In 509 BCE, the Etruscan kings of Rome were expelled from the city, and the Roman Republic was established. By the fourth century BCE, Rome was beginning to expand across the Italian peninsula, and the first Etruscan city to fall was Veii in 396 BCE. Over the following centuries, Etruria was involved in Roman wars, and Etruscan territory was fully conquered by the Romans by the beginning of the first century BCE. While Roman culture drew from its Etruscan roots, borrowing and adapting Etruscan customs, Etruscan society was also influenced by Roman culture. During this period, art begin to adopt a Roman style and display the permeation of Roman culture and values into Etruscan society. The threat of invasion also led to the common presence of violence, especially in funerary images.

Funerary Art and Sarcophagi

Funerary art, both in tomb paintings and on carved sarcophagi, underwent a noticeable change in subject matter during the Roman period. The figures of Charun and Vanth, demons of the underworld, were depicted with increasing regularity. Both figures are often depicted with wings, while Charun is often depicted with blue skin to signify putrefying flesh. They also carry torches, used to light the way to the underworld, or sometimes keys to open the door to the underworld, which underline the figures' role as guides between the world of the living and the world of the dead. In tomb paintings in Tarquinia, figures of Charun and Vanth can be seen painted in front of or around doorways.

Charun and Vanth

Charun guards the gate to the Underworld, while Vanth guides the deceased to the gate. Fresco. Third century BCE. Tomb 5636, Monterozzi Necropolis, Tarquinia, Italy.

While Charun's name is likely a derivative of the Greek underworld ferryman Charon, Vanth appears to be uniquely Etruscan. Due to Charun's menacing associations, theories have attempted to associate Vanth with the avenging Greek Furies. However, her role as a benevolent guide conflicts with this suggestion. Regardless of Vanth's exact role and origins, the appearance of a less than joyous afterlife and menacing figures in Etruscan funerary art does not emerge until after the beginning of the Roman incursions into Etruscan territory. Perhaps Vanth is a gentler apotropaic figure, offering the reassurance of an ally in the afterlife to counteract the trials faced in the face of impending cultural collapse and absorption.

Charun and Vanth also appear on stone and terra cotta sarcophagi. Charun is also sometimes depicted with a hammer. On the Sarcophagus of Lars Pulena, two figures of Charun (with hammers but without wings) are depicted on either side of a central figure, most likely Lars Pulena, swinging their hammers at his head. The violent image might have been used as an apotropaic device to ward off evil. However, in comparison to earlier funerary images, the level of violence seems to mimic the new level of violence in Etruscan society from Roman forces and influence. Two winged representations of Vanth also appear on the sarcophagus, at either end of the frieze.

The lid of the sarcophagus depicts a portrait of the deceased. The man lies alone, wearing a somber expression, unlike the earlier terra cotta Sacophagus of the Spouses. His face is wrinkled and reflects a Roman republican portrait style, which equates age with wisdom and leadership capabilities. He has a pot belly, signifying his wealth, good life, and robust eating, and he holds a scroll across his lap that is inscribed with a list of his accomplishments.

Sarcophagus of Lars Pulena

With figures of Charon and Vanth on the frieze. Tufa. Early second century BCE. Tarquinia, Italy.

Smaller cinerary urns assumed the shapes of sarcophagi during this period. These urns are topped with images of the deceased lying across the lid, often in Roman dress, with relief-carved scenes of battle, violence, or Charun and Vanth. The woman who reclines atop the urn wears attire more akin to that of a Roman matron than to the woman on the Sarcophagus of the Spouses. Unlike the Etruscans, who buried their dead in tombs designed to mimic the appearance and comforts of private homes, the Romans practiced cremation and stored the ashes of their deceased in cinerary urns. This shift in Etruscan culture demonstrates the adoption of Roman funerary practices.

Cinerary Urn

Cinerary Urn for a woman with apotropaic imagery. Terra cotta. Mid-second century BCE.

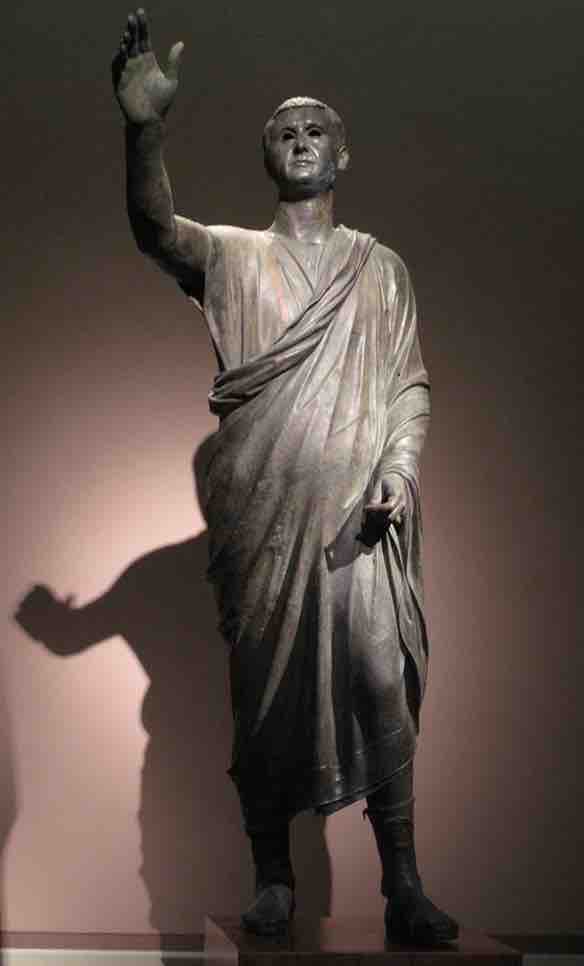

Aule Metele

Aule Metele, also known as The Orator, is a life-size bronze sculpture of an Etrusco-Roman man. The figure is depicted wearing a Roman toga and Roman sandals. He stands in a pose of an orator, with his hand raised to address a crowd. To further emphasize this gesture, the hand is slightly enlarged. He is clearly depicted as an individual, and an inscription on the hem of his toga in Etruscan names him as Aule Metele. Aule Metele dresses as a Roman magistrate, and his face is a cross between Hellenistic and Roman veristic portraiture. The sculpture shows a level of individuality through the gaunt cheeks, thin lips, and wrinkled forehead. As with the sculpture on the Sarcophagus of Lars Pulena, these attributes of age align with the respect afforded to elders in Roman society. While the inscription marks him as an Etruscan, his attire and pose demonstrate the absorption of Roman culture into Etruscan society and the adoption -- especially by the ruling class of Etruscans -- of Roman civic practices.

Aule Metele

Bronze. First century BCE. Cortona, Italy.

Late Temple Sculpture

By the second century BCE, at least two Etruscan temples began to show evidence of the absorption of the Roman culture. Unlike early temples, whose pediments were largely unadorned, temples in the cities of Luna and Talamone incorporated pedimental sculptures in the style of the Greeks. Although Roman pediments remained free of sculpture groups, Roman influence is clearly visible in these terra cotta figures. Whereas pre-Roman temple sculptures were largely stylized like the Apulu of Veii, the pedimental figures from the temples at Luna and Talamone possess the naturalism of Classical and Hellenistic sculpture, both of which were adopted by the Romans. Unlike Greek pedimental sculpture that depicted male nudes, the figures from the pediment from Talamone, which depicts the fate of the Seven against Thebes, wear Roman battle gear, including short-sleeved skirted armor. By the time the sculpture groups from both temples were produced, their cities were under Roman control.

Pedimental fragments from the Temple of Luna.

Terra cotta. 175-150 BCE. Luni, Italy.

Pediment from the Temple of Talamone

Terra cotta. Second century BCE. Grosseto, Italy. The first closed pediment in Etruria, this sculpture group depicts the fate of the Seven against Thebes.