As with any statistical modeling and measuring approach, there is a great deal of complexity to capture within a finite algorithmic structure, making the accuracy and efficacy of many poverty and inequality measurements less than ideal. Inequality, poverty and economic mobility in particular have a number of measurement challenges.

Gini Index

The most popular measurement of income inequality is the Gini index, which leverages a simple scale of 0-1 to derive deviance from a given perfect equality point. If a system demonstrates a Gini index of 0, the implication is that income differences among any individuals in the population will be essentially zero, while a measurement of 1 is complete income disparity. The primary drawback to this approach is that it measures relative poverty (as opposed to absolute poverty). This criticism spans across most poverty measurement systems (Thiel entropy, the 20:20 ratio, and the Palma ratio to name a few), and ultimately implies that much of what is measured as inequality does not take into account absolute gains.

For example, if an economy were to grow by 20% over 10 years, it is perfectly possible (and indeed quite likely) that the upper 20% will capture 50% gains while the bottom 20% will only capture 10% gains. That bottom 10% (assuming inflation has been accounted for) will be gaining wealth and purchasing power in absolute terms despite the fact that the Gini index will be much worse. The Gini index still has important implications about relative inequality in this circumstance, but it neglects to point out positive gains.

Criticisms of the Poverty Line

Taking into account the problems with the Gini ratio, a concept like the poverty line does an effective job in offsetting this variability. A poverty line is the determination of a specific income level in which it is considered the absolute minimum amount of capital required for an individual or family to live (and have all necessities) over the course of one year.

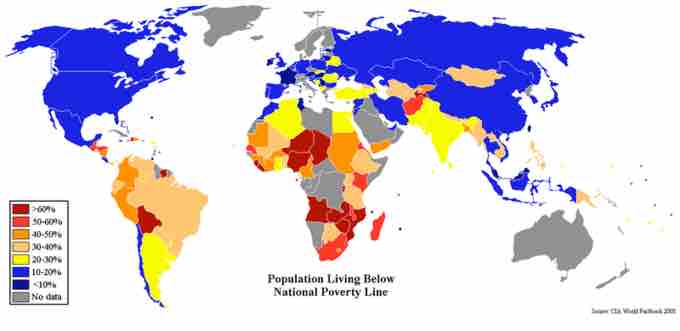

While there is great absolute value in utilizing a poverty line to determining the percentage of people still surviving on less than is considered the bare minimum, there are also drawbacks to this method as well. Looking at the , one can see that measuring the percentages of individuals under the poverty line from country to country demonstrates what appears to be a graphic for comparison. However, due to the fact that poverty lines are different in different countries (because there is no standard way in which to enforce setting and measuring the poverty line) it is not relative. As a result, there is high absolute value for each country but minimal comparative value between countries. Another prospective drawback of this method is that the poverty threshold only measures when an individual is above or below it, and not the extent to which each individual deviates. Finally, it is also important to consider less quantitative components that affect the standard of living (for example, education quality, roads, access to public transportation, access to healthcare, etc.), and thus country to country comparisons are somewhat reduced in value.

Individuals Below National Poverty Line

This graph illustrates the different percentiles of individuals under the poverty line across the world. One criticism of this method is that national poverty lines are not derived objectively in a standardized fashion, and thus there is limited value to this graphic in relative terms.

Voluntary Poverty

One interesting risk in measuring poverty is the concept of voluntary poverty, or the active pursuit of living at the absolute bare minimum. This is done as a result of lifestyle choice or religion, and is counted into poverty and inequality levels despite the fact that the individual being counted has actively pursued this place in society. While this is a somewhat unusual circumstance, it shifts the measurement of poverty in some regions (particularly those with a high population of certain beliefs or religions) higher than would be expected.