Labeling Theory on Health and Illness

Labeling theory is closely related to social-construction and symbolic-interaction analysis. Developed by sociologists during the 1960s, labeling theory holds that deviance is not inherent to an act. The theory focuses on the tendency of majorities to negatively label minorities or those seen as deviant from standard cultural norms. The theory is concerned with how the self-identity and behavior of individuals may be determined or influenced by the terms used to describe or classify them. It is associated with the concepts of self-fulfilling prophecy and stereotyping .

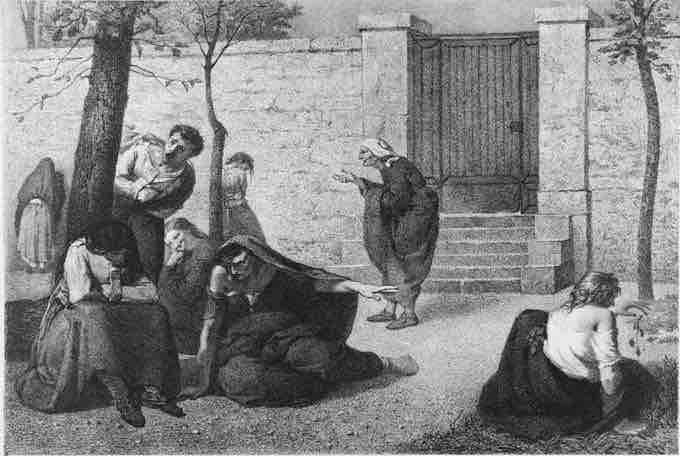

1857 Lithograph by Armand Gautier

Shows personifications of dementia, megalomania, acute mania, melancholia, idiocy, hallucination, erotic mania and paralysis in the gardens of the Hospice de la Salpêtrière. A mental disorder or mental illness is a psychological pattern, potentially reflected in behavior, that is generally associated with distress or disability, and which is not considered part of normal development of a person's culture.

The social construction of deviant behavior plays an important role in the labeling process that occurs in society. This process involves not only the labeling of criminally deviant behavior—behavior that does not fit socially constructed norms—but also labeling that reflects stereotyped or stigmatized behavior of the "mentally ill." Hard labeling refers to those who argue that mental illness does not exist; it is merely deviance from the norms of society that cause people to believe in mental illness. Mental illnesses are socially constructed illnesses and psychotic disorders do not exist. Soft labeling refers to people who believe that mental illnesses do, in fact, exist, and are not entirely socially constructed.

Labeling theory was first applied to the term "mentally ill" in 1966 when Thomas J. Scheff published Being Mentally Ill. Scheff challenged common perceptions of mental illness by claiming that mental illness is manifested solely as a result of societal influence. He argued that society views certain actions as deviant. In order to come to terms with and understand these actions, society often places the label of mental illness on those who exhibit them. Certain expectations are placed on these individuals and, over time, they unconsciously change their behavior to fulfill them. Criteria for different mental illnesses, he believed, are not consistently fulfilled by those who are diagnosed with them because all of these people suffer from the same disorder. Criteria are simply fulfilled because the "mentally ill" believe they are supposed to act a certain way—over time, they come to do so.

Another issue involving labeling was the rise of HIV/AIDS cases among gay men in the 1980s. HIV/AIDS was labeled a disease of the homosexual and further pushed people into believing homosexuality was deviant. Even today, some people believe contracting HIV/AIDS is punishment for deviant and inappropriate sexual behaviors.

Labels, while they can be stigmatizing, can also lead those who bear them down the road to proper treatment and recovery. The label of "mentally ill" may help a person seek help, such as psychotherapy or medication. If one believes that being "mentally ill" is more than just believing one should fulfill a set of diagnostic criteria, then one would probably also agree that there are some who are labeled "mentally ill" who need help. It has been claimed that this could not happen if society did not have a way to categorize them, although there are actually plenty of approaches to these phenomena that don't use categorical classifications and diagnostic terms (for example, spectrum or continuum models). Here, people vary along different dimensions, and everyone falls at different points on each dimension.