Membrane potential (also transmembrane potential or membrane voltage) is the difference in electrical potential between the interior and the exterior of a biological cell. All animal cells are surrounded by a plasma membrane composed of a lipid bilayer with a variety of types of proteins embedded in it. The membrane serves as both an insulator and a diffusion barrier to the movement of ions. Ion transporter/pump proteins actively push ions across the membrane to establish concentration gradients across the membrane, and ion channels allow ions to move across the membrane down those concentration gradients, a process known as facilitated diffusion.

Virtually all eukaryotic cells (including cells from animals, plants, and fungi) maintain a nonzero transmembrane potential, usually with a negative voltage in the cell interior as compared to the cell exterior. The membrane potential has two basic functions. First, it allows a cell to function as a battery, providing power to operate a variety of "molecular devices" embedded in the membrane. Second, in electrically excitable cells such as neurons and muscle cells, it is used for transmitting signals between different parts of a cell. Signals are generated by opening or closing of ion channels at one point in the membrane, producing a local change in the membrane potential that causes electric current to flow rapidly to other points in the membrane.

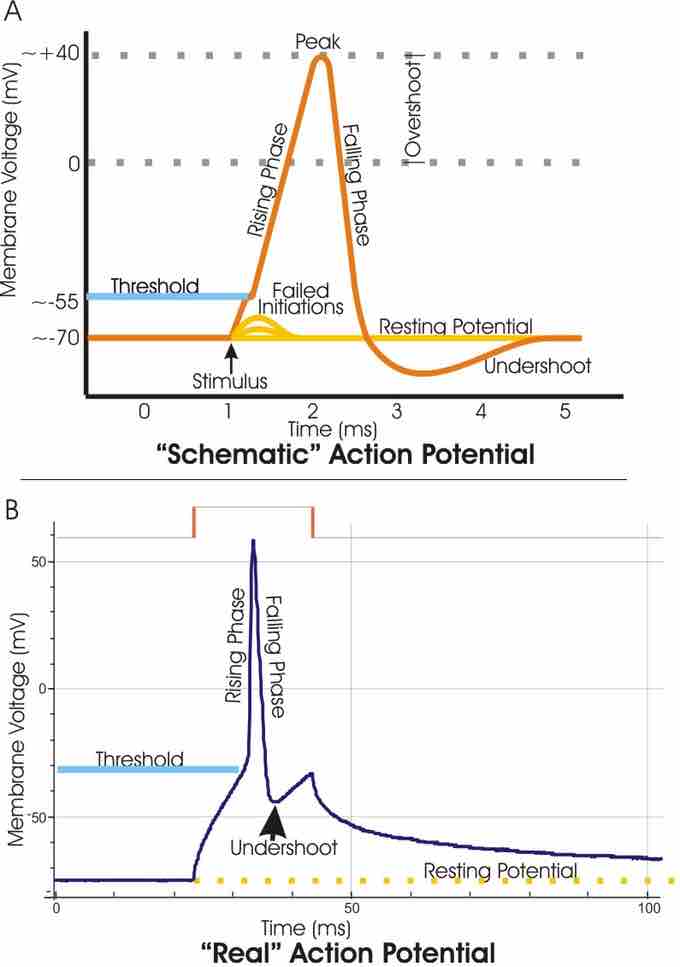

In non-excitable cells, and in excitable cells in their baseline states, the membrane potential is held at a relatively stable value, called the resting potential. For neurons, typical values of the resting potential range from –70 to –80 millivolts; that is, the interior of a cell has a negative baseline voltage of a bit less than one tenth of a volt. The opening and closing of ion channels can induce a departure from the resting potential. This is called a depolarization if the interior voltage becomes more positive (say from –70 mV to –60 mV), or a hyperpolarization if the interior voltage becomes more negative (say from –70 mV to –80 mV). The changes in membrane potential can be small or larger (graded potentials) depending on how many ion channels are activated and what type they are. In excitable cells, a sufficiently large depolarization can evoke an action potential , in which the membrane potential changes rapidly and significantly for a short time (on the order of 1 to 100 milliseconds), often reversing its polarity. Action potentials are generated by the activation of certain voltage-gated ion channels.

Action potential

A. Schematic and B. actual action potential recordings. The action potential is a clear example of how changes in membrane potential can act as a signal.