Intermolecular forces are the forces of attraction or repulsion which act between neighboring particles (atoms, molecules, or ions). These forces are weak compared to the intramolecular forces, such as the covalent or ionic bonds between atoms in a molecule. For example, the covalent bond present within a hydrogen chloride (HCl) molecule is much stronger than any bonds it may form with neighboring molecules.

Types of Attractive Intermolecular Forces

- Dipole-dipole forces: electrostatic interactions of permanent dipoles in molecules; includes hydrogen bonding.

- Ion-dipole forces: electrostatic interaction involving a partially charged dipole of one molecule and a fully charged ion.

- Instantaneous dipole-induced dipole forces or London dispersion forces: forces caused by correlated movements of the electrons in interacting molecules, which are the weakest of intermolecular forces and are categorized as van der Waals forces.

Dipole-Dipole Attractions

Dipole–dipole interactions are a type of intermolecular attraction—attractions between two molecules. Dipole-dipole interactions are electrostatic interactions between the permanent dipoles of different molecules. These interactions align the molecules to increase the attraction.

An electric monopole is a single charge, while a dipole is two opposite charges closely spaced to each other. Molecules that contain dipoles are called polar molecules and are very abundant in nature. For example, a water molecule (H2O) has a large permanent electric dipole moment. Its positive and negative charges are not centered at the same point; it behaves like a few equal and opposite charges separated by a small distance. These dipole-dipole attractions give water many of its properties, including its high surface tension.

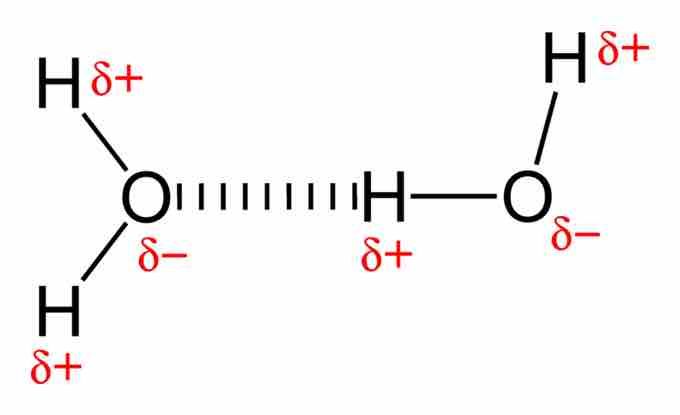

Uneven Distribution of Electrons

The permanent dipole in water is caused by oxygen's tendency to draw electrons to itself (i.e. oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen). The 10 electrons of a water molecule are found more regularly near the oxygen atom's nucleus, which contains 8 protons. As a result, oxygen has a slight negative charge (δ-). Because oxygen is so electronegative, the electrons are found less regularly around the nucleus of the hydrogen atoms, which each only have one proton. As a result, hydrogen has a slight positive charge (δ+).

Dipole-dipole attraction between water molecules

The negatively charged oxygen atom of one molecule attracts the positively charged hydrogen of another molecule.

Examples of Dipole-Dipole Interactions

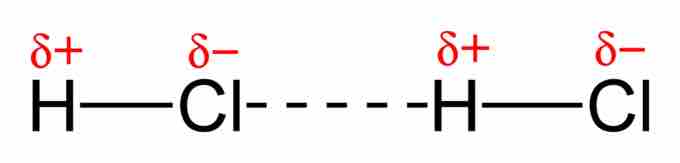

Another example of a dipole–dipole interaction can be seen in hydrogen chloride (HCl): the relatively positive end of a polar molecule will attract the relatively negative end of another HCl molecule. The interaction between the two dipoles is an attraction rather than full bond because no electrons are shared between the two molecules.

Two hydrogen chloride molecules displaying dipole-dipole interaction

The relatively negative chlorine atom is attracted to the relatively positive hydrogen atom.

Symmetrical Molecules with No Overall Dipole Moment

Molecules often contain polar bonds because of electronegativity differences but have no overall dipole moment if they are symmetrical. For example, in the molecule tetrachloromethane (CCl4), the chlorine atoms are more electronegative than the carbon atoms, and the electrons are drawn toward the chlorine atoms, creating dipoles. However, these carbon-chlorine dipoles cancel each other out because the molecular is symmetrical, and CCl4 has no overall dipole movement.

Hydrogen Bonds

Hydrogen bonds are a type of dipole-dipole interactions that occur between hydrogen and either nitrogen, fluorine, or oxygen. Hydrogen bonds are incredibly important in biology, because hydrogen bonds keep the DNA bases paired together, helping DNA maintain its unique structure.