Ionizing radiation is generally harmful, even potentially lethal, to living organisms. Although radiation was discovered in the late 19th century, the dangers of radioactivity and of radiation were not immediately recognized. The acute effects of radiation were first observed in the use of x-rays when Wilhelm Röntgen intentionally subjected his fingers to x-rays in 1895. The genetic effects of radiation, including the effects on cancer risk, were recognized much later. In 1927, Hermann Joseph Muller published research showing genetic effects.

Some effects of ionizing radiation on human health are stochastic, meaning that their probability of occurrence increases with dose, while the severity is independent of dose. Radiation-induced cancer, teratogenesis, cognitive decline, and heart disease are all examples of stochastic effects. Other conditions, such as radiation burns, acute radiation syndrome, chronic radiation syndrome, and radiation-induced thyroiditis are deterministic, meaning they reliably occur above a threshold dose and their severity increases with dose. Deterministic effects are not necessarily more or less serious than stochastic effects; either can ultimately lead to damage ranging from a temporary nuisance to death.

Quantitative data on the effects of ionizing radiation on human health are relatively limited compared to other medical conditions because of the low number of cases to date and because of the stochastic nature of some of the effects. Stochastic effects can only be measured through large epidemiological studies in which enough data have been collected to remove confounding factors such as smoking habits and other lifestyle factors. The richest source of high-quality data is the study of Japanese atomic bomb survivors.

Two pathways of exposure to ionizing radiation exist. In the case of external exposure, the radioactive source is outside (and remains outside) the exposed organism. Examples of external exposure include a nuclear worker whose hands have been dirtied with radioactive dust or a person who places a sealed radioactive source in his pocket. External exposure is relatively easy to estimate, and the irradiated organism does not become radioactive, except if the radiation is an intense neutron beam that causes activation. In the case of internal exposure, the radioactive material enters the organism, and the radioactive atoms become incorporated into the organism. This can occur through inhalation, ingestion, or injection. Examples of internal exposure include potassium-40 present within a normal person or the ingestion of a soluble radioactive substance, such as strontium-89 in cows' milk. When radioactive compounds enter the human body, the effects are different from those resulting from exposure to an external radiation source. Especially in the case of alpha radiation, which normally does not penetrate the skin, the exposure can be much more damaging after ingestion or inhalation.

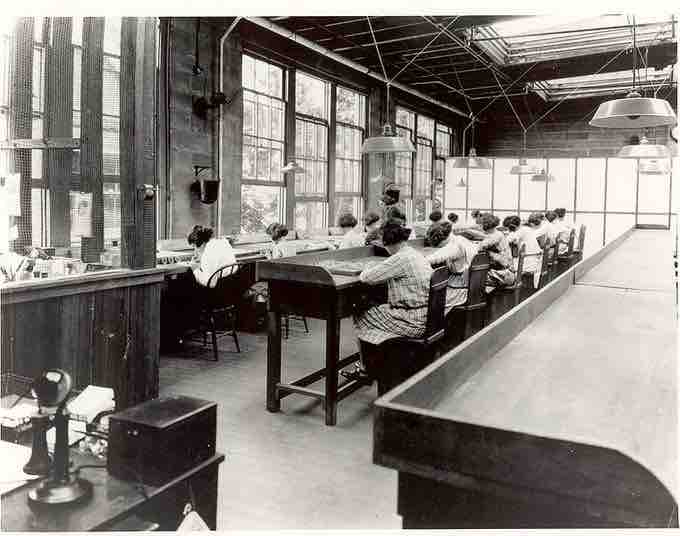

Radium Girls

Radium dial painters working in a factory