History of Photography

The history of photography has roots in antiquity with the discovery of the principle of the camera obscura, and the observation that some substances are visibly altered by exposure to light. Thomas Wedgwood is generally accepted to have made the first reliably documented although unsuccessful attempt. In the mid-1820s, Nicéphore Niépce succeeded, but several days of exposure in the camera were required and the earliest results were very crude. Niépce's associate Louis Daguerre went on to develop the daguerreotype process, the first publicly announced photographic process, which required only minutes of exposure in the camera and produced clear, finely detailed results. It was commercially introduced in 1839, a date generally accepted as the birth year of practical photography.

Throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s a number of competing processes were experimented with and distributed to the public in varying degrees. The demand for portraiture that emerged from the middle classes during the Industrial Revolution could not be met in volume and in cost by oil painting, a factor which added to the push for the development of photography. Eventually, the Daguerreotype emerged as the most popular and affordable method for the general public, however, daguerreotypes were fragile and difficult to copy, and lacked portability as they required plates and toxic chemicals to be carried around. In 1884 George Eastman, of Rochester, New York, developed dry gel on paper, or film, to replace the photographic plate so that a photographer no longer needed to carry boxes of plates and toxic chemicals around. In July 1888 Eastman's Kodak camera went on the market with the slogan "You press the button, we do the rest". Now anyone could take a photograph and leave the complex parts of the process to others, and photography became available for the mass-market in 1901 with the introduction of the Kodak Brownie.

Photography as Art

Successful attempts to make fine art photography can be traced to Victorian era practitioners such as Julia Margaret Cameron, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, and Oscar Gustave Rejlander and others. In the U.S., F. Holland Day, Ansel Adams, Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen were instrumental in making photography a fine art, and Stieglitz was especially notable in introducing it into museum collections. Until the late 1970s several genres predominated, such as nudes, portraits and natural landscapes. Breakthrough artists in the 1970s and 80s, such as Sally Mann, Robert Mapplethorpe, Robert Farber, and Cindy Sherman, still relied heavily on such genres, although seeing them with fresh eyes. Others investigated a snapshot aesthetic approach. American organizations, such as the Aperture Foundation and the Museum of Modern Art, have done much to keep photography at the forefront of the fine arts.

Photo-Secession Movement

Photographer Alfred Steiglitz (1864–1946) led the Photo-Secession movement, a movement that promoted photography as a fine art and sought to raise standards and awareness of art photography. The Photo-Secession movement placed the focus on the role of the photographer as an artist. It was characterized by pictorialism, in which pictures and photographic materials were manipulated to emulate the quality of paintings and etchings being produced at that time. Among the methods used were soft focus; special filters and lens coatings; burning, dodging and/or cropping in the darkroom to edit the content of the image; and alternative printing processes such as sepia toning, carbon printing, platinum printing or gum bichromate processing. Centered in Gallery 291 in New York City from 1902-1916, membership to the Photo-Secession movement was by invitation-only and varied according to Stieglitz's interests. The most prominent members included Edward Steichen, Clarence H. White, Käsebier, Frank Eugene, F. Holland Day, and Alvin Langdon Coburn.

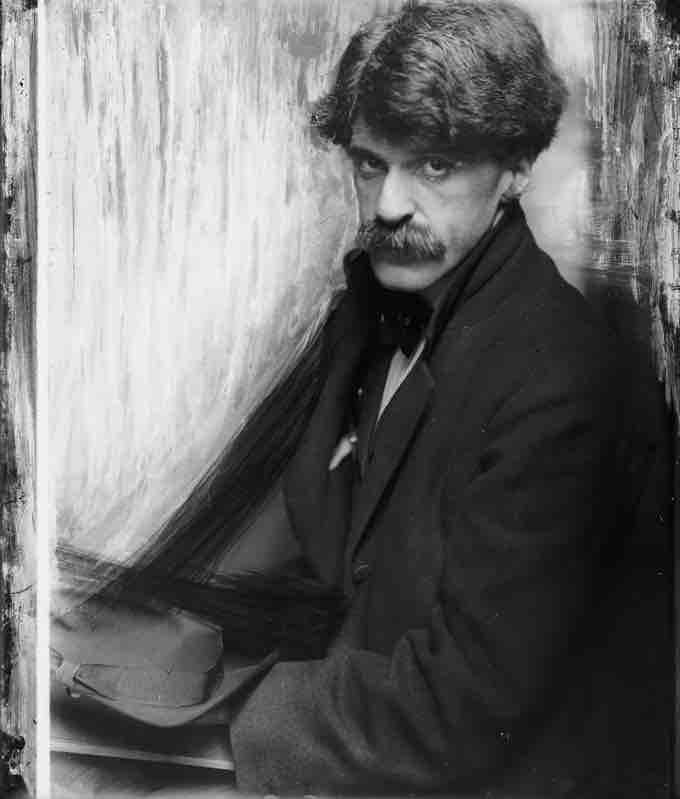

Gertrude Kasebier, Alfred Stieglitz in 1902

Gertrude Kasebier, Alfred Stieglitz in 1902.

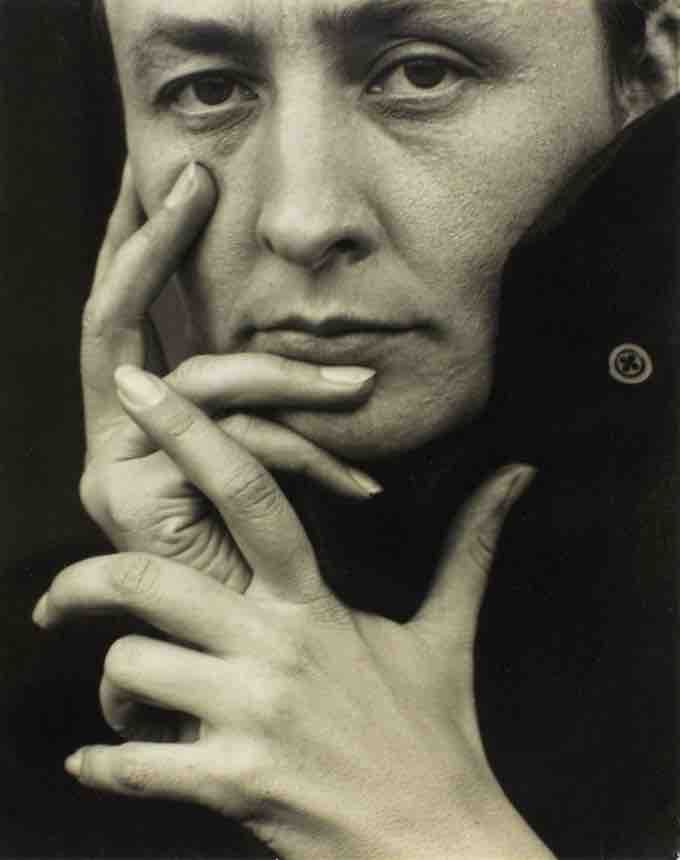

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe, Hands

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe, Hands, 1918.

At the same time, however, photography's use as a tool of realistic documentation mirrored the growth of American Realism in art and sculpture. Many photographers sought to capture everyday life of American people - both the wealthy and the poor - in a realistic and often gritty fashion. Lewis Hine (1874 - 1940) used light to illuminate the dark areas of social existence in his Pittsburgh Survey (1907), which investigated working and living conditions in Pittsburgh. He later became the photographer for the National Child Labor Committee. Paul Strand (1890 - 1976) created brutally direct abstractions, close-up portraits, and documented machines and cityscapes.

Precisionist Movement

Edward Weston (1886 - 1958) would become a leader in the Precisionist Movement, a style that functioned in direct opposition to the Photo-Secession Movement. This movement was the first true use of modernism in photography. It was characterized by sharp focus and carefully framed images. James Van Der Zee (1886 - 1983) was an African American photographer who became emblematic of the Harlem Renaissance movement. He was best known for his portraits of black New Yorkers and produced the most comprehensive documentation of the period.

Commercial Photography

Commercial photography also expanded during this time, as in the works of Edward Steichen (1879 - 1973). Steichen broke with Stieglitz toward the end of the Photo-Secession movement and created the first commercial image in 1919, entitled Pear and Apple. His work was featured in magazines such as Vanity Fair. Ansel Adams (1902 - 1984) also began his career as a commercial photographer and became widely known for his images of American landscapes.

Ansel Adams, The Tetons and the Snake River, 1942

A typical Ansel Adams photograph featuring the American landscape in black and white.