In the eleventh century BCE, the citadel centers of the Mycenaeans were abandoned and Greece fell into a period with little cultural or social progression. Signs of civilization including literacy, writing, and trade were lost and the population on mainland Greece plummeted. During the Proto-Geometric period (1050–900 BCE), painting on ceramics began to re-emerge. These vessels were only decorated with abstract geometric shapes adopted from Mycenaean pottery. Ceramicists began using the fast wheel to create vessels, which allowed for new monumental heights.

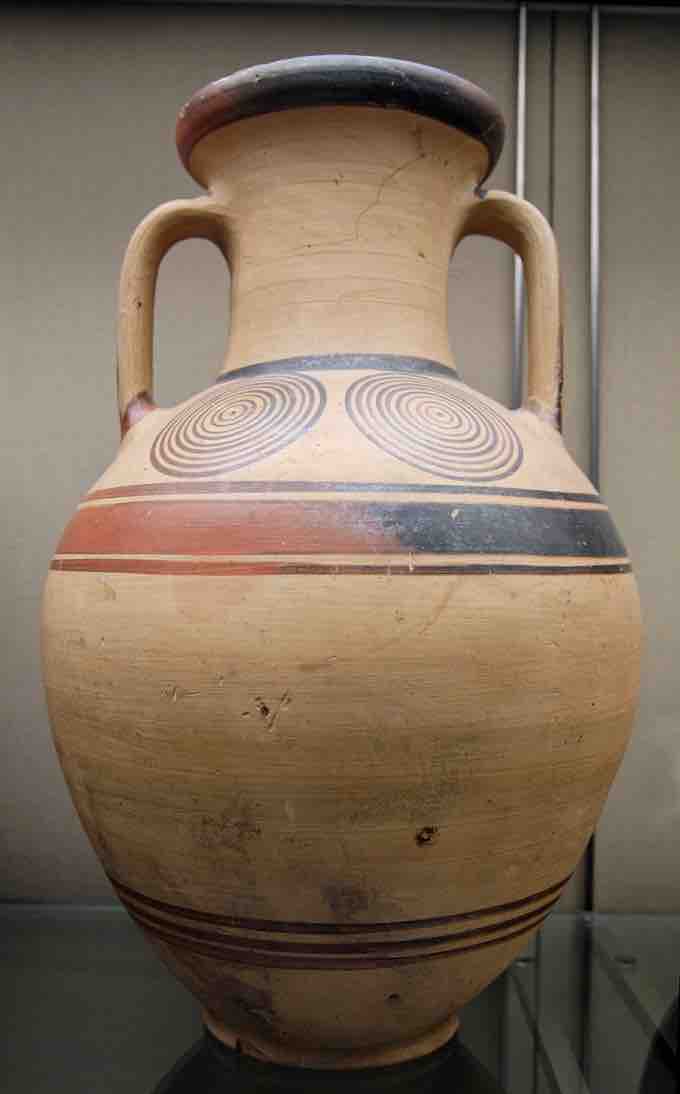

Protogeometric Amphora.

Protogeometric amphora., c. 975-950 BCE.

In the Geometric period that followed, figures once more became present on the vessel. The period lasted from 900 to 700 BCE and marked the end of the Greek Dark Ages. A new Greek culture emerged during this time. The population grew, trade began once more, and the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet for writing. Unlike the Mycenaeans, this culture was more focused on the people of the polis, which is reflected in the art of this period. The period gets its name from the reliance on geometric shapes and patterns and even their use in depicting both human and animal figures.

The city of Athens became the center for pottery production. A potter's quarter in the section of the city known as the Kerameikos was located on either side of the Dipylon Gate, one of the city's west gates. The potters lived and work inside the gate in the city, while outside the gate, along the road, was a large cemetery. In the Geometric period, monumental sized kraters and amphorae up to six feet tall were used as grave markers for the burials just outside the gate. Kraters marked male graves, while amphorae marked female graves.

The Dipylon Master, an unknown painter whose hand is recognized on many different vessels, displays the great expertise required when decorating these funerary markers. The vessels were first thrown a wheel, an important technological development at the time, before painting began. Both the Diplyon Krater and Dipylon Amphora demonstrate the main characteristics of painting during this time. For one, the entire vessel is decorated in a style known as horror vacui, a style in which the entire surface of the medium is filled with imagery. On the lip of the krater and on many registers of the amphora, is a decorative meander. This geometric motif is constructed from a single, continuous line in a repeated shape or motif.

The main scene is depicted on the widest part of the pot's body. These scenes relate to the funerary aspect of the pot and may depict mourners, a prothesis (a ritual of laying the body out and mourning), or even funerary games and processions. On the Dipylon Krater, two registers depict a processional scene, an ekphora, (the transportation of the body to the cemetery) and the prothesis . The dead man of the prothesis scene is seen on the upper register. He is laid out on a bier and mourners, distinguished by their hands tearing at their hair, surround the body. Above the body is a shroud, which the artist depicts above and not over the body in order to allow the viewer to see the entirety of the scene. On the register below, chariots and soldiers form a funerary procession. The soldiers are identified by their uniquely shaped shields. The Dipylon Amphora depicts just a prothesis in a wide a register around the pot. In both vessels, men and women are distinguished by protruding triangles on their chest or waist to represent breasts or a penis. Every empty space in these scenes is filled with geometric shapes—M's, diamonds, starbursts—demonstrating the Geometric painter's horror vacui.

Geometric Amphora

Geometric Amphora, from the Dipylon Cemetery, Athens, Greece, c. 740 BCE.

Geometric Krater

Geometric Krater. From the Dipylon Cemetery, Athens, Greece, c. 740 BCE.