Anatomy of the Eye

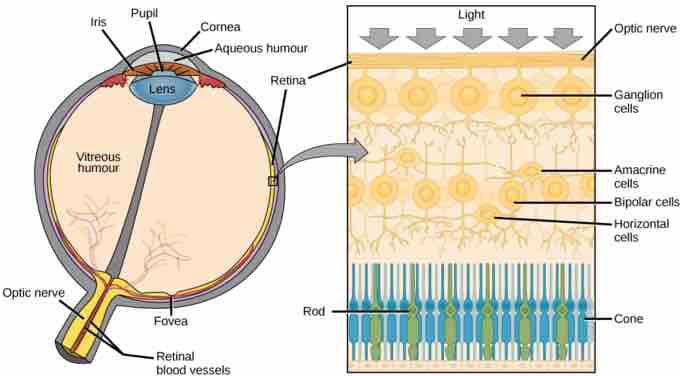

The retina, a thin layer of cells located on the inner surface of the back of the eye, consists of photoreceptive cells, which are responsible for the transduction of light into nervous impulses. However, light does not enter the retina unaltered; it must first pass through other layers that process it so that it can be interpreted by the retina .

Retina

(a) The human eye is shown in cross section. The human eye contains structures, such as the cornea, iris, lens, and fovea, that process light so it can be deciphered by the retina. Other structures like the aqueous humor and the vitreous humor help maintain the shape of the eye. (b) A blowup shows the layers of the retina. The retina contains photoreceptive cells. In the retina, light is converted into neural signals sent to the brain.

The cornea, the front transparent layer of the eye, along with the crystalline lens, refract (bend) light to focus the image on the retina. After passing through the cornea, light passes through the aqueous humour, which connects the cornea to the lens. This clear gelatinous mass also provides the corneal epithelium with nutrients and helps maintain the convex shape of the cornea. The iris, which is visible as the colored part of the eye, is a circular muscular ring lying between the lens and the aqueous humour that regulates the amount of light entering the eye. Light passes through the center of the iris, the pupil, which actively adjusts its size to maintain a constant level of light entering the eye. In conditions of high ambient light, the iris contracts, reducing the size of the pupil. In conditions of low light, the iris relaxes and the pupil enlarges .

The main function of the lens is to focus light on the retina and fovea centralis. The lens is a transparent, convex structure located behind the cornea. On the other side of the lens is the vitreous humour, which lets light through without refraction, maintains the shape of the eye, and suspends the delicate lens. The lens focuses and re-focuses light as the eye rests on near and far objects in the visual field. The lens is operated by muscles that stretch it flat or allow it to thicken, changing the focal length of light coming through to focus it sharply on the retina. With age comes the loss of the flexibility of the lens; a form of farsightedness called presbyopia results. Presbyopia occurs because the image focuses behind the retina. It is a deficit similar to a different type of farsightedness, hyperopia, caused by an eyeball that is too short. For both defects, images in the distance are clear, but images nearby are blurry. Myopia (nearsightedness) occurs when an eyeball is elongated and the image focus falls in front of the retina. In this case, images in the distance are blurry, but images nearby are clear.

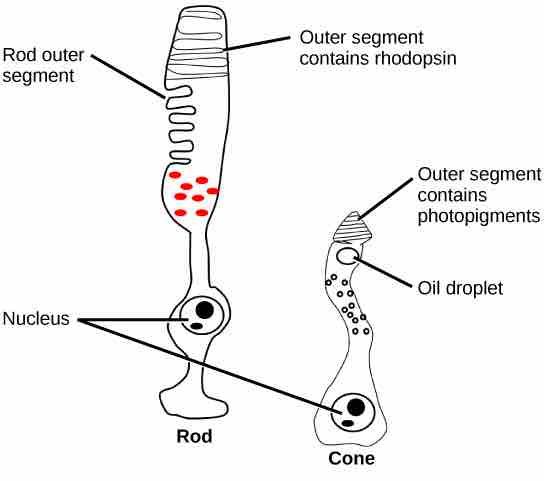

There are two types of photoreceptors in the retina: rods and cones. Both are named for their general appearance . Rods, strongly photosensitive, are located in the outer edges of the retina. They detect dim light and are used primarily for peripheral and nighttime vision. Cones, weakly photosensitive, are located near the center of the retina. They respond to bright light; their primary role is in daytime, color vision.

Rods and cones

Rods and cones are photoreceptors in the retina. Rods respond in low light and can detect only shades of gray. Cones respond in intense light and are responsible for color vision.

The fovea is the region in the center back of the eye that is responsible for acute (central) vision. The fovea has a high density of cones. When you bring your gaze to an object to examine it intently in bright light, the eyes orient so that the object's image falls on the fovea. However, when looking at a star in the night sky or other object in dim light, the object can be better viewed by the peripheral vision because it is the rods at the edges of the retina, rather than the cones at the center, that operate better in low light. In humans, cones far outnumber rods in the fovea.