Freedom of the Press

Freedom of the press in the United States is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution . This clause is generally understood to prohibit the government from interfering with the printing and distribution of information or opinions. However, freedom of the press, like freedom of speech, is subject to some restrictions such as defamation law and copyright law .

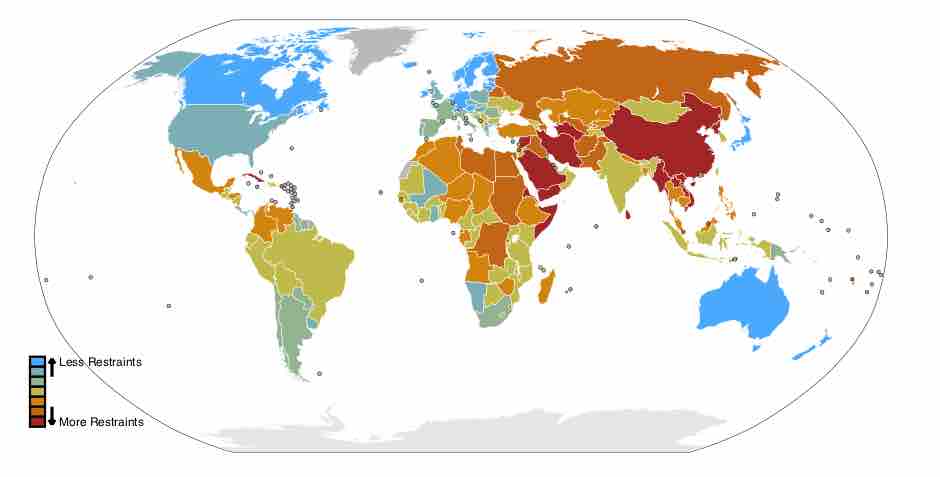

Freedom of the Press Worldwide

The First Amendment to the Constitution guarantees Americans the right to a free press. This is something that many other countries do not enjoy, as this map illustrates.

Freedom of the Press

Freedom of the press is a primary civil liberty guaranteed in the First Amendment.

In Lovell v. City of Griffin, Chief Justice Hughes defined the press as, "every sort of publication which affords a vehicle of information and opinion. " This includes everything from newspapers to blogs . The individuals, businesses, and organizations that own a means of publication are able to publish information and opinions without government interference. They cannot be compelled by the government to publish information and opinions that they disagree with. For example, the owner of a printing press cannot be required to print advertisements for a political opponent, even if the printer normally accepts commercial printing jobs.

Blogs and Free Press

Not just print media is protected under the freedom of the press; rather, all types of media, such as blogs, are protected.

Incorporation of the Freedom of the Press

In 1931, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Near v. Minnesota used the 14th Amendment to apply the freedom of the press to the states.

Violations of the Freedom of the Press in U.S. History

In 1798, not long after the adoption of the Constitution, the governing Federalist Party attempted to stifle criticism with the Alien and Sedition Acts. These restrictions on freedom of the press proved very unpopular in the end and worked against the Federalists, leading to the party's eventual demise and a reversal of the Acts.

In 1861, four newspapers in New York City were all given a presentment by a Grand Jury of the United States Circuit Court for "frequently encouraging the rebels by expressions of sympathy and agreement. " This started a series of federal prosecutions of newspapers throughout the northern United States during the Civil War which printed expressions of sympathy for southern causes or criticisms of the Lincoln Administration.

The Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 imposed restrictions on free press during wartime. In Schenck v. United States (1919), the Supreme Court upheld the laws and set the "clear and present danger" standard. In other words, the Supreme Court argued that a "clear and present danger," like wartime, justified specific free press restrictions. Congress repealed both laws in 1921. Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) revised the "clear and present danger" test to the "imminent lawless action" test, which is less restrictive.

Regulating Press and Media Content

The courts have rarely treated content-based regulation of journalism with any sympathy. In Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974), the court unanimously struck down a state law requiring newspapers criticizing political candidates to publish their responses. The state claimed that the law had been passed to ensure journalistic responsibility. The Supreme Court found that freedom, but not responsibility, is mandated by the First Amendment. So, it ruled that the government may not force newspapers to publish that which they do not desire to publish.

However, content-based regulation of television and radio has been sustained by the Supreme Court in various cases. Since there are a limited number of frequencies for non-cable television and radio stations, the government licenses them to various companies. However, the Supreme Court has ruled that the problem of scarcity does not allow the raising of a First Amendment issue. The government may restrain broadcasters, but only on a content-neutral basis. In Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation (1978), the Supreme Court upheld the Federal Communications Commission's authority to restrict the use of "indecent" material in broadcasting.

Recent Restrictions to Freedom of the Press

Some of the recent issues in restrictions of free press include: the U.S. military censoring blogs written by military personnel; the Federal Communications Commission censoring television and radio, citing obscenity; Scientology suppressing criticism, citing freedom of religion; and censoring of WikiLeaks at the Library of Congress. There has also been some controversy over the U.S. government's position that the media does not have the right to not reveal its sources. There are other critiques that claim the "war on terror" has been a pretext for further restrictions on free press.