Whether one regards inflation as a "good" thing or a "bad" thing depends very much on one's economic situation. Assuming that loans must be paid back according to a nominal amount (i.e. the borrower must pay back $100 in one year), inflation is good for borrowers and bad for lenders. When there is inflation, the value of the money borrowers pay back is less.

When inflation is expected, it has few distribution effects between borrowers and lenders. This is because the inflation rate is built in to the nominal interest rate, which is the sum of the real interest rate and expected inflation. For example, if the real cost of borrowing money is 3% and inflation is expected to be 4%, the nominal interest rate on a loan would be 7%. If the inflation rate unexpectedly jumps to 8% after the loan is made, however, then the creditor is essentially transferring purchasing power to the borrower. Since it benefits debtors and hurts creditors, in practice unexpected inflation is often a transfer of wealth from the rich to the poor .

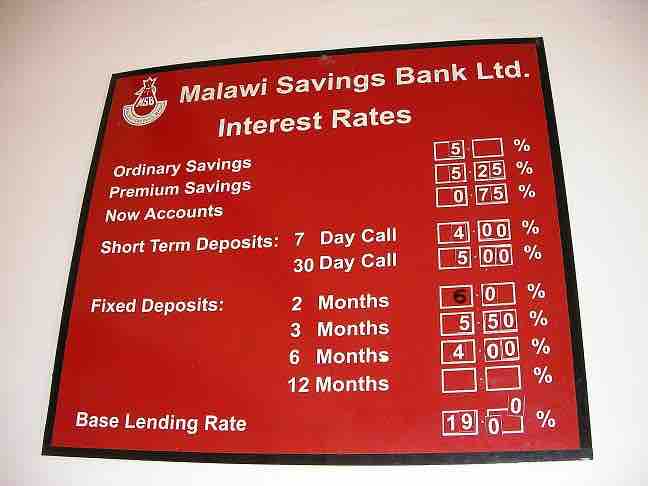

Interest Rates and Inflation

Part of the reason that lenders charge interest is to recoup the cost of inflation over time.

In general, this means that those with savings in the form of currency or bonds lose money from inflation. The lower purchasing power of money erodes the value of currency, and inflation reduces the real interest rate earned on bonds. Those with negative savings (debt) or savings in the form of stocks, however, are better off with higher inflation. Debtors find themselves paying a lower real interest rate than expected, and stocks tend to rise in value to reflect the inflation level. In demographic terms, this often manifests as a transfer from older individuals, who are wealthier and tend to hold their savings in more conservative assets such as cash and bonds, to younger individuals, who have more debt and tend to hold their savings in more aggressive assets such as stocks.