The assassination of Commodus in 192 CE once again plunged the Roman Empire into a year of civil war. Five generals succeeded one another until the fifth, Septimius Severus, consolidated power and managed to reign over Rome until his death from illness, 19 years later in 211 CE.

He established the Severan Dynasty that reigned until 235 CE, overseen by five different emperors. Unfortunately for Rome, the economy and the bureaucratic and administrative power of the Emperor and the Senate were declining during this time. The five Severan emperors faced great difficulties maintaining control over the empire. Their troubles demonstrate the importance of this pivotal period that ultimately led to Rome's decline.

Septimius Severus

To strengthen his claim as emperor, Septimius Severus declared himself to be the secret son of Marcus Aurelius and even had his portrait fashioned in a similar manner to him. Like Marcus Aurelius, Septimius Severus wore his beard thick and curly in the style of Greek philosophers. His portraits show him as old, but fit and without the winkles of wisdom seen in Republican veristic portraiture.

Triumphal Arches of Septimius Severus

Two triumphal arches commissioned by Septimius Severus still stand today: the first at the northwest entrance to the Roman forum, and the second on the main road leading into the city of Leptis Magna, the Roman colony in modern Libya where Septimius Severus was born. Both were erected in 203 CE and commemorate the emperor's victory over the Parthians.

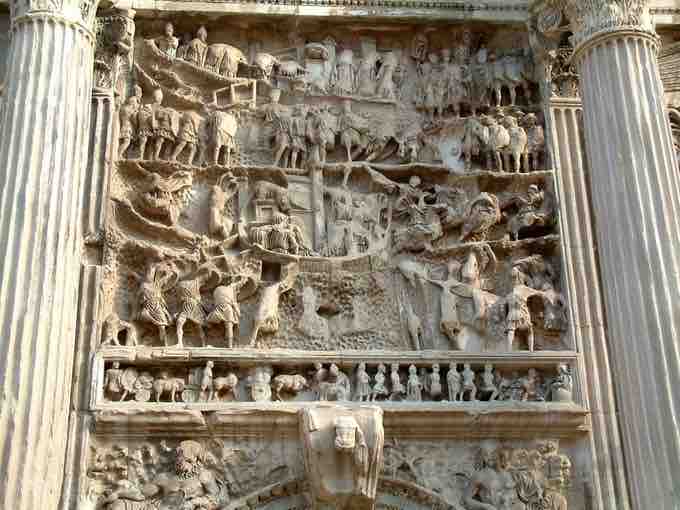

The Roman Arch of Septimius Severus recalls the triumphal arch of Augustus, also erected to honor his own victory over the Parthians. Like Augustus's arch, that of Septimius is a triple arch--the only surviving one in Rome. Decorative panels depict scenes of conquest echoing the military scenes on the Columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius. These, however, depart from the Classical style, stylistically resembling more the figures on the Column of Marcus Aurelius. The figures on the panels are carved in high relief, and each shows multiple scenes. Small friezes recounting the triumphal procession also frame the panels. Other decorative elements include winged victories in the spandrels and two sets of four columns, one on each side, framing the archways. The columns are free-standing, decorative additions to the arch. On the pedestal of each are reliefs of Romans leading captive Parthians away. This arch visually recalls the triumphal arches of the past that stood in the Roman Forum and expresses the continuity of Septimius Severus's imperial rule and the momentum of the empire.

Detail of the Arch of Septimius Severus

Detail of a panel relief.

The Roman Arch of Septimius Severus

Rome, Italy.

The Arch of Septimius Severus at Leptis Magna is architecturally distinct and unique in comparison to the triumphal arches of Rome. This arch is four-sided and acts as a gateway into the city. Corinthian columns, eight in total, stand at each corner and support broken pediment, a common architectural feature in the North African and Eastern provinces. Despite its very different design, the arch's components are in dialogue with the triumphal arch in Rome. Depictions of war spoils and captive barbarians line the interior of the arches and a frieze wraps around them, depicting the triumphal procession that occurred in Rome. This frieze is both a portrayal of the actual triumph that Septimius Severus enjoyed as well as a mythical presentation, as gods and personifications are also present in the procession and at the sacrifice that followed.

Arch of Septimius Severus

Leptis Magna, Libya.

Most importantly, the arch at Leptis Magnus demonstrates the emerging artistic style of the second century CE and Late Antiquity. The figures in the frieze are squat and square. The limbs are thick, and their clothing is stylistically rendered with incised lines that give no indication of the body underneath. It is a complete displacement of the Classical style that dominated Roman art during the previous three centuries

Baths of Caracalla

Caracalla was one of the last emperors of the century who had the time, resources, and power to build in the city of Rome.

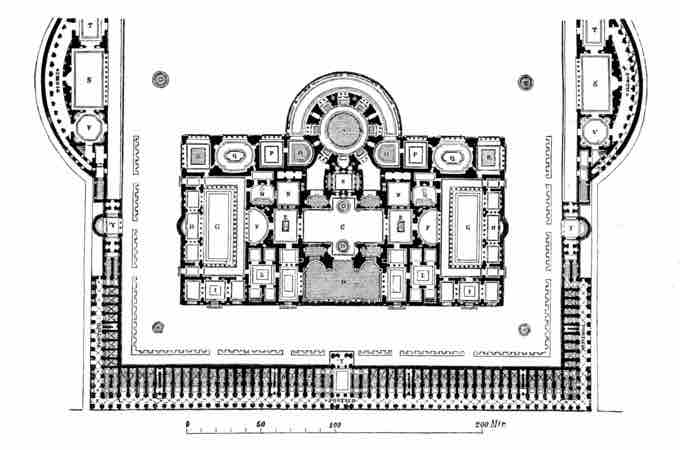

His longest-lasting contribution is a large bath complex that stands to the southeast of Rome's centre. It covered over 33 acres and could hold over 1,600 bathers at a time. Bathing was an important part of Roman daily life, and the baths were a place for leisure, business, socializing, exercising, learning, and illicit affairs. These baths not only held the traditional bathing pools but also exercise courts, changing rooms, and Greek and Latin libraries. A mithraeum has also been found on the site.

Baths of Caracalla

Reconstructed ground plan of this vast complex.

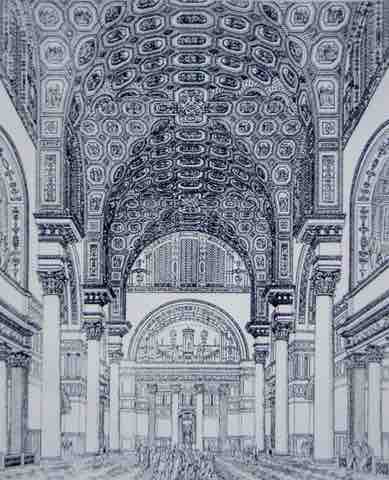

Architecturally, the Baths of Caracalla demonstrate the impressive mastery of Roman building and the importance of concrete and the vaulting systems developed by the Romans to create large and impressive buildings with ceilings spanning great distances. The building was lavishly decorated with marble veneer, fanciful mosaics, and monumental Greek marble statues.

Baths of Caracalla, reconstruction of interior.

This artist’s reconstruction shows a groin-vaulted interior, Composite columns, and decorative panels on the ceiling. Human figures have been added for scale.

Quirinal Hill Serapeum

In 212, Caracalla erected a temple (called a Serapeum) on Quirinal Hill dedicated to the Egyptian god Serapis, a human-headed deity that shared Greek and Egyptian attributes. This Serapeum was, by most surviving accounts, the most sumptuous and architectonically ambitious of those built on the hill. The temple covered over three acres. It was composed by a long courtyard (surrounded by a colonnade) and by the ritual area, where statues and obelisks had been erected. Designed to impress its visitors, the temple boasted columns nearly 70 feet tall and over six feet in diameter, visually sitting atop a marble stairway that connected the base of the hill to the sanctuary. The ruins of the Serapeum show a mixture of brick and concrete with regular use of the round arch. Symbolically, the temple signified the diversity that the Roman pantheon had reached by the third century.

Ruins of Caracalla’s Serapeum on the Quirinal Hill.

Rome, Italy. 212 CE.