Membrane Fluidity

There are multiple factors that lead to membrane fluidity . First, the mosaic characteristic of the membrane helps the plasma membrane remain fluid. The integral proteins and lipids exist in the membrane as separate but loosely-attached molecules. The membrane is not like a balloon that can expand and contract; rather, it is fairly rigid and can burst if penetrated or if a cell takes in too much water. However, because of its mosaic nature, a very fine needle can easily penetrate a plasma membrane without causing it to burst; the membrane will flow and self-seal when the needle is extracted.

Membrane Fluidity

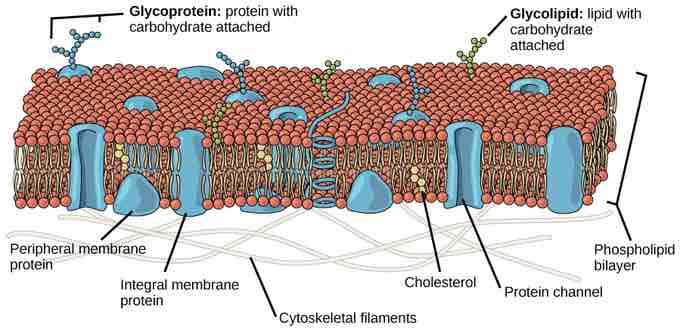

The plasma membrane is a fluid combination of phospholipids, cholesterol, and proteins. Carbohydrates attached to lipids (glycolipids) and to proteins (glycoproteins) extend from the outward-facing surface of the membrane.

The second factor that leads to fluidity is the nature of the phospholipids themselves. In their saturated form, the fatty acids in phospholipid tails are saturated with bound hydrogen atoms; there are no double bonds between adjacent carbon atoms. This results in tails that are relatively straight. In contrast, unsaturated fatty acids do not contain a maximal number of hydrogen atoms, although they do contain some double bonds between adjacent carbon atoms; a double bond results in a bend of approximately 30 degrees in the string of carbons. Thus, if saturated fatty acids, with their straight tails, are compressed by decreasing temperatures, they press in on each other, making a dense and fairly rigid membrane. If unsaturated fatty acids are compressed, the "kinks" in their tails elbow adjacent phospholipid molecules away, maintaining some space between the phospholipid molecules. This "elbow room" helps to maintain fluidity in the membrane at temperatures at which membranes with saturated fatty acid tails in their phospholipids would "freeze" or solidify. The relative fluidity of the membrane is particularly important in a cold environment. A cold environment tends to compress membranes composed largely of saturated fatty acids, making them less fluid and more susceptible to rupturing. Many organisms (fish are one example) are capable of adapting to cold environments by changing the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in their membranes in response to the lowering of the temperature.

In animals, the third factor that keeps the membrane fluid is cholesterol. It lies alongside the phospholipids in the membrane and tends to dampen the effects of temperature on the membrane. Thus, cholesterol functions as a buffer, preventing lower temperatures from inhibiting fluidity and preventing higher temperatures from increasing fluidity too much. Cholesterol extends in both directions the range of temperature in which the membrane is appropriately fluid and, consequently, functional. Cholesterol also serves other functions, such as organizing clusters of transmembrane proteins into lipid rafts.