The temple of Aphaia on the island of Aegina is an example of Archaic Greek temple design as well as of the shift in sculptural style between the Archaic and Classical periods. Aegina is a small island in the Saronic Gulf within view of Athens; in fact, Aegina and Athens were rivals. While the temple was dedicated to the local god Aphaia, the temple's pediments depicted scenes of the Trojan War to promote the greatness of the island. These scenes involve Greek heroes who fought at Troy -- Telamon and Peleus, the fathers of Ajax and Achilles. In an antagonistic move, the battle scenes on the pediments are overseen by Athena, and the temple's dedicated deity, Aphaia, does not appear on the pediment at all. While very little paint remains now, the entire pediment scene, triglyphs and metopes, and other parts of the temple would have been painted in bright colors.

Temple of Aphaia

This image shows the Temple of Aphaia as it stands today. (Marble; Aegina, Greece; ca. 500-490 BCE)

Temple Design

The Temple of Aphaia is one of the last temples with a design that did not conform to standards of the time . Its colonnade has six columns across its width and twelve columns down its length. The columns have become more widely spaced and also more slender. Both the pronaos and opisthodomos have two prostyle columns in antis and exterior access, although both lead into the temple's naos. Despite the connection between the opisthodomos and the naos, the doorway between them is much smaller than the doorway between the naos and the pronaos. As in the Temple of Hera II, there are two rows of columns on either side of the temple's interior. In this case there are five on each side, and each colonnade has two stories. A small ramp interrupts the sterobate at the center of the temple's main entrance.

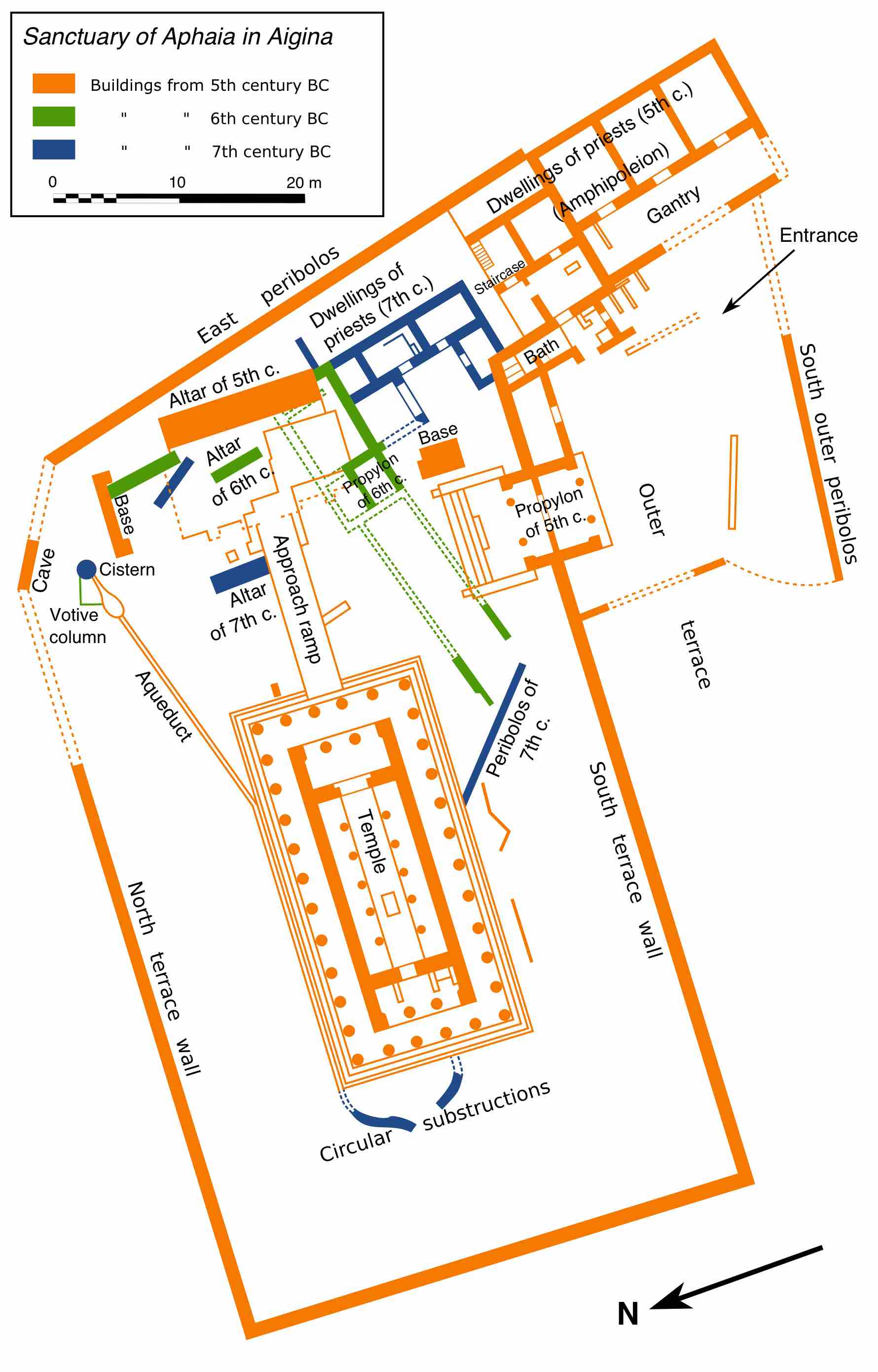

Plan of the Temple of Aphaia

Ground plan of the Temple of Aphaia and the surrounding area

The Pediments

In the case of both pediments, all figures are full-sized and carved completely in the round rather than in relief. The two battle scenes also add movement and excitement to the scene, elements not seen in earlier pedimental sculpture, which were often static and heraldic. The figures are not scaled to fit inside the shrinking space of the pediment's corners; instead, figures are properly scaled and placed in positions that allow them to fit. On both pediments, dying warriors are depicted in the corners. However, the warriors on the two pediments, carved about a decade apart, clearly depict the stylistic differences between the Archaic and Classical periods. Let's compare two examples of these dying warriors.

West Pediment

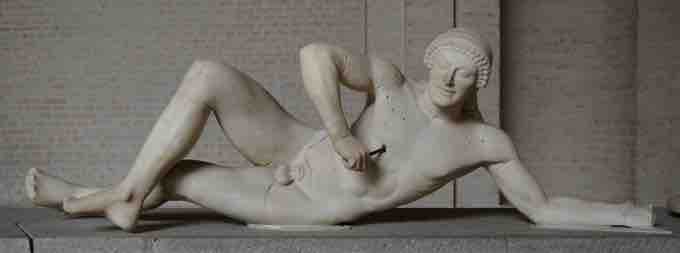

The dying warrior on the west pediment was created in 490 BCE and is a prime example of Archaic sculpture . The male warrior is depicted nude, with a muscular body that shows the Greeks' understanding of the musculature of the human body. His hair is stylized with round, geometric curls and textured patterns. But despite the naturalistic characteristics of the body, the body does not seem to react to its environment or circumstances. The warrior props himself up with an arm, and his whole body is tense, despite the fact that he has been struck by an arrow in his chest. His face, with its archaic smile, and his posture together bely all evidence that he is about to die.

Dying Warrior on the West Pediment

A dying warrior on the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia. (Marble; Aegina, Greece; ca. 490 BCE)

East Pediment

The dying warrior on the east pediment, sculpted just ten years later, in 480 BCE, is clearly carved in the new Classical style . This warrior is actually reacting to his circumstances; nearly every part of him appears to be dying. Instead of propping himself up on an arm, he hangs from his shield and attempts to support himself with his other arm. He also attempts to hold himself up with his legs, but one leg has fallen over the pediment's edge and protrudes into space. His muscles are contracted and limp, depending on which ones they are, and they seem to strain under the weight of the man as he dies. However, his mouth still has traces of the archaic smile.

Dying Warrior on the East Pediment

A dying warrior on the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia. (Marble; Aegina, Greece; ca. 480 BCE)

When we compare these two figures, the differences between the Archaic and Classical styles are evident. Despite the sculpture in the Archaic period becoming increasingly more naturalistic, the body was still stylized and idealized to create a perfect form, and the face was given a masking smile to give the statue a bit more life. While Classical sculpture is still stylized and idealistic, there is much more naturalism used, and the figures begin to react to their surroundings.