Inflation targeting is an economic policy in which a central bank publicly determines a target inflation rate and then attempts to steer actual inflation towards the target. For example, in the United States, the Federal Reserve implicitly maintains a target inflation range of 1.7%-2.0%. When inflation falls below this range, the Fed would lower interest rates and raising the money supply in order to push inflation up. Likewise, when inflation rises above the target range, the Fed would raise interest rates and decrease the money supply in order to suppress the high level of inflation . While the inflation rate and the interest rate generally have an inverse relationship, these tools are not always successful in affecting inflation - for example, in response to the 2008 financial crisis and ensuing recession, the Fed raised its target inflation level to 2% and lowered interest rates to nearly zero. This did not, however, succeed in raising inflation to 2%.

Inflation Targeting

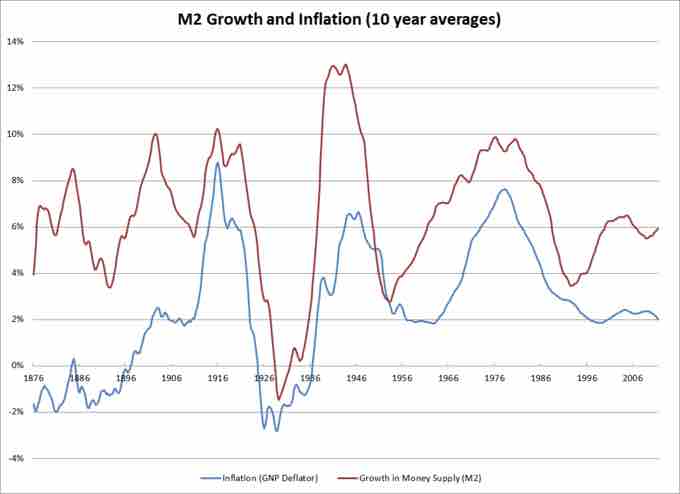

The relationship between the money supply and the inflation rate is not exact, but it suggests that a central bank can often affect inflation by adjusting the money supply through higher or lower interest rates.

Argument in Favor of Inflation Targeting

Proponents of inflation targeting argue that a volatile inflation rate has negative effects for an economy. High levels of inflation eat away at savings, increase menu costs and shoe-leather costs, discourage lending, and may create an inflationary spiral that leads to hyperinflation. Inflation targeting has been successful in keeping inflation levels low and avoiding many of these negative effects.

Further, inflation targeting is a transparent way to explain interest rate policy and to anchor consumers' expectations about future inflation. When the central bank announces an inflation target of 2%, the public knows that if inflation goes too far above or below that level, the central bank will take action. This certainty stimulates economic activity. Further, the public's expectations about inflation tend to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. When consumers expect high inflation they spend their money immediately, attempting to avoid higher future prices. This increase in demand leads to higher prices, causing more inflation. Likewise, when consumers expect deflation they tend to save their money, delaying consumption until prices fall. This decrease in demand causes producers to sell their goods at lower prices, and the cycle continues. Inflation targeting sets consumers' expectations, making a certain inflation level easier to maintain.

Arguments Against Inflation Targeting

On the other hand, some argue that the costs of inflation targeting exceed the benefits. If the rule is implemented very strictly, an inflation target could severely limit the central bank's flexibility in responding to changing economic conditions. During a recession, for example, central banks shouldn't raise the interest rate even if inflation is above the target level. Further, sometimes higher inflation is a good thing because it stimulates spending. A central bank with a strict inflation targeting rule, however, would not allow that higher inflation rate even if it were otherwise beneficial.

Others argue that, since inflation isn't necessarily coupled to any factor internal to a country's economy, inflation isn't the best variable to target. Adherents of market monetarism, for example, argue that targeting a nominal national income (nominal GDP) would be more effective than targeting inflation. Others suggest targeting long-run inflation, which takes the exchange rate into account, rather than the short-term inflation rate.