Background

United States privacy law embodies several different legal concepts. One is the invasion of privacy. It is a tort based in common law allowing an aggrieved party to bring a lawsuit against an individual who unlawfully intrudes into his or her private affairs, discloses his or her private information, publicizes him or her in a false light, or appropriates his or her name for personal gain.

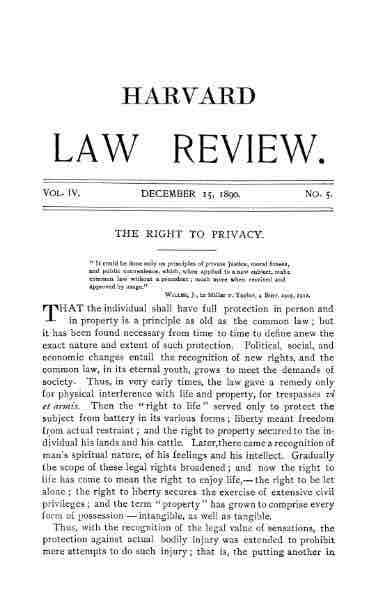

The Right to Privacy is a law review article written by Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis. It was published in the 1890 Harvard Law Review. It is one of the most influential essays in the history of American law. The article is widely regarded as the first publication in the United States to advocate a right to privacy, articulating that right primarily as a right to be left alone. It was written primarily by Louis Brandeis although credited to both men, on a suggestion of Warren based on his deep-seated abhorrence of the invasions of social privacy. William Prosser, in writing his own influential article on the privacy torts in American law, attributed the specific incident to an intrusion by journalists on a society wedding. However, in truth it was inspired by more general coverage of intimate personal lives in society columns of newspapers.

Harvard Law Review, Right to Privacy

The Right to Privacy was published at the Harvard Law Review in 15 December, 1890.

Defining the Necessity of the Right to Privacy

The authors begin the article by noting that it has been found necessary from time to time to define anew the exact nature and extent of the individual's protections of person and property. The article states that the scope of such legal rights broadens over time -- to now include the right to enjoy life -- the right to be left alone.

Then the authors point out the conflicts between technology and private life. They note that recent inventions and business methods, such as instant pictures and newspaper enterprise have invaded domestic life, and numerous mechanical devices may make it difficult to enjoy private communications.

The authors discuss a number of cases involving photography, before turning to the law of trade secrets. Finally, they conclude that the law of privacy extends beyond contractual principles or property rights. Instead, they state that it is a right against the world.

Remedies and Defenses

The authors consider the possible remedies available. They also mention the necessary limitations on the doctrine, excluding matters of public or general interest, privileged communications such as judicial testimony, oral publications in the absence of special damage, and publications of information published or consented to by the individual. They pause to note that defenses within the law of defamation -- the truthfulness of the information published or the absence of the publisher's malice -- should not be defenses. Finally, they propose as remedies the availability of tort actions for damages and possible injunctive relief.

Modern Tort Law

In the United States today, "invasion of privacy" is a commonly used cause of action in legal pleadings. Modern tort law includes four categories of invasion of privacy:

- Intrusion of solitude: physical or electronic intrusion into one's private quarters

- Public disclosure of private facts: the dissemination of truthful private information which a reasonable person would find objectionable

- False light: the publication of facts which place a person in a false light, even though the facts themselves may not be defamatory

- Appropriation: the unauthorized use of a person's name or likeness to obtain some benefits.

Constitutional basis for right to privacy

The Constitution only protects against state actors. Invasions of privacy by individuals can only be remedied under previous court decisions.

The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States ensures the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The First Amendment protects the right to free assembly, broadening privacy rights. The Ninth Amendment declares the fact that if a right is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution it does not mean that the government can infringe on that right. The Supreme Court recognized the 14th Amendment as providing a substantive due process right to privacy. This was first recognized by several Supreme Court Justices in Griswold v. Connecticut, a 1965 decision protecting a married couple's rights to contraception. It was recognized again in 1973 Roe v. Wade, which invoked the right to privacy in order to protect a woman's right to an abortion.