Consciousness is the quality or state of being aware of an external object or something within oneself, such as thoughts, feelings, memories, or sensations. It has also been defined in the following ways: sentience, awareness, subjectivity, the ability to experience or to feel, wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood, and the executive-control system of the mind. At one time, consciousness was viewed with skepticism by many scientists, but in recent years, it has become a significant topic of research in psychology and neuroscience.

Philosophy of Consciousness

Despite the difficulty in coming to a definition, many philosophers believe that there is a broadly shared underlying intuition about what consciousness is. Philosophers since the time of Descartes and Locke have struggled to comprehend the nature of consciousness and pin down its essential properties. Issues of concern in the philosophy of consciousness include the following: whether consciousness can ever be explained mechanistically; whether non-human consciousness exists, and if so, how it can be recognized; how consciousness relates to language; whether consciousness can be understood in a way that does not require a dualistic distinction between mental and physical states or properties; and whether it may ever be possible for computers or robots to be conscious.

The Mind-Body Problem

The mind-body problem is essentially the problem of consciousness; roughly speaking, it is the question of how mental experiences arise from a physical entity. How are our mental states, beliefs, actions, and thinking related to our physical states, bodily functions, and external events, given that the body is physical and the mind is non-physical?

The first and most important philosopher to address this conundrum was René Descartes in the 17th century, and his answer was termed Cartesian dualism. The explanation behind Cartesian dualism is that consciousness resides within an immaterial domain he called res cogitans (the realm of thought), in contrast to the domain of material things, which he called res extensa (the realm of extension). He suggested that the interaction between these two domains occurs inside the brain. He further suggested the pineal glad as the point of interaction, but was later challenged several times on this claim. These challenges sparked some key initial research on consciousness, which we will discuss shortly.

Early Ideas on Consciousness

For over 2000 years, questions surrounding human consciousness—such as how the everyday inner workings of our brains give rise to a single cohesive reality and a sense of an individual self—have been baffling philosophers from Plato to Descartes. Descartes, as previously mentioned, is noted for his dualist theory of consciousness, in which the physical body is separate from the immaterial mind. He also gave us the most famous summary of human consciousness: "I think, therefore I am.”

The historical materialism of Karl Marx rejects the mind-body dichotomy, and holds that consciousness is engendered by the material contingencies of one's environment. John Locke, another early philosopher, claimed that consciousness, and therefore personal identity, are independent of all substances. He pointed out that there is no reason to assume that consciousness is tied to any particular body or mind, or that consciousness cannot be transferred from one body or mind to another.

American psychologist William James compared consciousness to a stream—unbroken and continuous despite constant shifts and changes. While the focus of much of the research in psychology shifted to purely observable behaviors during the first half of the twentieth century, research on human consciousness has grown tremendously since the 1950s.

Current Research on Consciousness

Today, the primary focus of consciousness research is on understanding what consciousness means both biologically and psychologically. It questions what it means for information to be present in consciousness, and seeks to determine the neural and psychological correlates of consciousness. Issues of interest include phenomena such as perception, subliminal perception, blindsight, anosognosia, brainwaves during sleep, and altered states of consciousness produced by psychoactive drugs or spiritual or meditative techniques.

The majority of experimental studies assess consciousness by asking human subjects for a verbal report of their experiences. However, in order to confirm the significance of these verbal reports, scientists must compare them to the activity that simultaneously takes place in the brain—that is, they must look for the neural correlates of consciousness. The hope is to find that observable activity in a particular part of the brain, or a particular pattern of global brain activity, will be strongly predictive of conscious awareness. Several brain-imaging techniques, such as EEG and fMRI scans, have been used for physical measures of brain activity in these studies.

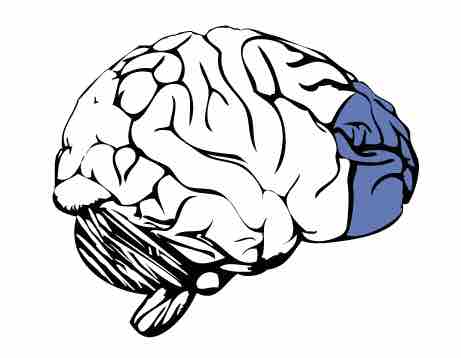

Higher brain areas are more widely accepted as necessary for consciousness to occur, especially the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in a range of higher cognitive functions collectively known as executive functions.

Prefrontal cortex

This image shows the location of the prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain heavily involved in consciousness.