraq. Two days later, in a coalition with Great Britain, Australia, and Poland, the United States began “Operation Iraqi Freedom” with an invasion of Iraq.

After investigation following the invasion, the U.S.-led Iraq Survey Group concluded that Iraq had ended its nuclear, chemical, and biological programs in 1991 and had no active programs at the time of the invasion, but that they intended to resume production if the Iraq sanctions were lifted. Although some degraded remnants of misplaced or abandoned chemical weapons from before 1991 were found, they were not the weapons which had been the one of the main arguments for the invasion.

Invading Iraq

The march into Bagdad went fairly smoothly. Soon Americans back home were watching on television as U.S. soldiers and the Iraqi people worked together to topple statues of the deposed leader Hussein around the capital. The reality, however, was far more complex. While American deaths had been few, thousands of Iraqis had died, and the seeds of internal strife and resentment against the United States had been sown. The United States was not prepared for a long period of occupation; it was also not prepared for the inevitable problems of law and order or for the violent sectarian conflicts that emerged. Thus, even though Bush proclaimed a U.S. victory in May 2003, the celebration proved premature by more than seven years.

The 2007 Surge

In 2007, President Bush increased the number of American troops in Iraq in order to provide security to Baghdad and Al Anbar Province. The surge had been developed under the working title "The New Way Forward," and it was announced in January of 2007 by Bush during a television speech. Bush ordered the deployment of more than 20,000 soldiers into Iraq and five additional brigades; he also extended the tour of most of the Army troops in country and some of the Marines already in the Anbar Province area. The President described the overall objective as establishing a "...unified, democratic federal Iraq that can govern itself, defend itself, and sustain itself, and is an ally in the War on Terror." The President stated that the surge would provide the time and conditions conducive to reconciliation among political and ethnic factions.

The surge was met with widespread disagreement and growing skepticism from politicians and the American public alike. Immediately following Bush's speech announcing the plan, Democratic politicians, including Ted Kennedy, Harry Reid, and Dennis Kucinich, called on Congress to reject the surge. More citizens began to question America's decision to go to war in the first place.

As public opinion in the United States began to favor troop withdrawals, and as Iraqi forces began to take responsibility for Iraq's security, members of the Coalition withdrew their forces. In December 2011, all U.S. personnel were withdrawn, and the United States officially declared the end of the Iraq War.

Effects of the War on Iraq

Iraq's infrastructure had already suffered severe damage during the Gulf War of 1991. Sanctions imposed by the UN after this war worsened these problems. The March 2003 invasion of Iraq resulted in the further degradation of Iraq's water, sewage, and electrical systems.

In the wake of the Iraq War in 2003, there have been numerous international efforts to rebuild the infrastructure of Iraq, many of which necessitate foreign investment. Along with the economic reform of Iraq, international aid projects have attempted to repair and upgrade Iraqi water and sewage treatment plants, electricity production, hospitals, schools, housing, and transportation systems. Much of this work has been funded by the the Coalition Provisional Authority and the Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund. At the Madrid Conference on Reconstruction, which occurred on October 23, 2003, representatives from over 25 nations met to discuss plans for rebuilding Iraq. Funds for this task were assembled at this conference as well as from other sources, and they have been administered by the United Nations and the World Bank.

While these international reconstruction efforts have produced some successes, problems have also emerged. These include inadequate security, pervasive corruption, insufficient funding, and poor coordination between international agencies and local communities. Many critics suggest that the efforts have been hampered by the international community's poor understanding of Iraq as a nation. Many have criticized private contractors for not delivering the services they promised. It has been suggested that more Iraqis, rather than Americans, should be involved in the rebuilding of Iraq.

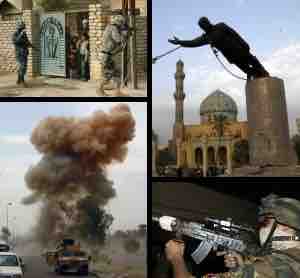

The Iraq War

Clockwise, starting at top left: a joint patrol in Samarra; the toppling of the Saddam Hussein statue in Firdos Square; an Iraqi Army soldier readies his rifle during an assault; a roadside bomb detonates in South Baghdad.