A buffer solution usually contains a weak acid and its conjugate base. When H+ is added to a buffer, the weak acid's conjugate base will accept a proton (H+), thereby "absorbing" the H+ before the pH of the solution lowers significantly. Similarly, when OH- is added, the weak acid will donate a proton (H+) to its conjugate base, thereby resisting any increase in pH before shifting to a new equilibrium point. In biological systems, buffers prevent the fluctuation of pH via processes that produce acid or base by-products to maintain an optimal pH.

Each conjugate acid-base pair has a characteristic pH range where it works as an effective buffer. The buffering region is about 1 pH unit on either side of the pKa of the conjugate acid. The midpoint of the buffering region is when one-half of the acid reacts to dissociation and where the concentration of the proton donor (acid) equals that of the proton acceptor (base). In other words, the pH of the equimolar solution of acid (e.g., when the ratio of the concentration of acid and conjugate base is 1:1) is equal to the pKa. This represents the point in the titration that is halfway to the equivalence point. This region is the most effective for resisting large changes in pH when either acid or base is added.

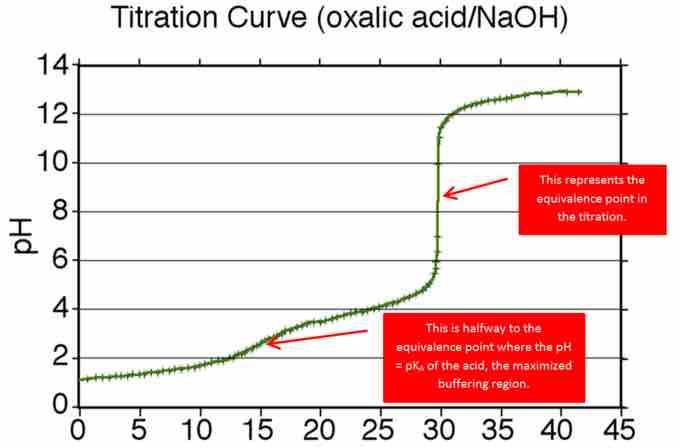

A titration curve visually demonstrates buffer capacity. The middle part of the curve is flat because the addition of base or acid does not affect the pH of the solution drastically. This is the buffer zone. However, once the curve extends out of the buffer region, it will increase tremendously when a small amount of acid or base added to the buffer system. If too much acid is added to the buffer, or if the concentration is too strong, extra protons remain free and the pH will fall sharply. This effect demonstrates the buffer capacity of the solution.

Titration curve for the addition of NaOH to oxalic acid

Shows the equivalence point and maximized buffering region for the addition of NaOH to oxalic acid.