The Phillips curve shows the trade-off between inflation and unemployment, but how accurate is this relationship in the long run? According to economists, there can be no trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the long run. Decreases in unemployment can lead to increases in inflation, but only in the short run. In the long run, inflation and unemployment are unrelated. Graphically, this means the Phillips curve is vertical at the natural rate of unemployment, or the hypothetical unemployment rate if aggregate production is in the long-run level. Attempts to change unemployment rates only serve to move the economy up and down this vertical line.

Natural Rate Hypothesis

The natural rate of unemployment theory, also known as the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) theory, was developed by economists Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps. According to NAIRU theory, expansionary economic policies will create only temporary decreases in unemployment as the economy will adjust to the natural rate. Moreover, when unemployment is below the natural rate, inflation will accelerate. When unemployment is above the natural rate, inflation will decelerate. When the unemployment rate is equal to the natural rate, inflation is stable, or non-accelerating.

An Example

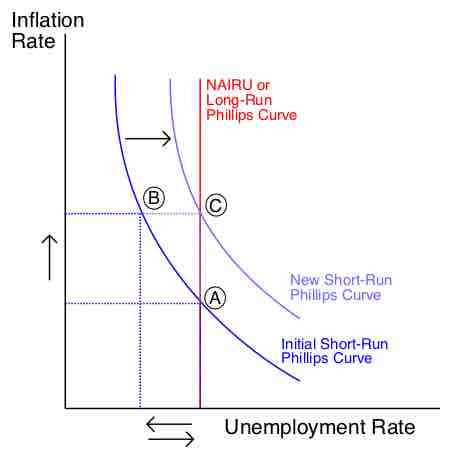

To get a better sense of the long-run Phillips curve, consider the example shown in . Assume the economy starts at point A and has an initial rate of unemployment and inflation rate. If the government decides to pursue expansionary economic policies, inflation will increase as aggregate demand shifts to the right. This is shown as a movement along the short-run Phillips curve, to point B, which is an unstable equilibrium. As aggregate demand increases, more workers will be hired by firms in order to produce more output to meet rising demand, and unemployment will decrease. However, due to the higher inflation, workers' expectations of future inflation changes, which shifts the short-run Phillips curve to the right, from unstable equilibrium point B to the stable equilibrium point C. At point C, the rate of unemployment has increased back to its natural rate, but inflation remains higher than its initial level.

NAIRU and Phillips Curve

Although the economy starts with an initially low level of inflation at point A, attempts to decrease the unemployment rate are futile and only increase inflation to point C. The unemployment rate cannot fall below the natural rate of unemployment, or NAIRU, without increasing inflation in the long run.

The reason the short-run Phillips curve shifts is due to the changes in inflation expectations. Workers, who are assumed to be completely rational and informed, will recognize their nominal wages have not kept pace with inflation increases (the movement from A to B), so their real wages have been decreased. As such, in the future, they will renegotiate their nominal wages to reflect the higher expected inflation rate, in order to keep their real wages the same. As nominal wages increase, production costs for the supplier increase, which diminishes profits. As profits decline, suppliers will decrease output and employ fewer workers (the movement from B to C). Consequently, an attempt to decrease unemployment at the cost of higher inflation in the short run led to higher inflation and no change in unemployment in the long run.

The NAIRU theory was used to explain the stagflation phenomenon of the 1970's, when the classic Phillips curve could not. According to the theory, the simultaneously high rates of unemployment and inflation could be explained because workers changed their inflation expectations, shifting the short-run Phillips curve, and increasing the prevailing rate of inflation in the economy. At the same time, unemployment rates were not affected, leading to high inflation and high unemployment.