The Benin Empire (1440–1897)

Also referred to as the Edo Empire, this empire existing in a pre-colonial African state in what is now Nigeria.

At its height, the empire extended from the shores of the Niger river through parts of the southwestern region of Nigeria. It developed an advanced artistic culture, especially known for its famous artifacts of bronze, iron, and ivory. Because of the lack of literary work during this time, Benin art provides an insight into the people, culture, traditions, and beliefs of the Empire.

Benin Art

The artwork from this period includes a range of religious objects, ceremonial weapons, masks, animal heads, figurines, busts, plaques, and other artifacts. Typically made from bronze, brass, clay, ivory, terracotta, or wood, works of art were produced mainly for the court of the Oba (king) of Benin.

Various works promoted theological and religious piety, while others narrated events and achievements (actual or mythical) which had occurred in the past. Iconic imagery depicted religious, social and cultural issues that were central to their beliefs. During the reign of the Kingdom of Benin, the characteristics of the artwork shifted from thin castings and careful treatment to thick, less defined castings and generalized features.

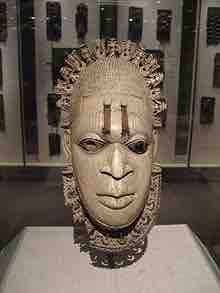

One of the most common artifacts today is the ivory mask based on Queen Idia, the mother of Oba Esigie who ruled from 1504-1550. Now commonly known as the Festac mask, it was used in 1977 as the logo of the Nigeria-hosted Second Festival of Black & African Arts and Culture ().

Edo ivory mask

Pendant ivory mask of Queen Idia (Iyoba ne Esigie (meaning: Queenmother of Oba Esigie)), court of Benin, 16th century (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Another object unique to Benin art is the Ikegobo, a cylindrical votive object. Used as a cultural marker of an individual's accomplishments, Ikegobo were dedicated to the hand, where the Beninese considered all will for wealth and success to originate from. These commemorative objects were made of brass, wood, terracotta, or clay depending on the patron's hierarchical ranking.

Portuguese Influence

The peak of the Benin art occurred in the 15th century, with the arrival of the Portuguese missionaries and traders. By that point, Benin was already highly militarized and economically developed; however, the arrival of the Portuguese catalyzed a process of even greater political and artistic development.

Because of the Benin's military strength, the European visitors were, at least for a while, unable to enslave them as they could with other peoples in Africa. Instead, a trade system was developed where the Portuguese provided the Benin with luxury items (such as coral beads, cloth and brass manillas for casting) and received paper, cloth, and Benin artwork in return. By virtue of this, the art of Benin is credited with preventing them from becoming economically dependent on the Portuguese.

As trade flourished, the Portuguese influence on the art of Benin became apparent. Traditional art began to incorporate European imagery and themes; for example, images of Portuguese sailors decorated bracelets, plaques and masks. Many famous Benin brass plaques incorporated European designs, while others illustrated the relationship between the Benin and the Portuguese .

Benin Plaque, 16th century

The background portrays the floral pattern that is characteristic of plaques made at this time, and is reflective of Portuguese influence. The image in the plaque consists of an Oba (king) surrounded by his subjects. Apart from military and political strength, the plaque illustrates the relationship between the Portuguese and the Benin traders.

In 1897, the British led the Punitive Expedition in which they ransacked the Benin kingdom and destroyed or confiscated much of their artwork. Over three thousand brass plaques were seized, and are now held in museums around the world. Known as the Benin Bronzes, they depict a variety of scenes including animals, fish, humans, and scenes of courtly life. They were cast in matching pairs (although each was individually made), and it is thought that they were originally nailed to walls and pillars in the palace as decoration.

In 1936, Oba Akenzua II began a movement to return the art to its place of origin; Nigeria bought around 50 bronzes from the British Museum between the 1950s and 1970s, and has repeatedly called for the return of the remainder.