Education reform has been pursued for a variety of specific reasons, but, generally, most reforms aim at redressing some societal ills, such as poverty-, gender-, or class-based inequities, or perceived ineffectiveness.

The idea that all children should be provided with a high level of education is a relatively recent idea, and has arisen largely in the context of Western democracy in the twentieth century. In fact, educational reform has been closely tied to efforts to promote democracy. Many students of democracy desire to improve education in order to improve the quality of governance in democratic societies. The necessity of good public education follows logically if one believes that the quality of democratic governance depends on the ability of citizens to make informed, intelligent choices, and education can improve these abilities. In the United States, for example, democratic education was promoted by Thomas Jefferson, who advocated ambitious reforms for public schooling in Virginia.

Another motivation for reform is the desire to address socioeconomic problems, which many people see as having roots in unequal access to education. Starting in the twentieth century, people have attempted to argue that small improvements in education can have large returns in such areas as health, wealth and well being. For example, in developing countries, increases in women's literacy rates were correlated with increases in women's health, and increasing primary education was correlated with increasing farming efficiencies and income. Even in developed countries, an individual's level of education may predict the type of career and level of income that person can expect to achieve.

Other education reforms have been motivated by attempts to improve the effectiveness of instruction. Many modern reforms have attempted to move away from a model of education in which a teacher lectures and delivers facts to a passive student audience. For example, M. Montessori argued that education must take into account the individual needs of each child. John Dewey suggested that effective education poses problems and puzzles that motivate children to learn.

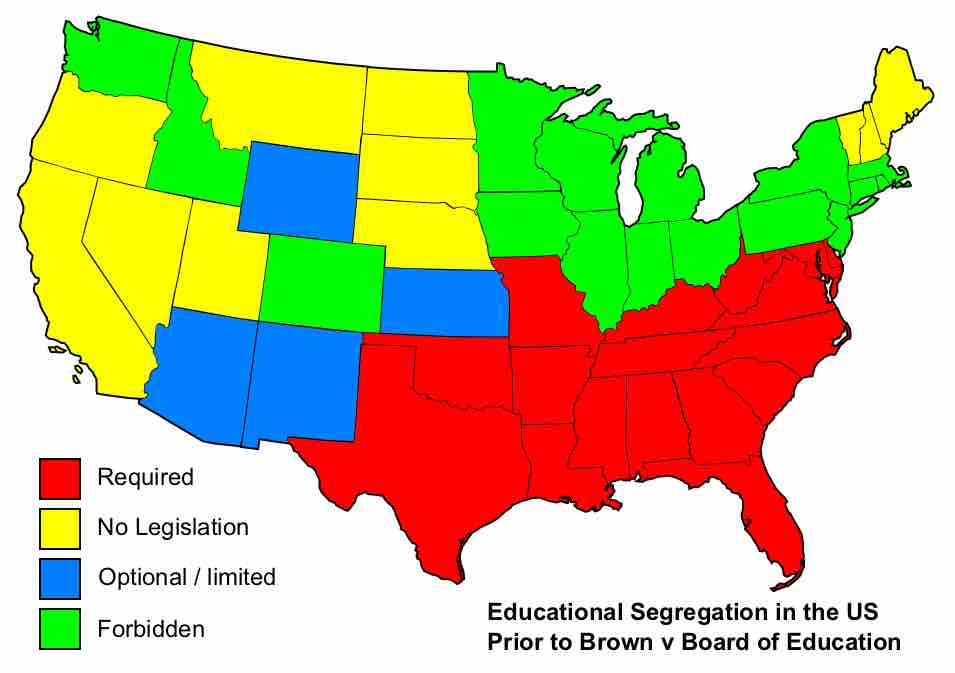

Over the years, education reform has focused on different goals. From the 1950s to the 1970s, many of the proposed and implemented reforms in U.S. education stemmed from the Civil Rights Movement and related trends; examples include ending racial segregation and busing for the purpose of desegregation, affirmative action, and banning of school prayer. In general, these reforms gave more students from more diverse backgrounds access to education.

In the 1980s, the momentum of education reform moved from the left to the right. For example, E.D. Hirsch put forth an influential attack on progressive education. He argued that progressive education failed to teach "cultural literacy," the facts, phrases, and texts that Hirsch asserted every American had once known and were still essential for decoding basic texts and maintaining communication. Hirsch's ideas remain significant through the 1990s and into the twenty-first century and are incorporated into classroom practice through textbooks and curricula published under his own imprint.

In the 1990s, most states and districts adopted Outcome-Based Education (OBE) in some form or another. Under OBE, a state would create a committee to adopt standards and choose a quantitative instrument (often, a standardized test) to assess whether the students knew the required content or could perform the required tasks. During this period, the U.S. Congress also set the standards-based National Education Goals (Goals 2000). Many of these goals were based on the principles of outcomes-based education, and not all of the goals were attained by the year 2000 as was intended. The standards-based reform movement culminated in the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. In general, OBE reforms attempt to increase accountability in education. Rather than reforming the educational process, they focus on the effects that process achieves by measuring outcomes (e.g., student achievement).

A central issue for educational reform advocates today is school choice. Debates over school choice focus on advocates' claim that school choice can promote excellence in education through competition. A highly competitive "market" for schools would eliminate the need to otherwise enforce accountability from the top down. According to advocates, schools would naturally regulate themselves and attempt to raise standards in order to attract students. Most proposals for school choice call for vouchers. Public education vouchers would permit guardians to select and pay any school, public or private, with public funds currently allocated to local public schools. In theory, children's guardians will naturally shop for the best schools, much as is already done at the college level.

Many attribute the purportedly slow pace of reform in the United States to the strength of teachers' unions. In some school districts, labor agreements with teachers' unions may restrict the ability of school systems to implement merit pay and other reforms. In general, union contracts are more restrictive in districts with high concentrations of poor and minority students.

Education Segregation in the U.S. Prior to Brown v. Board of Education

Educational reforms during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s focused on civil rights, especially desegregation and affirmative action.