Although it originated in Britain in the late 1950s, Pop Art did not gain momentum in America until a full decade later. By this time, American advertising had adopted many elements and inflections of modern art and functioned at a very sophisticated level. Consequently, American artists had to search deeper for dramatic styles that would distance fine art from more well-designed and clever commercial materials. Pop Art presented a challenge to traditions of fine art by including aspects of mass culture, such as advertising, comic books, and mundane, cultural objects. One of the goals of Pop Art was to blur and draw into question the boundaries between "high" and "low" art or popular culture.

Neo-Dada

Two important painters in the establishment of America's Pop Art vocabulary were the American Neo-Dadaists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. In the mid-1950s, Jasper Johns began to appropriate popular abstract iconography for painting, thus allowing for a set of familiar associations to answer the need for a subject. In contrast to the Abstract Expressionists, who not only disdained subject matter but also took their paintings to be an index of the artist's presence on the canvas, Neo-Dadaists sought to create meaning solely through the use of conventional symbols and icons such as targets, flags, letters and numbers. These neutral subjects rejected a reliance on the hand of the artist in the production of meaning-- the surface of the painting could declare itself without reference to the persona that created it. Robert Rauschenberg also was considered a Neo-Dadaist, and his "Combines" incorporated found objects, printed materials, and urban debris with traditional fine art materials. Combines served as instances in which the delineated boundaries between art, sculpture, and the everyday object were broken down so that all were re-contextualized in a single work of art.

Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954-55, Encaustic, oil, collage on fabric mounted on plywood, 42 x 61 in. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Flag by Jasper Johns presents the American flag as subject matter, thus invoking a plethora of associations and juxtapositions between the popular image, symbol, and fine art.

Roy Lichtenstein

Of equal importance to American Pop Art is Roy Lichtenstein. His work defines the basic premise of Pop Art better than any other through parody. Selecting the old-fashioned comic strip as subject matter, Lichtenstein produced hard-edged, precise compositions that documented mass culture while simultaneously creating parodies of it in a soft manner. Lichtenstein used oil and Magna paint in his best known works, such as Drowning Girl (1963) , which was appropriated from the lead story in DC Comics' Secret Hearts #83. His characteristic style featured thick outlines, bold colors and Ben-Day dots to represent certain colors, as if created by photographic reproduction. Lichtenstein's contribution to Pop Art merged popular and mass culture with the techniques of fine art, while injecting humor, irony, and recognizable imagery and content into the final product. The paintings of Lichtenstein, like the works of many other pop artists, shared a direct attachment to the commonplace image of American popular culture, while treating the subject matter in a cool, impersonal manner. This detached manner illustrated the idealization of mass production and its inherent anonymity.

Roy Lichtenstein, Drowning Girl, 1963, MOMA

Lichtenstein calls into question notions of appropriation while simultaneously blurring the lines between high and low art in this painting of a scene from a popular comic book.

Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol is probably the most famous figure in Pop Art. Warhol attempted to take Pop beyond an artistic style to a life style, and his work often displays a lack of human affectation that dispenses with the irony and parody of many of his peers. Warhol's artwork ranges in many forms of media including hand drawing, painting, printmaking, photography, silk screening, sculpture, film, and music. His studio, The Factory, was a famous gathering place that brought together distinguished intellectuals, drag queens, playwrights, Bohemian street people, Hollywood celebrities, and wealthy patrons. New York's Museum of Modern Art hosted a Symposium on Pop Art in December 1962 during which artists like Warhol were attacked for "capitulating" to consumerism. Critics were scandalized by Warhol's open embrace of market culture. This symposium set the tone for Warhol's reception. Throughout the decade it became increasingly clear that there had been a profound change in the culture of the art world, and that Warhol was at the center of that shift. In the early 60s Warhol pared his image vocabulary down to the icon itself--brand names, celebrities, dollar signs-- and removed all traces of the artist's hand in the production of his work . Eventually, he moved from hand painting to silk-screen printing, removing the handmade element altogether. The element of detachment reached such an extent at the height of Warhol's fame that he had several assistants producing his silk-screen multiples.

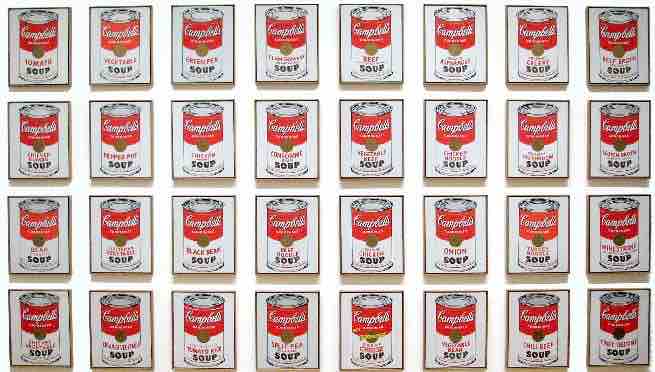

Andy Warhol, Campbell's Soup Cans, 1962, synthetic polymer on 32 canvases. 20 x 16 in each. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Warhol's Campbell's Soup Cans have become synonymous with the Pop Art movement and exemplify his preoccupation with notions of pop culture and capitalism.

The legacy of Pop Art is expansive, and much of the Pop art of the 1960s is considered incongruent, as many different conceptual practices fed into the movement and are reflected by a wide variety of artists. The list of notable Pop artists is extensive, but some major proponents include Jim Dine, Richard Hamilton, Keith Harin, David Hockney, Alex Katz, Yayoi Kusama, John McHale, Claes Oldenburg, Julia Opie, Eduardo Paolozzi, Sigmar Polke, Ed Ruscha, George Segal, and Tom Wesselman.