Producers and consumers trade because the exchange makes both parties better off. The benefit of exchange to producers is measured by the amount of profit – that is, the difference between the average cost of producing an item and the price received for that item. The benefit of exchange to a consumer is measured by net utility gained. This is measured by taking the difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay and the actual price they do pay. To understand this, imagine purchasing a car. You would be willing to pay up to $15,000 for a car in good condition, but you are able to buy one for only $12,000. Since you value the car at $3,000 more than you paid for it, $3,000 is the benefit that you gained from the transaction.

Economists refer to these benefits from exchange as producer and consumer surplus. Consumer surplus is the monetary gain obtained by consumers because they are able to purchase a product for a price that is less than the highest price that they would be willing to pay. Producer surplus is the amount that producers benefit by selling at a market price that is higher than the least that they would be willing to sell for.

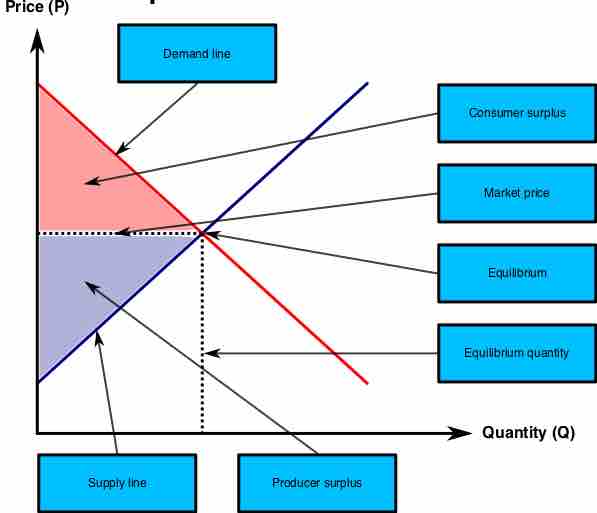

The amount of consumer and producer surplus that is gained from a transaction can be seen on a standard supply and demand graph. Consumer surplus is the area (triangular if the supply and demand curves are linear) above the equilibrium price of the good and below the demand curve. This reflects the fact that consumers would have been willing to buy a single unit of the good at a price higher than the equilibrium price, a second unit at a price below that but still above the equilibrium price, etc., yet they in fact pay just the equilibrium price for each unit they buy.

Likewise, in the supply-demand diagram, producer surplus is the area below the equilibrium price but above the supply curve. This reflects the fact that producers would have been willing to supply the first unit at a price lower than the equilibrium price, the second unit at a price above that but still below the equilibrium price, etc., yet they in fact receive the equilibrium price for all the units they sell. The sum of consumer and producer surplus is called economic, or social, surplus, and reflects the total amount of benefit received by society when consumers and producers trade.

Consumer and Producer Surplus

Consumer surplus is the area between the demand line and the equilibrium price, and producer surplus is the area between the supply line and the equilibrium price.

Exchange and Pareto Optimality

An allocation of resources is Pareto efficient when it is impossible to make any one individual better off without making at least one individual worse off. For example, imagine that two individuals prefer peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to a sandwich with only peanut butter or only jelly. A distribution in which Individual A has all of the peanut butter and individual B has all of the jelly is not Pareto efficient, because both parties would be better off if they shared their resources.

Similarly, an action that makes at least one party better off without making any individual worse off is called a Pareto improvement. Any transaction in a free market always produces a Pareto improvement because it makes consumers and/or producers better off without making either party worse off (if this were not the case, the consumer and/or the producer would refuse to participate in the transaction in the first place). It is commonly assumed that outcomes that are not Pareto efficient are to be avoided, and if a Pareto improvement is possible it should always be implemented.

One way to look at whether a transaction is a Pareto improvement is to ask whether it increases consumer or producer surplus without decreasing either party's surplus. Lowering an item's price without changing the quantity sold, for example, may increase consumer surplus, but is not a Pareto improvement because producers suffer negative consequences.