Overview: The Spanish Conquest and the Fall of the Inca

The Spanish Conquest of the Inca Empire was catastrophic to the Inca people and culture. The Inca population suffered a dramatic and quick decline following contact with the Europeans. This decline was largely due to illness and disease such as smallpox, which is thought to have been introduced by colonists and conquistadors. It is estimated that parts of the empire, notably the Central Andes, suffered a population decline amounting to a staggering 93% of the pre-Columbian population by 1591.

As an effect of this conquest, many aspects of Inca culture were systematically destroyed or irrevocably changed. In addition to disease and population decline, a large portion of the Inca population—including artisans and crafts people—was enslaved and forced to work in the gold and silver mines. Cities and towns were pillaged, along with a vast amount of traditional artwork, craft, and architecture, and new buildings and cities were built by the Spanish on top of Inca foundations.

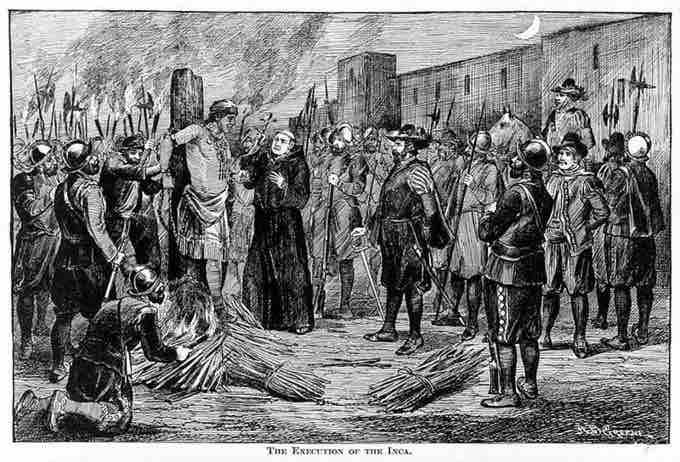

The execution of the Inca

Spaniards burning the Inca leader Atahualpa at the stake, following their conquest of the Inca people.

The Role of Christianity

Beginning at the time of conquest, art of the central Andes region began to change as new techniques were introduced by the Spanish invaders, such as oil paintings on canvas. The spread of Christianity had a great influence on both the Inca people and their artwork as well. As Pizarro and the Spanish colonized the continent and brought it under their control, they forcefully converted many to Christianity, and it wasn't long before the entire region was under Christian influence. As a result, early art from the colonial period began to show influences of both Christianity and Inca religious themes, and traditional Inca styles of artwork were adopted and altered by the Spanish to incorporate Christian themes.

Spanish Architecture

Pizarro, the Spanish explorer and conquistador who was responsible for destroying much of the city of Cusco in 1535, built a new European-style city over pre-colonial foundations. For instance, the Convent of Santo Domingo was built over the Coricancha ("Golden Temple" or "Temple of the Sun," named for the gold plates covering its walls), which had been the most important sanctuary dedicated to the Inti (the Sun God) during the Inca Empire. The Convent was built in the Renaissance style and exceeds the height of many other buildings in the city.

The Convent and Church of la Mercad was similarly modeled on the Baroque Renaissance style, containing choir stalls, paintings, and wood carvings from the colonial era. The Cathedral of Santo Domingo was built on the foundations of the Inca Palace of Viracocha and presents late-Gothic, Baroque, and Plateresque interiors; it also has a strong example of colonial goldwork and wood carving. La Iglesia de la Compaña de Jesus was later constructed by the Jesuits over the foundations of the palace of the Inca ruler Huayna Capac, and is considered one of the best examples of the colonial baroque style in the Americas. Its façade is carved in stone, and its main altar is made of carved wood covered with gold leaf.

European-Style Art

The majority of artistic efforts after the initial conquest were directed at evangelism; a number of schools of painting emerged which exemplify this. Indigenous artists were taught European techniques but retained styles that were representative of their local sensibilities. During the 1700s and early 1800s, the Spanish Baroque aesthetic was transplanted to central and South America and became especially influential, developing its own variations in different regions.

The Cusco School

The Cusco School was a Roman Catholic art movement that began in Cusco, Peru during the early colonial period. Initially developed by the Spanish to train local artists in the European tradition for the purpose of proselytizing, the style soon spread through Latin America to places as distant as the Andes, as well as to the places in present-day Bolivia and Ecuador. Cusco is considered to be the first location where the Spanish systematically taught European artistic techniques such as oil painting and perspective to Indigenous people in the Americas. Bishop Manuel de Lollinedo y Angulo, a collector of European art, was a major patron of the Cusco School and acted as a patron to such prominent artists as Basilio Santa Cruz Puma Callao, Antonio Sinchi Roca Inka, and Marcos Rivera. Cusco painting is characterized by exclusively religious subject matter; warped perspective; frequent use of the colors red, yellow, and earth tones; and an abundance of gold leaf. Artists often adapted the subject matter of paintings to include native flora and fauna. Most of the paintings were completed anonymously, a result of Pre-Columbian traditions that viewed art as a communal undertaking.

Example of Cusco painting

Cusco painting is characterized by exclusively religious subject matter; warped perspective; frequent use of the colors red, yellow, and earth tones; and an abundance of gold leaf.

The Quito School

The Quito School (Escuela Quitena) developed in the territory of the Royal Audience of Quito during the colonial period. The artistic production of this period was an important means of income for the area at the time. The Quito school was founded in 1552 by the Franciscan priest Jodoco Ricke, who transformed a seminary into an art school to train the first artists. The work of this period represents a long process of mixed-heritage blending of indigenous people and Europeans, both culturally and genetically.

Quito School art works are known for their combination of European and Indigenous stylistic features, including Baroque, Flemish, Rococo, and Neoclassical elements. The technique of encarnado, or the simulation of the color of human flesh, was used on sculptures to make them appear more realistic. Another unique characteristic of the style was the application of aguada, or watercolor paint, on top of gold leaf or silver paint, giving it a unique metallic sheen. The racial blending of the time is reflected aesthetically in Quito school art works in figures with mixed European and Indigenous traits, both in features and clothing. Artists included local plants and animals instead of traditional European foliage, and scenes were located in the Andean countryside and cities.

Example of 'Encarnado' Sculpture

The technique of encarnado, or the simulation of the color of human flesh, was used on sculptures to make them appear more realistic.

The Chilote School

The Chilote School of religious imagery is another artistic manifestation developed during the colonial period by Jesuit missionaries with the purpose of evangelizing. The works of this style or movement reflect the aesthetics of blending typical of other schools in the Americas from this era. Examples of this again include the combination of European, Latin American, and Indigenous features, as well as local flora, fauna, and landscape.