Akhenaten was a pharaoh of the 18th dynasty who was known before the fifth year of his reign as Amenhotep IV. He ruled for 17 years (1353-1336 BC) and is especially noted for abandoning traditional Egyptian polytheism and introducing a relatively monotheistic worship centered on the Aten, a kind of solar deity. In the end this change was not accepted and, after his death, traditional religious practice was gradually restored. During his reign, Akhenaten built a city for Aten that is known today as Amarna, and ushered in a period of art, known as the Amarna Period. The Amarna Period is noted for its artistic style, which drastically shifted away from conventional styles of art and centered around the worship of Aten. Although the worship of Aten was completely suppressed after Akhenaten's death, the artistic legacy had a more lasting impact.

Amarna-style Painting and Sculpture

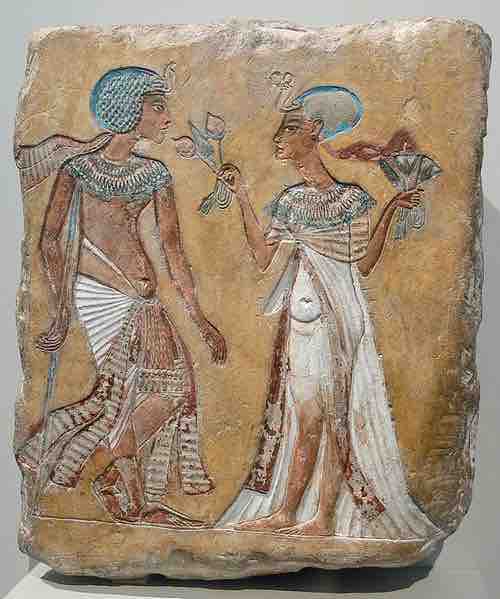

Art from this period is characterized by a sense of movement and activity in images, with busy and crowded scenes and many of the figures overlapping. The human body is portrayed more realistically, rather than idealistically, though at times depictions border on caricature. For example, many depictions of Akhenaten's body show him with wide hips, a drooping stomach, thick lips and thin arms and legs. This is a divergence from the earlier Egyptian art which shows men with perfectly chiseled bodies , and there is generally a more "feminine" quality in male figrues. Some scholars suggest that the presentation of the human body as imperfect during the Amarna period is in deference to Aten.

Artist's sketch: Walk in the Garden; limestone; New Kingdom, 18th dynasty, c. 1335 BC

A relief of a royal couple in the Armana style. The figures are thought to be Akhenaten and Nefertiti, Smenkhkare and Meritaten, or Tutankhamen and Ankhesenamun.

Sculptures from the Amarna period are set apart for their accentuation of certain features. Many works depicted important people with an elongation and narrowing of the neck, a sloping of the forehead and nose, a prominent chin, large ears and lips, spindle-like arms and calves and large thighs, stomachs, and hips . The period saw the use of sunk relief, previously used for large external reliefs, extended to small carvings and used for most monumental reliefs.

A relief portrait of Akhenaten.

Akhenaten represented in the typical Amarna period style. New Kingdom, 18th dynasty, circa 1345 B.C.

Like previous works, faces on reliefs continued to be shown exclusively in profile. The illustration of figures' hands and feet showed great detail, with fingers and toes depicted as long and slender. The skin color of both males and females was generally dark brown, in contrast to the previous tradition of depicting women with lighter skin. Along with traditional court scenes, intimate scenes were often portrayed. In a relief of Akhenaten, he is shown with his primary wife, Nefertiti, and their children in an intimate setting. His children are shrunken to appear smaller than their parents, a routine stylistic feature of traditional Egyptian art .

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their children

This relief illustrates an intimate portrait of Akhenaten and his family in the Amarna style of art.

Much of the finest work, including the famous Nefertiti bust in Berlin, was found in the studio of the second and last Royal Court Sculptor Thutmose, and is now in Berlin and Cairo, with some in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Tombs

The decoration of the tombs of non-royals was quite different from previous eras. These tombs did not feature any funerary or agricultural scenes, nor did they include the tomb occupant unless he or she was depicted with a member of the royal family. Decorations clearly worshiped the Aten, with excerpts from the Hymn to the Aten often present in the tombs; there is an absence of other gods and goddesses and no mention of Osiris or the underworld.

Architecture

Not many buildings from this period have survived the ravages of later kings, partially as they were constructed out of standard-size blocks, known as talatat, which were very easy to remove and reuse. In recent decades, restoration work on later buildings has revealed large numbers of reused blocks from the period, with the original carved faces turned inwards, greatly increasing the amount of work known from the period. Temples in Amarna did not follow the traditional Egyptian design: typically smaller, they had sanctuaries open to the sun, no closing doors, and contained a large numbers of altars.

Amarna Letters

Much of what we know of the Amarna period today comes from the discovery of the Amarna Letters. In 1887, a local woman uncovered a cache of over 300 tablets recording select diplomatic correspondence of the Pharaoh. They are predominantly written in Akkadian, the lingua franca commonly used during the Late Bronze Age of the Ancient Near East for such communication.